I’ve had in my head for some time a general theory of society, that I’ve been meaning to put down in writing. Here goes:

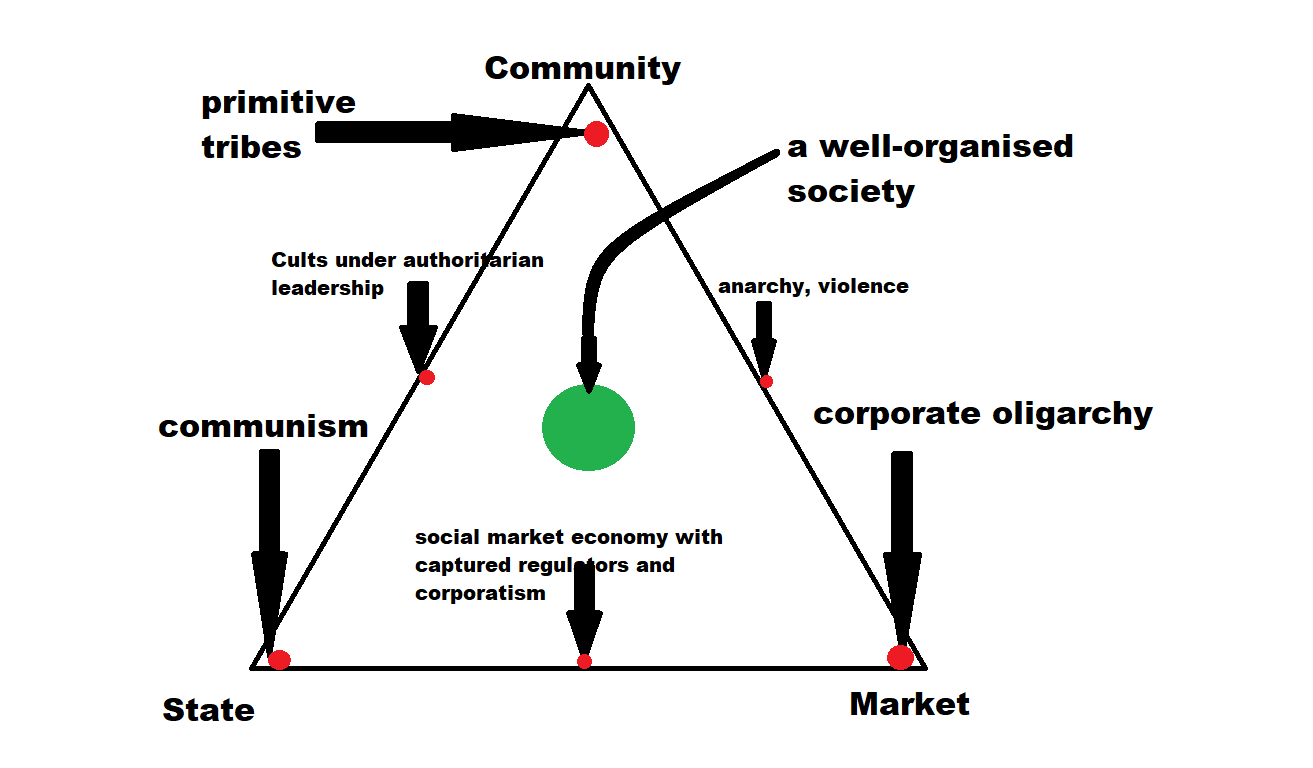

Society – any society – consists of three essential elements: a State, a Market and a Community. Let’s take each in turn.

The State is, in its essence, the monopoly on physical force. The weaker the State is in a given society, the more physical force is dispersed between different actors. The stronger the State, the more physical force is concentrated in the State itself. A hallmark of a strong State is, therefore, laws which prohibit any form of violence, up to and even including self-defense.

It follows from this definition of the State that everything it does in some way relates to its monopoly on violence. For example, the State spends money on infrastructure. But in order to do so, that money must come from taxes. These in turn are collected from taxpayers who, if they refuse to pay, will have the money taken from them. If they resist, the State will not hesitate to use physical force to compel them out of their possessions and into prison.

Next comes the Market. The Market is the free exchange of value between actors. It reposes on the assumption that exchange is mutually beneficial. In its purest form, the Market knows neither altruism nor compulsion. Each actor enters the Market to further his own self-interest, and finds that agreement with other actors is the best way of doing this.

The final pillar of society is Community. Community is all voluntary interactions of social actors that are neither transactional nor subject to compulsion under threat of physical force, So anything that is non-State or non-Market is by definition Community. Examples of Community are families, friendships, bowling clubs, religions and board game meetups.

A key feature of Community is that it has the power of banishment or exclusion, but no other power. Another key feature is that interactions within a Community tend to be highly altruistic. Community members ‘care’ about one another, and in fact are often willing to suspend their own self-interest in pursuit of Community-defined goals and in adherence to Community-defined values.

Now comes my core hypothesis about the ideal organisation of a society:

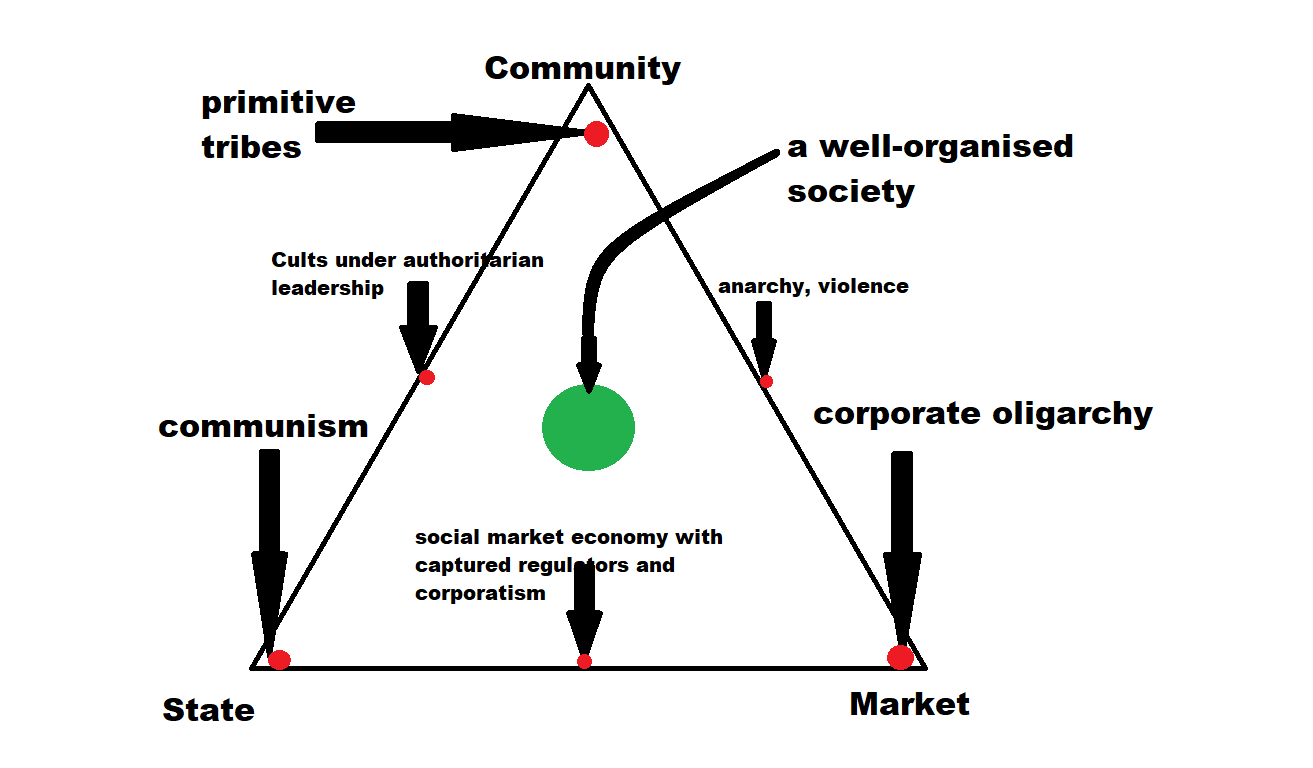

A society can be said to be well-organised when the Community, the Market and the State all have equal weight. This is because each of these three mechanisms represents an important check on the other two. The State provides order and peace, the Community provides values and morals, and the Market provides economic rationality and innovation.

A society that has a strong State, but a weak Market and a weak Community, will tend towards Communism. The lack of (Community) moral compass will allow the State’s leadership to abuse its monopoly on power, while the lack of (Market) pressure will lead to bad economic-decision making and undermining of democracy, because consumers and businesses exert a democratising influence.

A society with a strong Market, but a weak State and a weak Community, will tend towards Corporatism, a consolidation of economic power in the hands of wealthy oligarchy, who will lack morals (e.g. fly to space with Captain Kirk in a giant dick, while their workers have to pee in bottles). Likewise, enforcement of contracts will be impossible, because that requires either the compulsion of the State or the moral impetus of the Community. Ultimately, even basic transactions will be burdened with additional costs of self-enforcement, and entire markets will collapse under that cost.

It’s rather hard to find examples of a society characterised by strong Community, but weak State and a weak Market. However, tribal societies exactly fitted this description. And while they may be marked by a degree of stability, I would argue that this comes at a high price: investment is next to impossible, nothing is there to drive human progress and innovation.

In modern political discourse it is conventional to consider society along a ‘left-right’ axis, in which two of the three essential societal elements are considered as opposing poles of a spectrum. My hypothesis suggests that in fact there is no place along this spectrum that can deliver a healthy, well-functioning society, because the third element – Community – is not represented.

That is why it is best to illustrate politics not with a left-right spectrum, but with a Social Triangle

And in fact, much of the imbalance in modern society is related to a steady erosion of the influence of Community on our daily lives. Church attendance has plummeted, people have fewer meaningful friendships and participate in fewer activities. Families are smaller and more fragmented than ever before. Indeed, we have drifted down the Social Triangle, and are approacing the bottom axis that runs between State and Market.

That is why when the Left and the Right complain about the other side, they are both right and both wrong. A good example is around Hate Speech. New laws are being rushed upon us by well-meaning, but wrong-headed Leftists to outlaw saying ‘mean things’. These laws are incredibly stupid – at best they won’t work, and at worst they will. But the question is, why is this happening? Simply put, the power of the Community to check the behaviour of society’s members is increasingly absent. We now find ourselves trying to criminalise the sort of behaviour that used to cost you friendships, club memberships and a place at your cousin’s dinner table.

Markets are also malfunctioning in ways that Right-wingers find hard to explain away. It turns out that excessive greed and amorality are themselves a form of market failure, because any asymmetry between market participants creates an opportunity for sharp practice – information is imperfect, bargaining power is lopsided. Absent Community, the only way to check those immoral excesses is ever-more costly regulation. That in turn creates opportunities for regulatory capture and barriers to entry for new market participants. We find ourselves in a social market economy that is neither very social nor very market.

What is the solution? Clearly, it is to restore some sense of Community – common values, a common purpose, a clear set of religious dogma and a shared moral code. Adam Smith understood the importance of this intuitively, (even if Karl Marx was less perspicacious in this regard).

Now, this is all well and good, but do I have any more practical suggestions or is this just another ‘everything is awful’ blogpost? Here’s my three step plan:

- Awareness. Stop pretending like our Community doesn’t matter. Restart a conversation about what our values are, what we can agree on, and how we can come together to pray and play – knowing that is every bit as important as who our State leaders are or how our economy is working.

- Subsidiarity. An interesting result that comes out of the social triangle is the question of scale. It turns out the Market works ever better at scale, and the State too seems pretty able to work at scale. But Communities don’t seem to work very well at scale at all. Insofar as altruism is a key ingredient, it’s really not possible to have empathy with a million other people, much less 8 billion. In other words, today’s society is too big for real Community to exist. Not only is globalism a terrible idea, in fact, we need to break nations down into pieces that are well proportioned for Community to prosper. This suggests devolving more of the Market and the State to smaller scales – local government and buy local goods.

- Stop uncontrolled immigration. Yes, there I said it. Immigration is very bad for Community, for the obvious reason that immigrants are least likely to share the common values that bind people together in voluntary ways. Immigration erodes Community and splinters society.

- God. That’s right. The big guy. Flowing white beard. Turns out, not only is He almighty, but He’s also quite good for creating the conditions under which Communities can flourish. He sort of works as a rallying point and an anchor for common values and beliefs.

- Get the hell offline. I don’t believe the internet is the cause of failing Community. After all, the excellent book Bowling Alone came out when the internet was still in diapers. But I also don’t think the internet can be part of the solution. If you want real Community, you should get off this damn computer, go outside and meet people. Join a choir. Or a rugby team. Or take a pottery class.