Should old acquaintance be forgot…

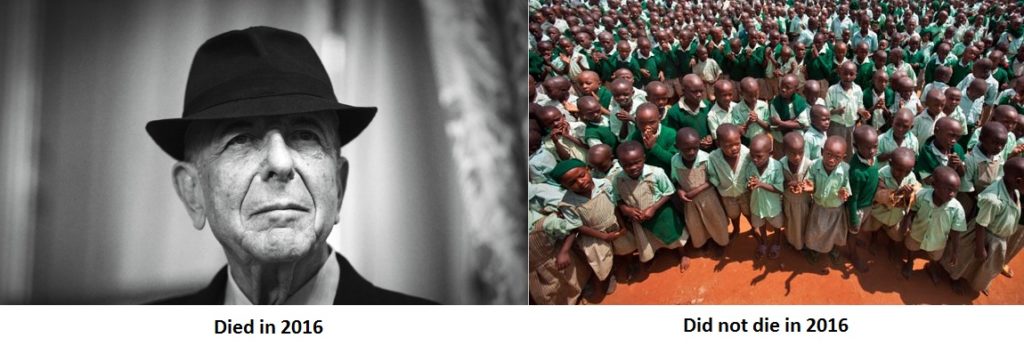

New Year’s for most of us has been more a question of ringing out the Old Year, rather than ringing in the New. It’s more or less universally accepted that 2016 has been a crummy one, at least within my circle of acquaintances. One particular feature has been the remarkable number of deaths, with George Michael and Carrie Fischer being but the last in a long list of casualties claimed by that angry teenager, Not-so-sweet ’16.

However, in actual fact, as a proportion of the total population, fewer people died in 2016 than in 2015. What’s more: as a percentage of the population, fewer people died in 2016 than in any year in the history of humankind. That’s right: In 2016, 0.76% of humans on earth kicked the bucket. By contrast, back in the ‘good ol’ days’ of say, 1960, that number was a whopping 1.77%. If you went back a Century, when the Great War was raging, it might have been closer to 3 or 4%. So in fact 2016 was the safest year ever to be a living human being.

This was thanks to lower infant mortality rates, better access to medicine, improved diets and – despite what has happened in Syria and a few other places – overall a reduction in violent death.

Adieu to the former artist formerly known as the Artist Formerly Known as Prince.

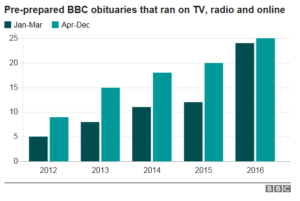

But the good news doesn’t seem to apply if you were a celebrity. The BBC has a good article which tracks obituaries for 2016 compared to previous years and yes, we’re not all just imagining it: The hard data backs up the commonly held opinion that 2016 has been a grim year for the rich and famous.

Which got me thinking about why we care so much. Why does it matter to us that someone – a singer or an actor – has passed away? Sure, they produced art which gave joy to our lives. But in almost all of these cases, the people in question were well past their artistic primes. And the art they gave us can still be enjoyed, even if they have now moved on to the Great Dressing Room in the Sky. Yet we seem to care, not just about their art, but about them, as people.

Which on the face of it is very weird. It hardly needs saying, but these people are strangers to us. We don’t know them personally, they certainly don’t know us or even want to know us, and even if by some freak chance we found ourselves snowed in to an alpine cabin in the company of a selection of Hollywood A-listers, we would quickly discover that they have nothing in common with us. So instead of cursing 2016 for the handful of complete strangers it has taken away, why don’t we choose to raise a glass of New Year’s bubbly and thank 2016 for sparing our friends and family?

Thou shall have no other gods before me, except perhaps the Kardashians

Of course we are grateful for our loved ones. But the fact is, celebs do matter to us. They fulfil a need which appears to be very human, that is, the role of the idol. This is nothing new to our age. The desire of the masses to look up to quasi-real demi-gods and follow their every movements is as old as mankind itself. Is our fascination with Angelina Jolie’s shocking decision to divorce Brad Pitt not the same kind as what the ancient Greeks must have felt about the decision by the mythological Jason, leader of the Argonauts, to divorce the powerful Witch-Princess Medea of Colchis, in order to tie the knot with the Corinthian princess Glauce? Did the plebs of Ancient Rome look upon Cleopatra any differently to the way the plebs of New York saw Marilyn Monroe? And the Hollywood Walk of Fame, can it not be seen upon the walls of any Catholic church, in the form of a star-studded line-up of Academy Award-winning saints?

In a sense, it is the decline in religion which has left a void in us; a void we seek to fill through celebrity culture. The image of callipygous Freya, the most beautiful female form imaginable, riding in a chariot pulled by two great cats through the Norse woods, together with her omnipotent husband Odin, is lost to us. But in its place we have bootylicious Kim and her theomaniac husband Kanye, riding in a sleek SUV along the highways of Los Angeles.

There’s one degree of separation between me and you: Kevin Bacon

And yet, while celebrity idolatry may always have served the purpose of setting a distant horizon to our plebeian ambitions, it seems that in recent years, the phenomenon has grown even more pervasive . I speculate that this is because, as cities become more vast and anonymous, and society more fragmented, we feel an ever larger yearning within ourselves to have something that connects us. With greater labour mobility and smaller families, more and more of us are moving about, lonely and disconnected. Shared references and common history are scarce, lost in the back of a rented U-Haul truck. Yet celebrities can restore that bond. We all know these beautiful super-humans from our one common altar – the TV screen. Taking an interest in their fate, becoming intimately acquainted with their ridiculously-named offspring and keeping track of their drug addictions and failed marriages becomes a vital source of shared reference. In the cold urban jungle, it is a comfort to me to think that while I may not know my neighbours, at least I know that they are watching the Oscars too. These saintly figures who float down the red carpets, in a mythological universe that seems planets away; they are the one true bond between us plebs.