An age of Twitter-fuelled ‘truthiness’

I have rarely felt so profoundly disappointed with the state of the rational world as I do these past few weeks. Perhaps it was my own cognitive dissonance at play, but if you had asked me a few short months ago, I would have rated our level of collective rationality as – overall – pretty high. Boy, was I wrong.

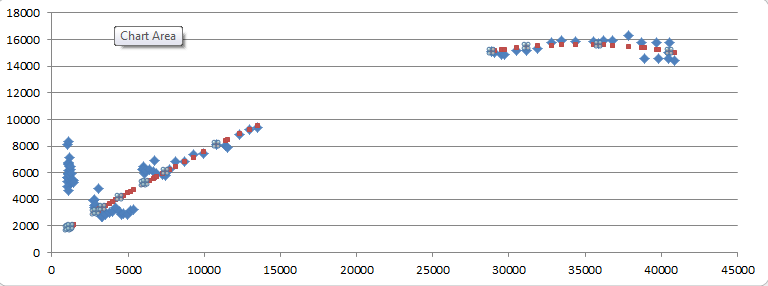

In fact, we live in a world in which the principles of scientific observation are disregarded, or else regarded selectively, in such a way as to concur with our collective feelings; in this case, collective hysteria. It is, as someone I know once put it, the essence of ‘policy-based evidence-making’. The clearest and most horrible example is the widespread use of the ‘number of cases’ statistic in the context of the COVID flare-up that struck in March/April (and has since gone away from almost all parts of the world). You won’t see a news report these days that doesn’t quote the ‘number of cases’, despite all honest epidimologists knowing the case count is a meaningless number: It tells you a little bit about the level of testing and nothing at all about the infection rate, for the strikingly obvious reason that the denominator is completely unknown.

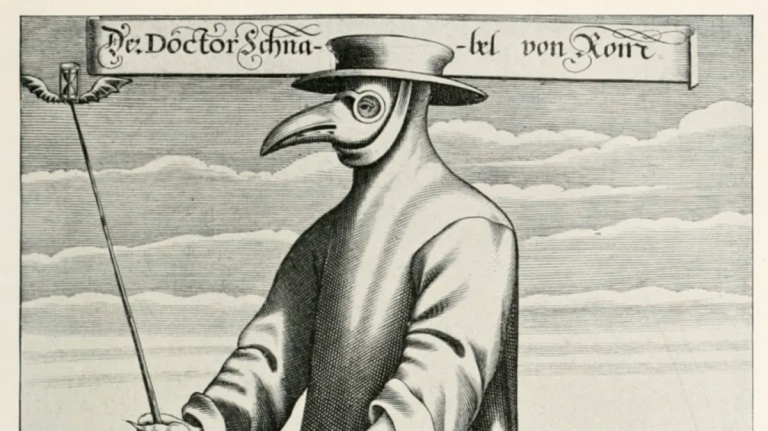

See no evil, hear no evil, spit no droplets of evil

Another good example is the use of face masks. They are more than just ubiquitous, they are fashionable. While in a shop yesterday, I took the opportunity to engage the mouthless young woman behind the til in conversation. Did her employer insist she wear one? No, came the muffled response from where her mouth should have been, but she chose to, because it made her feel better. “Although I don’t really know if it does anything,” she added, almost apologetically.

That’s of course fine. In a free society, anyone should have the right to adorn their bodies with whatever tin foil armour they believe might protect them from their chosen alien invaders. The problem is when the use of such adornments becomes compulsory thoughout the ‘free’ world, as is now the case on public transport, on flights, in indoor spaces, and even on public streets.

A narrative built on a meta-study built on a not-so-randomised control trail

Let’s be perfectly clear: there is no evidence that face masks protect against the spread of viral infections in the community setting. And I say this after having spent some time reviewing, line by line, the extant literature that has been recently quoted by proponents of the practice. What is shocking is how disingenious the pro-mask campaign can be.

One good example of how bad some of these studies are is to be found in one NYC radomised control trial from 2010, in which 450 households in a predominantly Latino neighbourhood were studied, divided into three control groups: Group one was given ‘education’ only about how to reduce infection. The second group was given ‘education plus hand sanitizer’. The third group was given ‘education plus hand sanitizer plus face masks’, with instructions that the head of household should wear one if anyone displayed symptoms, as well as children over 3 and ‘if possible’ the sick elderly person in the household.

The study reports the characteristics of the three groups, which despite ‘randomisation’ show clearly that the group which received face masks had different socio-economic characteristics: 50.8% of the face mask adults had high school diplomas or better, as against only 40.2% for the ‘education only’ control group. Then, though admitting that the face mask group never really used the face masks anyway, the authors proceed to conclude that the face masks are effective in reducing transmission of influenza.

This, in turn, is one of a number of studies quoted in the metastudies, such as the May 22 2020 Annals of Internal Medicine review, which in turn is used by media sources to support the public narrative. Even if these studies are cautious not to lie (the May 22 metastudy includes the rather unambiguous statement that “No direct evidence indicates that public mask wearing protects either the wearer or others.”), the authors know it’s the headlines that grab the public attention. And theirs is unambiguous in its messaging: “Cloth Masks May Prevent Transmission of COVID-19”. Again, not a lie, but it’s also true that pulverised moondust mixed with elephant tusk may cure cancer. No evidence, mind you, but it may.

Unmasking the cover-up

A question is why, if I can discover all this in a few days’ reading as a lay person, the medical, scientific and political establishment is so keen on pushing the face mask narrative? I posit a couple of possible answers.

First, a benign suggestion: The shock which COVID hysteria caused in society is best managed by allowing for a gradual return to normal. Like the masked salesgirl I refer to above, people actually feel better, more secure, with the masks. The argument then goes that we, as a society, should all mask up – at least for a while – to help the shellshocked return to public life without undue fear.

Now a more malignant thought: What if the political forces, including state-associated virologists and medical experts, now know that they massively overreacted to the outbreak of COVID-19? Maybe they have figured out, well ahead of the public, that the lockdowns were mostly ineffective (coming weeks if not months after they could have made any difference), and the infection fatality rate may in fact be as low as 0.05%. They also realise that they have wreaked untold harm on the economies and societies whose management was entrusted to them. Reputations, maybe even careers, are at stake. The game is now one of making ‘unlocking’ seem gradual, complicated, drawn out; because if they went back to normal too quickly, questions might be raised about why exactly we were forced to give up a third of our economy and two thirds of our civil liberties.