From the soundtrack for Papa Jack’s Café, the Musical. Written by Kylan Deghetaldi & Graham Stull

Author: Graham

Assisted Dying – my thoughts on the subject

The right to consume clickbaity outrage news on the internet, with peace and dignity

Some current affairs topics refuse to go away. They start as a minor irritation you scroll past in the online media. Then they develop into a more serious outbreak, covering the news in debilitating fashion. Every poorly informed article or overwrought tweet causes you throbbing, continuous pain, sucking the joy out of your daily doomscroll, until the only humane solution is to seek the sweet, peaceful relief of writing your own blog post on the topic. So it is with the debate on Assisted Dying (AD).

So here goes.

At the core of the question of whether or not there should be some legal framework for Assisted Dying is one of agency. Specifically, it prompts the question: What right does an individual have to exterminate his own live?

We hold these truths to be self-evident…

It has been commonly held in Western society that a rational individual should enjoy all and any freedoms which do not directly impinge on the freedoms of others – or as a pugilistically inclined fellow student at Trinity once put it, “the limit of one man’s fist is another’s face”. It follows from this that a rational individual who wishes to commit suicide should not be held back from jumping, provided it is done in a way that minimises collateral blood splatter.

But it is in the very word ‘rational’ that the rub lies. For implicit in our understanding of what is rational is an acceptance of the root desire a human – in common with all living things – must have to continue to live. It is taken as axiomatic that life, above all, craves its own continuance. We see it in every ant, every garden weed, every government agency. So the wisdom holds that he who would go against this most basic instinct has lost his mind, and therefore can no longer be presumed to enjoy the freedoms we allow to ‘rational’ individuals – it’s padded cells and happy pills for you, dear chap.

Don’t jump!…

This paternalism for the suicidal is not beyond criticism – at very least it should be clear that the policy is predicated on the assumption that a determined self-destroyer will always retain sufficient sovereignty to carry out the act, irrespective of the rules. We don’t so much prohibit suicide, as deny freedom to those who have engaged in clumsy attempts at self-harm. Still, the policy enjoys wide public support and a long tradition in almost all Western countries.

In this context, I can’t help but marvel at the incongruity between a system that would at once lock away one set of people for the sin of wanting to end their own lives, while at the same time creating the legal space, in some cases even taxpayer-funded, to provide the practical means for a different set of people to end theirs. A physically healthy 18 year old who tells her therapist she wants to kill herself can be committed to prevent self-harm; but if she waits forty years and can prove she has some chronic pain, the same doctors will stick the death serum in her arm.

…no wait, your life really sucks. Jump!

To square this circle, society must make some judgement of when and under which conditions the desire for suicide can be considered ‘rational’. If you have a healthy young body, you’d have to be crazy to want to destroy it. If you’re body is covered in wrinkles and riddled with cancer, you might just have a point. In other words, we must make an evaluation of what is the value of residual life.

Who precisely makes this evaluation and under which criteria? This is not a trivial question, neither in law nor in moral reasoning. Health economics has some tools to value life, notably the concept of a Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALYs), which are used to determine objective thresholds for the approval and administration of expensive treatments. But these are blunt tools. Using them to set solid benchmarks for AD is anything but straightforward. Even if it were possible to decide how much remaining life is enough to force someone to live it, the thornier question of how much suffering a person should be expected to endure during that period cannot be answered with statistical tools alone.

Nine out of ten doctors agree … with whatever pays their golf club membership dues

And so most AD regimes rely on the opinion of two medical experts, and some round concepts to do with ‘chronic pain’ or ‘terminal illness’ (being born is a terminal illness, but okay…) Here we are far from out of the woods – opponents of AD point to the risk of slippage, the arbitrary nature of medical opinion, and the influence greedy heirs or a cash-strapped healthcare system might put on an fragile, elderly patient who doesn’t “want to be a burden”. If we are killing impoverished, unemployed 45 year olds, depressed because they can’t pay their rent, how far have we come from the ‘peace and dignity’ the Death Serum Dispensers promised our beloved parents would be free to choose?

You can’t place a value on something unless you know what it is for

But the thing I find most interesting in the AD debate is not where or how this line is drawn, but rather what the line itself tells us about our society. The very act of valuing the quality of residual human life reveals something fundamental about what we see as the purpose of life itself.

In those distant times before social media, a majority of Westerners still did not consider that they had come to earth in order to seek happiness. Looking further back into the pre-history of the 20th Century and before, much of our Judaeo-Christian theology exhorts us to treat such indulgences as sinful. We are here, so the stoic reasoning goes, in order to suffer, to cleanse our spirits and prepare for a higher state of being in the next life. A painful exit from this world was a cleansing one; the peace ultimately achieved all the more divine.

But increasingly, it is hedonism that underpins our culture now. We live for no higher purpose than the pleasure of our own flesh. It follows that pain is abhorrent and must be avoided at all costs. As that flesh fails, and the possibility of pleasuring it recedes, there can be no reason for a hedonist to keep living. Of course, this is itself a pernicious death spiral, because hedonism is too shallow a philosophy to provide any meaningful fulfillment, especially for those who suffer the kinds of trauma that make superficial happiness appear elusive. This is why more and more young people are turning to depression, medication and ultimately, to the Assisted Dying solutions that, a decade ago, would have landed them in a mental hospital. No one is even inviting them to think about changing their world view from self-absorbed hedonism, to living a life in service of others.

I just want the Almighty to have the right to die with dignity

However, I remain an optimist. Contrary to Nietzsche’s assertions, rumours of God’s death are greatly exaggerated. He might be chronically pained to see the sorry state of our culture. It might even seem like He is terminally ill. But I’m not ready to sign off on His dose of death serum quite yet. So I’ll put my back behind stopping this Assisted Dying madness.

And I will remain a believer in life – the fun & quirky; the hard & ugly; the warts, the cancer cells and all.

Failure is just God’s way of telling you to try harder

When I think back over my life, I have few if any regrets for the things that I did. Even the very stupid decisions I have taken – like marrying a woman who raised more red flags than a Mao Zedong rally – have ultimately only led me to good or better life outcomes. I wouldn’t change them if I could.

But regrets I have. I regret every time I fell down, and didn’t get back up. I regret every time I allowed failure to dictate my course of action. Conversely, when I think of my accomplishments, the ones that matter most, the ones that give me satisfaction, are the things I persevered in doing, despite how hard it was; how stacked the odds seemed against me.

In that sense, failure isn’t just an unavoidable part of life. It is the very thing that makes life worth living.

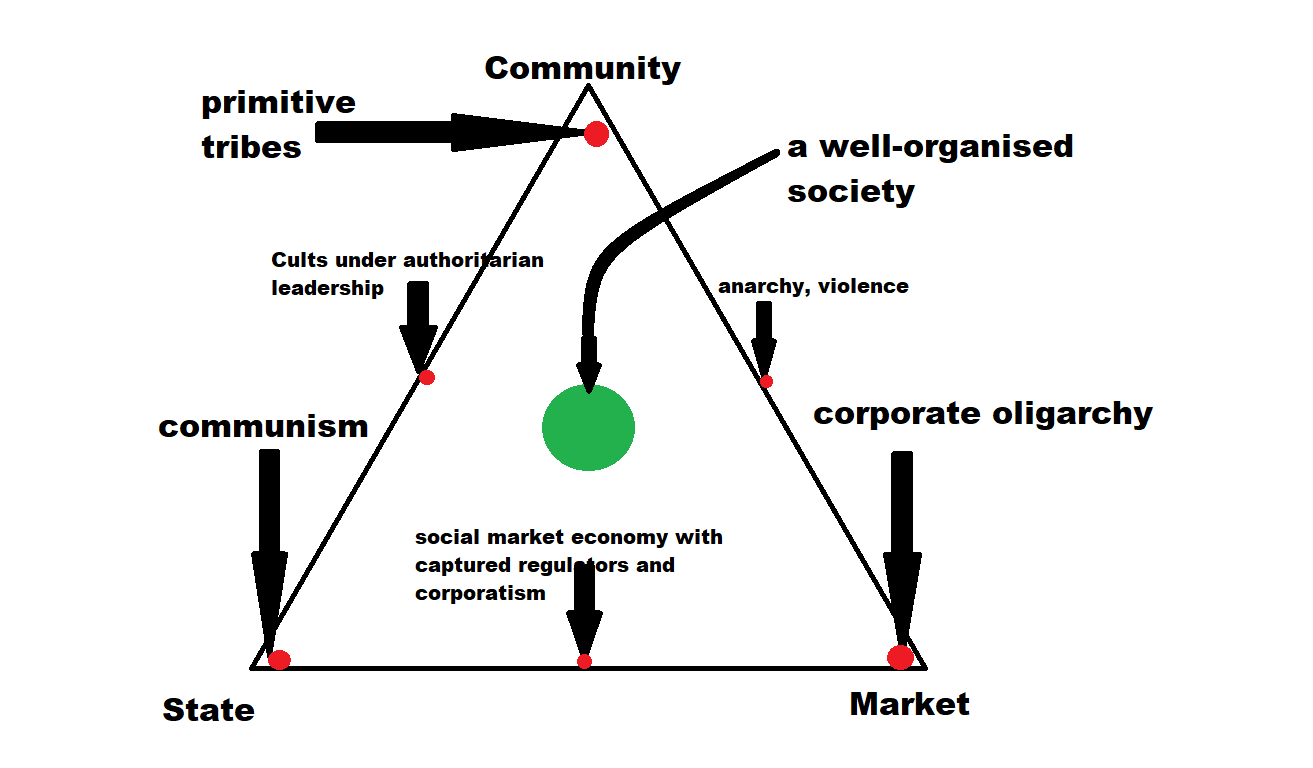

A General Theory of Society

I’ve had in my head for some time a general theory of society, that I’ve been meaning to put down in writing. Here goes:

Society – any society – consists of three essential elements: a State, a Market and a Community. Let’s take each in turn.

The State is, in its essence, the monopoly on physical force. The weaker the State is in a given society, the more physical force is dispersed between different actors. The stronger the State, the more physical force is concentrated in the State itself. A hallmark of a strong State is, therefore, laws which prohibit any form of violence, up to and even including self-defense.

It follows from this definition of the State that everything it does in some way relates to its monopoly on violence. For example, the State spends money on infrastructure. But in order to do so, that money must come from taxes. These in turn are collected from taxpayers who, if they refuse to pay, will have the money taken from them. If they resist, the State will not hesitate to use physical force to compel them out of their possessions and into prison.

Next comes the Market. The Market is the free exchange of value between actors. It reposes on the assumption that exchange is mutually beneficial. In its purest form, the Market knows neither altruism nor compulsion. Each actor enters the Market to further his own self-interest, and finds that agreement with other actors is the best way of doing this.

The final pillar of society is Community. Community is all voluntary interactions of social actors that are neither transactional nor subject to compulsion under threat of physical force, So anything that is non-State or non-Market is by definition Community. Examples of Community are families, friendships, bowling clubs, religions and board game meetups.

A key feature of Community is that it has the power of banishment or exclusion, but no other power. Another key feature is that interactions within a Community tend to be highly altruistic. Community members ‘care’ about one another, and in fact are often willing to suspend their own self-interest in pursuit of Community-defined goals and in adherence to Community-defined values.

Now comes my core hypothesis about the ideal organisation of a society:

A society can be said to be well-organised when the Community, the Market and the State all have equal weight. This is because each of these three mechanisms represents an important check on the other two. The State provides order and peace, the Community provides values and morals, and the Market provides economic rationality and innovation.

A society that has a strong State, but a weak Market and a weak Community, will tend towards Communism. The lack of (Community) moral compass will allow the State’s leadership to abuse its monopoly on power, while the lack of (Market) pressure will lead to bad economic-decision making and undermining of democracy, because consumers and businesses exert a democratising influence.

A society with a strong Market, but a weak State and a weak Community, will tend towards Corporatism, a consolidation of economic power in the hands of wealthy oligarchy, who will lack morals (e.g. fly to space with Captain Kirk in a giant dick, while their workers have to pee in bottles). Likewise, enforcement of contracts will be impossible, because that requires either the compulsion of the State or the moral impetus of the Community. Ultimately, even basic transactions will be burdened with additional costs of self-enforcement, and entire markets will collapse under that cost.

It’s rather hard to find examples of a society characterised by strong Community, but weak State and a weak Market. However, tribal societies exactly fitted this description. And while they may be marked by a degree of stability, I would argue that this comes at a high price: investment is next to impossible, nothing is there to drive human progress and innovation.

In modern political discourse it is conventional to consider society along a ‘left-right’ axis, in which two of the three essential societal elements are considered as opposing poles of a spectrum. My hypothesis suggests that in fact there is no place along this spectrum that can deliver a healthy, well-functioning society, because the third element – Community – is not represented.

That is why it is best to illustrate politics not with a left-right spectrum, but with a Social Triangle

And in fact, much of the imbalance in modern society is related to a steady erosion of the influence of Community on our daily lives. Church attendance has plummeted, people have fewer meaningful friendships and participate in fewer activities. Families are smaller and more fragmented than ever before. Indeed, we have drifted down the Social Triangle, and are approacing the bottom axis that runs between State and Market.

That is why when the Left and the Right complain about the other side, they are both right and both wrong. A good example is around Hate Speech. New laws are being rushed upon us by well-meaning, but wrong-headed Leftists to outlaw saying ‘mean things’. These laws are incredibly stupid – at best they won’t work, and at worst they will. But the question is, why is this happening? Simply put, the power of the Community to check the behaviour of society’s members is increasingly absent. We now find ourselves trying to criminalise the sort of behaviour that used to cost you friendships, club memberships and a place at your cousin’s dinner table.

Markets are also malfunctioning in ways that Right-wingers find hard to explain away. It turns out that excessive greed and amorality are themselves a form of market failure, because any asymmetry between market participants creates an opportunity for sharp practice – information is imperfect, bargaining power is lopsided. Absent Community, the only way to check those immoral excesses is ever-more costly regulation. That in turn creates opportunities for regulatory capture and barriers to entry for new market participants. We find ourselves in a social market economy that is neither very social nor very market.

What is the solution? Clearly, it is to restore some sense of Community – common values, a common purpose, a clear set of religious dogma and a shared moral code. Adam Smith understood the importance of this intuitively, (even if Karl Marx was less perspicacious in this regard).

Now, this is all well and good, but do I have any more practical suggestions or is this just another ‘everything is awful’ blogpost? Here’s my three step plan:

- Awareness. Stop pretending like our Community doesn’t matter. Restart a conversation about what our values are, what we can agree on, and how we can come together to pray and play – knowing that is every bit as important as who our State leaders are or how our economy is working.

- Subsidiarity. An interesting result that comes out of the social triangle is the question of scale. It turns out the Market works ever better at scale, and the State too seems pretty able to work at scale. But Communities don’t seem to work very well at scale at all. Insofar as altruism is a key ingredient, it’s really not possible to have empathy with a million other people, much less 8 billion. In other words, today’s society is too big for real Community to exist. Not only is globalism a terrible idea, in fact, we need to break nations down into pieces that are well proportioned for Community to prosper. This suggests devolving more of the Market and the State to smaller scales – local government and buy local goods.

- Stop uncontrolled immigration. Yes, there I said it. Immigration is very bad for Community, for the obvious reason that immigrants are least likely to share the common values that bind people together in voluntary ways. Immigration erodes Community and splinters society.

- God. That’s right. The big guy. Flowing white beard. Turns out, not only is He almighty, but He’s also quite good for creating the conditions under which Communities can flourish. He sort of works as a rallying point and an anchor for common values and beliefs.

- Get the hell offline. I don’t believe the internet is the cause of failing Community. After all, the excellent book Bowling Alone came out when the internet was still in diapers. But I also don’t think the internet can be part of the solution. If you want real Community, you should get off this damn computer, go outside and meet people. Join a choir. Or a rugby team. Or take a pottery class.

On the fall of Avdiivka (and Western political rationalism)

Can’t leave the news for even a weekend?

I spent a rather pleasant weekend with my family in Transylvania, among other things visiting the spectacular Salina Turda salt mine. I was less than 200 kilometers from the border with Ukraine, but well over a thousand from the beleaguered city of Avdiivka – and my mind was further still from the horrors its name evokes.

So it wasn’t until this Monday morning that I learned the city’s defenses had collapsed in a disorderly retreat; one which left the thousands of Ukrainian soldiers to run along the only remaining road out; or to be killed; or to be captured by the storming Russians. The collapse of Avdiivka also punctured a gaping hole in Ukraine’s longstanding defensive line inside the Donetsk Oblast, through which Russian forces are storming as I type these words.

Asymmetric warfare: shovels against balcony flags

The Russian troops have at their backs an overwhelming superiority in shovels (i.e. airplanes, artillery, drones, missiles), in troop numbers (essential for troop rotation), in morale and in momentum. Their political leader enjoys unprecedented popularity, a mostly buoyant economy and newly forged alliances with the most powerful economy in the world, China, whose leader has just refused to even speak to the Ukrainian president Volodomyr Zellensky.

What does Ukraine have at its back? Despite the promises of support for ‘as long as it takes’, the US Congress has decisively denied a funding package of 60 billion dollars to rearm its proxy ally. America’s most popular journalist (by viewer numbers) just conducted a soft-ball interview of President Putin that was watched by over 100 million Americans; and the clear frontrunner for the presidency in November has vowed a policy of negotiation and disengagement.

Meanwhile the EU is out of military cadeaux (shells, F-16s, Leopard IIs) to send east, and is facing a run of elections likely to further erode the political appetite for any form of solidarity more painful than photo-ops and impassioned speeches. Its latest economic forecast, meanwhile, shows anemic growth and deteriorating public finances, while Polish farmers are blocking their Eastern border to stem the flow of cheap wheat, Ukraine’s only real remaining export.

A badly scripted TV president with a predictable ending

The worst part is, this was all so depressingly predictable. I’m no great military tactician, but it didn’t take me long to understand that this war was entirely unwinnable for Ukraine, at the very latest once the Russians had declared the territories in dispute to be an integral part of the Russian Federation itself. Absent direct military intervention from NATO leading to a catastrophic escalation, Ukraine’s battlefield valor could do no more than prolong the inevitable, and claim the lives of ever more young men. You only need to have played a few games of Risk to understand that when the troops stack sufficiently high on one side of a battle, the outcome is not seriously in question.

Likewise, one didn’t have to be a great statesman to see the dangers of driving Russia into China’s arms. Nor was a Nobel Prize in economics needed to understand that the rise of BRICS meant there was limited scope for Western sanctions to dissuade Putin from his course of action, or that the politicisation of the Bretton Woods financial system would backfire, undermining its credibility and hastening de-dollarisation.

Why, then, did the West persist? And persist it surely did – with months of declarations of unwavering support, with ever more risible packages of sanctions, with arsenals of last-generation military gear. Why did not a greater statesperson emerge, look three moves ahead and realise where this was all heading? Why did he not take Putin quietly by the elbow, smoke a cigar with him and hand over just enough territory to restore the peace and allow everyone to declare some sort of victory?

Did Big Gun bring out the big guns…?

The internet is full of conspiracies these days. When Klaus Schwab, Bill Gates and George Soros are not busy planning mass depopulation of the planet, it’s Taylor Swift and her devil cult rigging the Super Bowl so her (presumably Satanic) boyfriend’s team can win (they play in red! Coincidence? I think NOT).

According to the sages of this school, the powers that be knew full well Ukraine was a lost cause from day one. They nevertheless wanted to draw Putin into a messy conflict, stir up a heightened sense of threat and play on that in order to be able to fill the arsenals of Washington and Brussels with next-gen NATO weapons, all on the dime of the West’s generous taxpayers. They foresaw the fall of Avdiivka long before I or even Putin, but they frankly didn’t care, and will watch indifferently as every rick and croft east of the Dnieper gets burned. The shadowy cabal pulling the strings here is the military-industrial complex, and it’s all about the money.

…or is the truth even more depressing?

I don’t buy it. Don’t get me wrong: I’m not saying Honeywell, Raytheon, Lockheed Martin et al do not actively lobby to promote hawkish policies – this they have always done. Nikki Haley is just Dick Cheney in heels, and Dick Cheney was just Henry Kissinger with better glasses. But their influence is limited, their reach finite. They can tilt outcomes at the margins perhaps. They cannot, however, cause a Ukrainian flag to hang from every balcony from San Francisco to Helsinki. They cannot cause the West to lose its collective mind and throw all its political capital, hundreds of billions of dollars and its very economic hegemony into what is obviously a lost cause.

My theory is what we have witnessed with the fall of Avdiivka is the collapse of something much more central to Western civilisation. It is the loss of political rationalism in Western decision-making. The West no longer has the ability to apply reason to its political calculations. The carefully groomed tradition of considering consequences and working backwards from there to determine the best future course of action is out of fashion. Instead, decisions are made on impulse – mad gambles steered by the public mood, by passions and by the moment.

Baby needs a new pair of shoes!

Of course, when the gamble goes bad, there is an emotional reaction. A sort of heart leaping into the mouth, as the gambler sees that he somehow did not make the flush on the river card, even though he ‘had had that feeling’. That is what we see in the news today: multiple reports of ‘shock‘ at the news from Ukraine, a sense of ‘gloom‘.

This is precisely the moment when you should cash in your remaining chips, take stock of the experience and review the path that led you to such bad decision-making. Sadly, for most gamblers, this is not what actually happens. They make excuses, double down, and continue with the bad decisions. The reason Avdiivka fell is because Congress did not hastily enough approve the additional funding. We must send more to Ukraine, we must press Putin harder. Perhaps another round of sanctions (this time targeting the lucrative Russian canine toothpaste market)?

In my heart, I want to believe we can regain our ability to apply political rationalism. But if I were a betting man, I’d cash in my chips and go buy a 500 litre rainwater filter.

Ma 18ieme lettre

Cher Daniel,

Joyeux Noël, mon fils. Je me retrouve en Angleterre avec Joanna ma femme et ta sœur Daphné. Ta sœur Anna est en Mexique avec son petit-ami.

Encore des fêtes que je sais pas partager avec toi!

En tout cas, je te souhaite de beaux cadeaux (je t’ai envoyé un petit quelquechose) et de la joie.

Bonne annee

In defence of free speech (again)

Mal- mis- dis-, a neo-Marxist twist?

This is not the first time I’ve written about the importance of free speech on this blog. Since my last post on the subject, however, Western society’s commitment to the ideals that underpin free speech has waned further. We have endured not only sinister revisionist attacks on ‘problematic’ heritage statues; not only the mainstreaming of the censorious concept of ‘hate speech’ and ‘hate crimes’; but also an entire, carefully orchestrated, campaign to eradicate free speech on the internet, including the mainstreaming of some outright ludicrous euphemisms like ‘malinformation’. At least, it would be ludicrous if the stakes weren’t so very high – the wholesale collusion of government in managing the flow of public information is beyond dangerous, as evidenced both by Laura Dodsworth’s excellent book and the Twitter Files.

The diarrhea icing on this shit cake is the rise of the most revolting class of idiots in the Censorship-Industrial complex, the odious legions of ‘fact checkers’. Really, these are just self-appointed, highly-opinionated urbanites of the burgeoning Laptop Class – rebranded journalists with hutzpah – but it’s remarkable how easily everyone fell for their sham-show, and how effective they have been in fostering acceptance for the abolition of free speech online.

I find myself wondering whether the very act of advocating for free speech might soon be targeted by the censors – is it not, after all, the crime of ‘incitement to mal-, mis-, disinformation’?

I don’t agree with your cliched Voltaire quote, but I’ll defend to the death your right to use it as a section header.

It’s always good to hash over the core arguments for allowing even the most outrageous opinions to be voiced as ‘free speech’. First of all, if the goal of inhibiting free speech is to safeguard against falsehood, then censorship does an appalling job. This is because it presupposes not only that censors have pure motives, but also that they know what the truth is to begin with. As the Covid debacle showed clearly, this is not the case. In fact, it is precisely through the freest and most open exchange upon the marketplace of ideas that we begin to approach truth – an asymptote at which we never arrive.

Second, on a purely practical level, even when it’s well targeted at actual falsehood, censorship is mostly self-defeating. The ‘Streisand Effect’ takes hold, and people’s natural instincts draw them to the very pink elephant you are trying to get them to not think about.

Third, censorship is like pregnancy. You can’t really have a little bit of it. Because even when a case can be made, theoretically, for blocking speech at the extremes – for example shouting ‘fire’ in a crowded theatre – it tends to slip, over time, towards more and more authoritarian restrictions on speech. Interestingly, even this censorship straw man doesn’t hold up very well. Try actually shouting fire in a theatre and see how many people stampede. Probably none. It may be that once upon a time, with lower fire standards, such a thing might have happened. But then the solution wasn’t censorship, it was better fire-resistant building materials and sprinklers.

The case for ‘free hearing’

And yet, the recent debate has caused me to realise that none of these classic arguments against censorship is the most compelling defence of free speech. What matters more than all of the above is the effect censorship has on the audience.

To understand why, consider what effect free and open debate has on those who listen to it and participate in it. Much of what is said will be false, or only partially true. When anyone is free to claim anything, it becomes more important to use one’s own sense of discernment in analysing those claims. At its worst, of course, censorship stifles inconvenient truth. But even when it is at its best, it diminishes the audience’s capacity to exercise the mental muscles of discretion. Like people who use Google Maps to get around, the minds of the audience under (even benevolent) censorship regimes become lazy and less able to navigate their way towards the shimmering city of Veritopolis.

This is an important point to consider. Because the right to ‘free speech’ is often defended as an individual right. Yet the right to ‘free hearing’ is a social right. It is the right we all enjoy to be tricked and fooled, the right to believe something stupid, to learn from that experience and to become more discerning. Especially for the malleable minds of young people, this is a right that must be exercised widely; all the way ‘from the river to the sea’.

My review of Williams’ “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof”

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof by Tennessee Williams

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

We all remember the pain of reading Shakespearean plays in school. Sadistic English teachers with shattered dreams of being something better forcing us to learn whole passages by rote …the quality of mercy is not strained…, without once reflecting on the irony of their own lack of mercy.

If you had intellectually snobby parents like mine, the closest to sympathy their innate veneration of the Bard would allow, would be the grudging admission that, “well, really Shakespeare is not meant to be read. It’s meant to be performed.”

Actually, during the later years in which my own intellectual snobbery got me reading his plays autonomously, I never found this to be true. Unless you’d already studied Henry CXXII part VI, live performances went too fast; you missed too much of the subtle word play or the historical context. Idem for Ibsen. As for my favourite playwright Miller, I always found the dialogue to be so supremely evocative of the scene that if anything a live performance introduced risks of spoiling the perfect acting I imagined in my own head.

However, for Tennessee Williams, I don’t think this is the case – at least not as far as ‘Cat on a Hot Tin Roof‘ is concerned. I read the play, never having seen it staged nor having watched the film. My first impression was the dialogue came across as hammy, overdone and at times (needlessly and repetitively) redundant, (such that the point could have been made with fewer lines and more subtext). To wit, the titular feline metaphor is hammered into the reader’s ears in Act I. Not once, but twice.

Moreover, if you are looking for an entertaining plot or clever character arcs, you have come to the wrong place. Williams is writing as an American realist – he sees little scope for moral progression, at least not in a story that takes place over one steamy night in the big house of a Southern plantation. This left me wondering what the big deal with Cat might be, whether it wasn’t just a mediocre script that benefited unduly from good timing and a nascent American Empire, hungry to grow cultural roots in the fertile soil of its burgeoning economy.

On reflection, though, it occurs to me that these shortcomings would be somewhat attenuated in a live performance. There, we can imagine how strong performances might make the Southern nouveaux riches sparkle: the droll alcoholism in the fallen favourite son Brick, the desperate aching of womanhood in his wife Margaret. The bellicose, base honesty in his father, Big Daddy.

Indeed, Cat might be as much about the atmosphere as the story. It evokes a particular mood and feeling; which perforce comes alive not in the words themselves, but in how they are spoken and in the silences that can unshroud a deeper meaning. This is not a finished piece of literature. Rather, it is a set of instructions to the actors and director, and should perhaps be read by them and them alone.

View all my reviews

Non-fiction is just fiction written by authors who are too lazy to think up a good story

Shady Characters: The Secret Life of Punctuation, Symbols & Other Typographical Marks by Keith Houston

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

Sure, non-fiction is a way of getting a lot of ‘facts’ down on a page – some of those facts might even be interesting. But you can do that in fiction too; oftentimes much better. Think of how much historical context is written into Trollope’s Vanity Fair; how much social history of the early 19th Century, all effortlessly woven in to a cracking good yarn. Without the constraints of a good story, non-fiction authors often give in to the temptation to dump an enormous amount of information in an unstructured, unsorted way that leaves the reader overwhelmed, confused or just plain bored. This is why I don’t read a lot of non-fiction.

For Keith Houston’s Shady Characters, I made an exception. This was partially because the subject matter – the origin stories of punctuation symbols, weird and common – was sufficiently quirky and yes, so incredibly nerdy, that it seemed bound to read a little differently, even for non-fiction. It was also because the book fell into my hands at a moment when I had nothing else to read.

In all, the book was not a complete disappointment. I learned some wonderfully useless things about punctuation marks I never knew existed, like the interrobang – a short-lived 20th Century hybrid of the question mark and the exclamation point, which looks like this: ‽

More usefully, the twisted road to modern typography takes you past some genuinely interesting historical waypoints. I was particularly fascinated by the detailed description of the typesetting used by Johannes Gutenberg for his 42 line bible, which was, after all, the ‘Star Wars: A New Hope’ of books. It blows my mind to think that with all the algorithmic typesetting we have today, the line spacing used to justify the first ever printed book is so perfect that it remains, to this day, the best typeset book in the history of print.

Another plus point (see what I did there?) was Houston’s clever use of the punctuation, fonts and even writing styles he describes, in that respective chapter to illustrate the examples he’s discussing.

All that said, Shady Characters succumbs to the original sin of non-fiction books, allowing its author to indulge in detours and asides that made certain paragraphs seem like we would never get to the next ¶ (which is called a ‘pilcrow’, in case you never knew).

Even more irksome is the New York Times-reading, smug intellectualism of the author. Just as the nouveau-riche indulge in conspicuous displays of wealth in a way ‘old money’ never would, American intellectuals like Houston always try too hard to be literate and clever, made desperate by their transatlantic cultural inferiority complex. In doing so, they sacrifice something of the message in pursuit of their ostentatious displays of learning. Bad writing is when, while reading, you can hear the sound of the author typing. In reading this book, there were moments when the sound of Houston’s ego echoed with every keystroke.

With fiction, it is the story that acts to curb the author’s ego, because he or she is bound by the plot and by the fictional characters, who – once defined – begin to tell their own stories. In this book, Houston had no characters to whom he had to stay true (at least not in the figurative sense).

I ask you, is it so hard to weave knowledge into a true yarn‽

View all my reviews

My review of Graham Greene’s ‘The Power and the Glory’

The Power and the Glory by Graham Greene

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

It is often said of writers that they must first read, and that if you want any hope of being a great writer, you must be a great reader. I don’t know if that’s true – I have known very gifted writers who read very little, and voracious readers who could not string a sentence together. One thing, though, I can say: certain books are so brilliant that they inspire me to want to be a better writer. There is no particular genre, or subject or period in history that these books belong to. What they all have in common is that they touch upon some ‘essential truth’, something that the writer himself knows to be true, and the force of his conviction leads me to be intrigued by his truth, to accept it into my own canon.

Graham Greene’s ‘The Power and the Glory’ reeks of exactly this kind of essential truth. A devout Catholic, Greene naturally questioned the shortcomings of his own Church. Like all thinking members of the Church of Rome, he must have been deeply frustrated with its contradictions, pettiness and displays of pomp and pride. In ‘The Power and the Glory’ he lays bare this frustration, by showing the Catholic Church at its most essential.

No, this essence has nothing to do with the Pope in Rome, or any great bishops, or the inner machinations of Opus Dei. Rather, it is a disgraced Mexican cleric of low rank – the ‘Whiskey Priest’ – on the run from the communists who control that state. These communists have a fiercely atheistic zealotry; one that is deliberately reminiscent of the Spanish Inquisition.

The priest’s persecution is set up to be deliberately Christ-like, in that he must endure hardship, insults and deprivation. And yet, just as deliberately, we are given ample reminders of the fact that the Whiskey Priest is no Christ figure. He is a grievous sinner, guilty of all seven of the deadly variety. His life before the Communist revolution was one of pride; of lust leading to the fathering and abandonment of a bastard child; the sins of gluttony and sloth; and all of this seasoned with an unhealthy dose of envy of those of his peers who had risen higher in the Church than he.

Now a fugitive, every policeman in the state hunts him. Yet he manages to elude justice for weeks. The pious peasants respect his office even if he no longer does, and they pay a huge price to hide him from the Communists. His fugitive status is not even a form of martyrdom, because he fails to uphold even the most basic offices of the Church with any remaining shred of dignity, despite the people’s need for his spiritual guidance. Rather, he flees because he is a coward.

The story is made gripping by the detailed, gritty descriptions of the scenery (beetles exploding against the walls, swamping hot rivers with lazy, rusted boats anchored) and the people (the odd-ball ex-pats, the corrupt police lieutenant, the indolent villagers). But its true appeal lies deeper. We want to know the Whiskey-Priest’s faith precisely because his whole persecution amounts to a deeply religious confession – a path to God and the religion he had never truly known, all through the glory days of his priestly reign. His path to God only opened up the day he was tested.

Yet Greene is too good an author to allow his Whiskey-Priest moral redemption on earth. In the brief moment in which he achieves safety and a degree of comfort, we see our anti-hero quickly revert to his old, sinful habits. The message from Greene is clear: there is no path out of sin except the unconditional acceptance of God and belief in His divine mercy.

As a religious person, I relate to this story on many levels. But though its essential truth resonates with me, I cannot say how it would strike someone with different philosophical leanings.

Would the power of Greene’s faith, exposed through this wonderfully crafted tale, ring as true in the ears of a 21st Century atheist, an adherent of the cult of The Science? I somehow believe it would.

But then again, I’m the sort who believes lots of things – like the only son of God dying on a cross outside Jerusalem, two thousand years ago.

View all my reviews