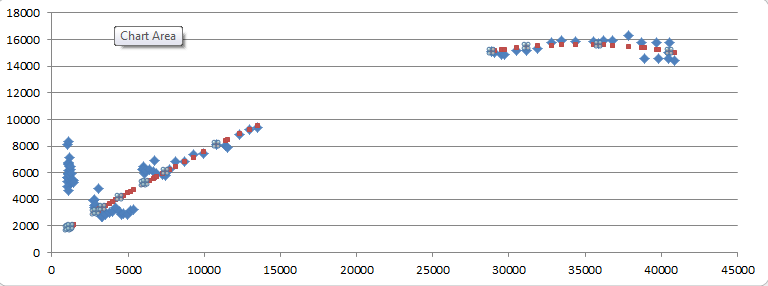

What is the one thing you associate most with Westerns? Horses, right? Wrong! There are actually almost no horses in any Western movies you will ever watch. To prove the point, consider this picture of Clint Eastwood from the classic Rawhide, standing next to a ‘horse’:

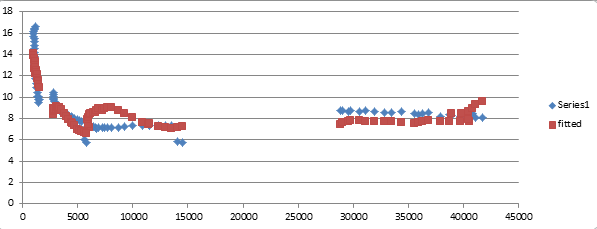

From this photo, we can see fairly clearly that the ‘withers’ of the equine in question (i.e. the ridge between the shoulder blades) reach up to just below Eastwood’s nipples. As any artist who has studied human anatomy can tell you, the distance from nipple to the top of the head is about 25% of total height.

Now we know Eastwood to be a tall man – the internet reliably informs me that he is in fact 193cm (6’4″) in height. Therefore we can estimate the distance from Eastwood’s crown to his nipple to be 48.25cm. Given the ‘horse’ and Eastwood are standing side by side, this yields a height from withers to hoof of 144.74cm.

But here’s the rub, fellow movie-watchers: Any equine below 147cm (14.2 hands) is not a horse, rather a ‘pony’! In fact, the animal pictured here is only a tad bigger than Coca, the pony my 8 year old daughter rides at our local stables.

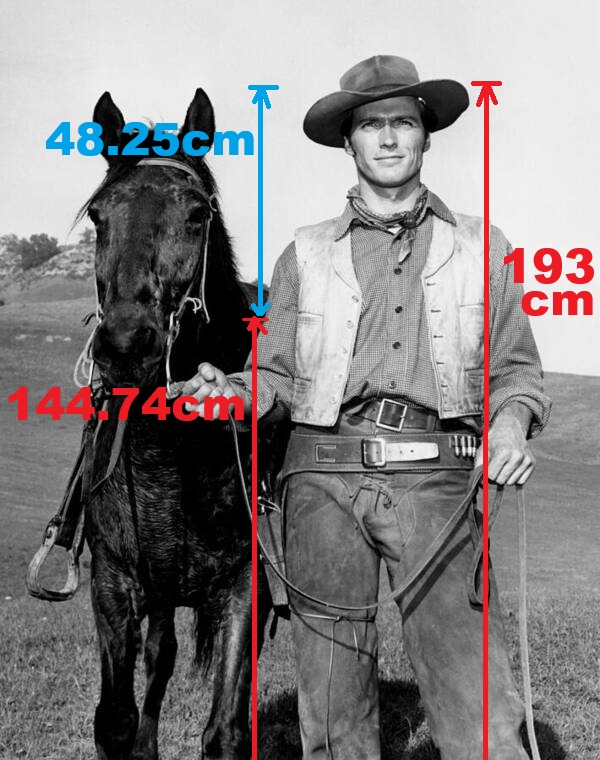

Of course, my eyeball estimate could be a centimetre off, but even being generous, this animal barely crosses the threshold. To drive the point home, compare Clint with historical photos. Here we have one of the most famous horses in American history, Comanche, with his 185cm (6’1″) rider, Captain Myles Keogh. Note how Keogh’s eyes (eyes to crown: 0.5% of body) align with Comanche’s withers. Using our body proportions method, we can estimate the sole equine survivor of Little Bighorn stood 173cm (17 hands) tall – a good size horse, by any standards!

Now consider this: if even mighty Clint had such a diminutive mount, what of the other, mostly shorter, cowboys who grace the silver screen? Go back and watch the movies and you can answer the question for yourself.

In reality, if actual cowboys tried to ride off into the sunset on such little ponies, saddlebags, guns and all, the animals would not get them more than a few miles from Tombstone before collapsing with fatigue. So why do directors choose to pair these mighty tough guys with the sort of puny ride that daddy’s little princess canters around with at overpriced stables in the Connecticut suburbs?

A few reasons: First, because the pairing automatically makes the director’s cowboy look bigger than he really is – that’s almost always a good thing. More practically, unless you are supremely athletic and dressed appropriately, jumping up onto a real horse is quite hard to do. And having your grizzly desperado drag over the mounting block so he can scramble his way into the saddle would take away from the magic of the screen. Ponies are also smaller, thus cheaper to feed and stable. And if the actor loses his stirrups mid-scene, he is less likely to be hurt from the shorter fall.

Most importantly, Hollywood does this because they can get away with it. Few movie-goers spend much time with actual horses, so they have no point of reference in real life for how big a horse should be.

It’s yet another reason to get off the couch, away from the phone, climb into the saddle and ride into the saloon of real life.