A knave by any other name…

One of the worst things you can be called nowadays is a ‘conspiracy theorist’. It is right up there with ‘anti-vaxxer’, ‘COVID denier’ and ‘Trumper’ as a dysphemism with the weight of mainstream, neo-liberal social condemnation behind it. Very few of those who wield it as a ball-and-chain in the melee of internet comment battles ever stop to consider what the two words in the compound actually mean.

To ‘conspire’ is for two or more parties to agree in secret a course of negative action. ‘Theory’ is a much abused word in common parlance. As Brett Weinstein has been at pains to point out over at the Darkhorse Podcast, in the scientific sense a ‘theory’ is a well-substantiated explanation of a phenomenon, which fits together laws, hypothesis and observational data.

A Wuhan conspiracy? Or just people breathing at the same time?

So when those advancing the Lab Leak Hypothesis concerning the origins of COVID were branded conspiracy theorists, the branders were unwittingly using doublespeak. Because in fact no collective secret agreement was needed to conceal the mistake that is hypothesised to have occured at the Wuhan Institute of Virology in late 2019 – a simple denial on the part of those involved will suffice, combined with an unwillingness to allow any meaningful investigation. Nor does the hypothesis in any way hinge on leading virologists like Peter Daszak from EcoHealth Alliance sitting in a smoky back room with President Xi and Tony Fauci. He might simply pursue naked self-interest in aligning himself with the statements of the Chinese Communist Party. And likewise, the media who skillfully ignored the leads that were publicly available last year needn’t have been party to any conspiracy; their distaste for Donald Trump was enough for them to shy away. Since no one has a positive motive to admit the truth, there is little need to assume they would agree to withhold or suppress it.

Nor is the hypothesis necessarily worthy of earning the title ‘theory’, as it lacks the weight of rigorous testing to which hypotheses should be subjected.

Are so! Am not! Are so! AM NOT! ARE SO!…

But none of that matters, because the term ‘conspiracy theory’ has assumed a meaning distinct from the sum of its parts. It now merely infers, ‘a statement or line of reasoning that is out of step with orthodox views, and which is therefore worthy of public derision, and association with which should cause a loss of credibility for its proponents, advocates or even elucidators.

Like its siblings in the medical and political spheres, the conspiracy theory label does much damage to our ability to understand and find positive solutions to important problems. Those unjustly branded with this label are shoved further away from the centre, making consensus more difficult. And the fact-free, lebel-heavy nature of such accusations is at best lazy, at worst feeds a cycle of ad hominom attacks and ego battles. Reason emerges as the big loser.

Content warning: this section has been fact-checked by Facebook’s independent shareholders and found to pose risks to Facebook’s share value

All this is a preamble to address an example of just such a ‘conspiracy theory’; one which has received surprisingly little air time, even among those whose natural scepticism earns them the collective designation ‘tin foil hat brigade’.

I am referring to the role Big Tech has played in steering the political discourse. Anyone paying attention cannot be ignorant of the considerable power these tech monopolies now have over virtually every aspect of our lives. Many on the neo-liberal centre left didn’t blink when, in the wake of controversial election results in January, Jack Dorsey used his editorial control of Twitter to silence the democratically elected leader of the Free World. They barely raised an eyebrow when, shortly thereafter, Jeff Bezos used his control of servers to shut down Parler, effectively silencing half the political voices in the US. Because, well, Orange Man Bad.

Yet they ought to have been concerned. You don’t need to be an exceptional scholar of the history of tyranny to appreciate that when that kind of power exists, it will not exclusively be used against your political foes. And so there was somewhat more of a collective gasp when, a little later, Facebook acted to effectively shut down the virtual lives of millions of Australians, when that country dared try and enforce the intellectual property of its free press.

But few have wondered about the role Big Tech is so evidently playing in this ongoing pandemic response. No one seems to ask how it is that, barely 16 months ago, no country in the world would have considered lockdowns as any legitimate pandemic response, yet the media and social media were virtually unanimous in supporting these measures. No one wonders why Alex Berenson’s pamphlets which make this very point and others were banned from Amazon, saved only by a personal intervention on the part of Elon Musk. No one queries how numerous YouTubers, from Iver Cummins to Freddie Sayers to TalkRadio have faced content removel, shadow banning and demonitisation, all for the crime of daring to engage in public debate on the most important and unprecedented policy change of the Century, and at a time when it was literally illegal for us to have such discussions in person.

Q: Qui bono? A: Page, Gates, Zuckerschmuck, Dorsey, Bezos…especially Bezos

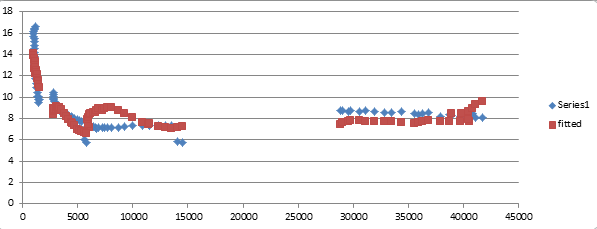

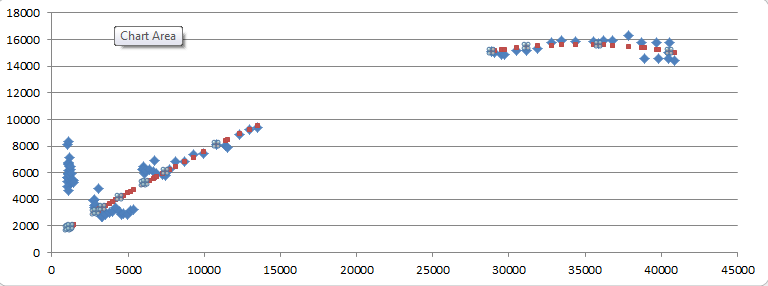

This lack of questioning is all the more surprising when you consider the obvious motives these companies have in promoting as much panic and overreaction to COVID as possible. By closing coffee shops, people take to Twitter and Facebook to stay in touch, with Google running everywhere in the background. For this they need computers, sold to them by Gates. And by shuttering physical stores, more people shop on Amazon, and Bezos pulls ahead of Musk in the race to be the world’s billioniest billionaire.

But don’t take my word for it. Just look at what happened to the share value of all these publicly traded companies in the wake of the pandemic. Without exception, they profited massively. And likewise, as things have threatened to return to normal, share values begin settling down again. Then suddenly: second wave, third wave, UK variant, South African variant, Indian variant, limited natural immunity, vaccinate yet wear masks forever…

Of course, this is a crazy ‘conspiracy theory’. But my point is that no conspiracy is actually needed. In fact, given these publicly traded companies have no legal duty to tell ‘truth’, yet do have a fiduciary duty to maximise shareholder value, you could easily argue it would be illegal for them to not downplay content that tends to reduce lockdowns and encourage people back into the physical world. Evil? Perhaps. But that’s business. And with business decisions increasingly being taken by AI, it’s not even clear that an unscrupulous human being is required to achieve that outcome. Skynet could be doing it all on its own.

When all is said and done, very little is being said and nothing is being done

What is most worrying is the relative lack of meaningful post mortem. On any of it. By which I mean: On face masks. On lockdowns. On border closures. On the media’s role. On Big Tech’s role, and how policy decisions are arrived at. On the role of Big Pharma. On the origins of the virus. On the role of the WHO. On the role of Anthony Fauci and other ‘medical and scientific experts’, and how consensus is reached within their hierarchies. On the side effects of mRNA vaccines. On why large-scale clinical trials were not ordered in April 2020, (or October 2020, January 2021…or even today) on ivermectin, given its safety and the clear evidence it might be an effective, if not ‘pandemic ending’ treatment.

At this stage, these questions are becoming increasinly academic in nature. But it is nevertheless important that we answer them, and make a concerted effort to address the weaknesses that have allowed a relatively mild pandemic to do so much damage to our societies, our economies and our well-being.

But there is still time to ask the right questions

As a start, I would suggest we need to consider the harms of informational monopolies in terms that go beyond classical market failure (consumer prices) and take into account societal harm and harm to our democracies. We need to take a hard look at how our institutions – academia and the medical establishment – perform in light of funding, hierarchy and the process of peer review. We need to look at how media voices create and sustain particular narratives, including the role of corporate control and ownership in mainstream media channels.

Oh, and we need to consider how the Chinese Communist Party is using its high degree of centralised power to achieve favourable political and market outcomes outside its own borders.