View from the roof of the Reichstag in Berlin

Dear Daniel,

I am writing to you in English in the hope that you will have learned some English at school by now and can read this.

The summer is over! I hope you had a nice break and got plenty of sunshine (but not too much heat!) in Southern Europe. We avoided going south this year because the heat is just too much. Instead, I took your sister horseriding in Ireland and we visited England and also Normandy. We also went camping in the Ardennes (which is full of Dutch people).

Anyway, now it’s back to school. I hope you have a great start to the year – good teachers or at least tolerable teachers – and that you are enjoying seeing your friends again.

As always, I think of you a lot – especially when I am doing things like cutting wood or building the woodshed at home. It makes me a little sad that I can’t do these things with you, as a father really should.

Maybe one day.

Meanwhile, all the best from me.

Love,

Dad

Once upon a time, there was a fair, prosperous land known as the Twin Kingdoms. It was so named because it was divided neatly in two halves by a swift river. These two halves were left by the dying king to his twin sons – the right half to Prince Cleo and the left half to Prince Tharm. The King thought both to be strong, honest rulers, who loved each other and their subjects. Their father had fought many wars to bring them peace and prosperity, and both princes swore to him they would work to protect it.

When it came time to marry, Prince Cleo searched wide and long, threw many balls, until finally he made his choice: Hannelore – she was neither the wealthiest, nor the wisest, nor the fairest of the maidens in his realm, but rather was a good mix of all these things together. She loved her fiancé and he loved her.

When the banns were announced, his brother Tharm – full of love – embraced Cleo and wished him every happiness. However, as the wedding day grew nearer, Tharm began to have jealous thoughts, for he had yet to find a bride of his own. The night of the wedding, when all were dancing in celebration of Cleo and Hannelore, Tharm’s eye fell upon a lesser nobleman’s daughter – frail as a flower and as beautiful as a whole bouquet. Prince Tharm danced with her for so long that the noblewomen all took note. Her name was Mischa, and her beauty far surpassed that of Hannelore’s.

That very night, just before the newlyweds departed to their honeymoon, Prince Tharm stumbled atop a table, took a draft from his ale and declared aloud that he too had found a bride. He lifted the frail Mischa up in his strong arms and she blushed as he kissed her full on the lips. The crowd erupted in applause, and declared this the most joyful night in the history of the Twin Kingdoms. Only Cleo and Hannelore, who had grown in each other’s confidence through their long courtship, exchanged a quick glance of concern.

For many long years thereafter, all seemed well in the Twin Kingdoms. The harvests were good and the Twin Kings, as they were now known, made good on their promise to rule wisely and selflessly. Queen Hannelore bore Cleo seven children – and after each new prince or princess had come, Queen Mischa seemed to follow, as if to preserve the balance, or perhaps to compete.

Then one year, when winter fell, a violent storm swept across the Twin Kingdoms, uprooting trees and sending them hurtling down the river, destroying the bridge that linked the the Left Kingdom with the Right. Both Kings took action, riding out into the storm with their bravest men to secure the granaries, save the flocks and lead the peasants to safety. Queen Hannelore sat in her high tower, comforting the infant prince at her chest, while the other children gathered about her.

Suddenly, there was a fluttering at the tower window. A crow entered the chamber and to Hannelore’s astonishment, it transformed into a woman – tall, unnaturally pure and pale, with jet black hair and black eyes to match her long black velvet dress.

“Fear not, O Queen,” spoke the witch (for Hannelore knew it could be nothing else, and drew her children protectively around her. “I come with ill tidings, but I come also with a gift.”

“I want none of your tidings,” replied Hannelore. “Still less do I want your gifts. Leave now before I call the palace guards.”

But the witch continued as if she had not heard this. “The good harvests are over. Now disease and famine will come to the Twin Kingdoms.” She paused and cast her jet black eyes over the seven children gathered at the mother’s feet. “Many of the young will die and your own children will not be spared. Unless…” Here she drew from within her sleeve a vial, containing a shimmering colourful liquid. “…you accept to have them take this potion, which protects from all disease and will guarantee them long years of life.”

The thought of saving her children made Hannelore pause. “And what would you ask in return?”

“Nothing at all.” replied the witch. “Only that you hold me in better regard, for I wish to be a friend of the Twin Kingdoms.”

However, Queen Hannelore had grown wise. She knew that nothing was given for nothing. “Guards!” she called, and in a moment the doors flew open and the King’s men entered with halberds at the ready. The witch gave a ghastly cry, smashing the vial of potion on the floor and jumping out the window into the storm before the guards could reach her.

When the storm lifted, the Twin Kings saw that much of their Kingdoms had been laid to ruin. The winter that followed was long and hard, with snows lasting well into June. Just as the witch had foretold, hunger took hold of the Kingdoms, and disease began to spread, taking the weakest to their graves. One by one, Queen Hannelore’s seven children fell ill, and though she tended them with the greatest of care and devotion, all died, save the youngest prince, who bore his father’s name. This young Prince Cleo already resembled his father, and as the hard years went on, he grew to be a strong man in his own right; ever serving the Kingdom, ever by his father’s side.

Things were very different in Left Kingdom, however. To everyone’s astonishment, Queen Mischa survived the disease despite her frailty, and so did all seven of her princely children, and many others in her court besides. As the years went on, Cleo and Hannelore were made less and less welcome in King Tharm’s Court, though the witch was often seen there. Worse, rumours were spread among the common folk that Hannelore had denied them a great potion, and that they had suffered needlessly because of her vanity. Distrust was sown across the mighty river and the work to repair the storm-damaged bridge came to a halt.

When the springs came early again, and the summers once more grew long, King Cleo and his son crossed the river to meet Tharm and make common plans for a harvest. To his astonishment, he found his brother asleep, slouched in his throne and uninterested in making any plans.

“I have ceded my power to the Council of Seven Children. Together with their many advisors, they rule the Left Kingdom in my name.” He pointed to a long table set on a pedestal above the throne. At it were seated Prince Cleo’s seven cousins, four sickly girls and three weak, simpering boys. The heads of the princess and princes seemed hardly able to support the weight of their crowns. Behind each, a magistrate stood, wearing a heavy golden chain. At the head of the table sat the witch, smiling darkly. Behind her, in an attitude of fear, cowered Queen Mischa.

“Cousins,” Prince Cleo declared, for he had gone to the table already. “Our moment has come. Our fathers the Kings depend on us to resow the crops. To rebuild the granaries. To bring prosperity back to our people.”

“Many decisions to be made…” one of them muttered, while a magistrate whispered into her ear. “We must consider that the people are so very tired.”

“We cannot ask too much of them,” another said, appearing to repeat the words of her own magistrate.

“But work they must!” cried Prince Cleo.

“There must be equity. For on this side of the Twin Kingdoms, we are righteous,” another cousin answered, taking a sip from a vial of potion that lay before him. “Whereas your mother chose to let many die, we bear the responsibility for those who have lived and must now be kept safe.”

“And because your half of the Kingdom is strong. You must come to our aid,” the witch spoke at last. “For here, on our side, we cannot sustain ourselves. Ever have the Twin Kingdoms acted as one. You must start by rebuilding the bridge, so that grain can be brought in aid of our sick and our weak.”

Now the witch had lost her unnatural sheen and her pale face peeled away into yellow scabs. Prince Cleo grew angry at the sight of her. “By whose authority do you dare address orders to a Prince, you withered hag?”

“By the authority of the king!” It was King Tharm who spoke these words, roused from his throne below the Council Table. Prince Cleo looked to the table and saw now that each of his seven cousins had before them a vial of potion, from which they constantly took little sips.

“Be merciful nephew,” Queen Mischa spoke timidly, “Without the aid of her magic, they would soon die. She commands us now.”

Prince Cleo was enraged. His strong body flew into action, drawing a great long-sword from its scabbard. But as he lifted the blade to cut the hag’s head from her shoulders, his father the King stayed his arm and led his son away.

King Cleo and Prince Cleo sailed from the Left Kingdom back to the Right. The bridge was never rebuilt and the two Kingdoms grew ever apart – the Right one grew prosperous and stronger; the Left one slowly died, being sickly and false.

The worst lies are a mosaic made of a thousand truths

We live in a world of noise. Information, almost infinite, is streamed at us relentlessly, bombarding our minds and overwhelming our capacity to distill truth. In such a world, it is very easy for narrative weavers to create truth. After all, there are facts everywhere, enough that they can carefully select the ones that suit their message and create a story that is not only convincing, but is actually full of true facts. The lie is in the selection of facts, and the choice to omit ones that do not serve the narrative.

And yet… I believe with even a modest degree of focus, most of us would be capable of separating out the informational wheat from the chaff. I think we could know more truth with a bit more effort, if we really had to. The question is, how can that be done?

The Oracle and the Glock

This takes me to the ‘Oracle and the Glock’. One imagines an omniscient personage – for the sake of visualisation a faceless, spectral figure dressed in black body armour with empty, luminescent blue eyes, in the fires of which glows the flame of perfect knowledge. This is the Oracle. She is armed with a Glock 9mm pistol, black to match her general appearance.

Her M.O. is that she approaches you and places the barrel of the pistol against your temple. She then asks you a question; a question to which she, in her omniscience, already knows the correct answer. The game is quite simple. If you give her this correct answer, you live. If you fail to answer or you answer incorrectly, she will blow your brains out. But because the Oracle has some sense of justice, she will allow you enough time to scroll through the internet in search of whatever information you need to support your answer.

The question is this: In such a world, would more people come closer to the truth than is currently the case? In other words, how much is the plague of disinformation a result of willful ignorance, laziness and dishonest self-interest, and how much is a genuine artefact of the digital age, or the pernicious activities of Russian bots?

Who has Dominion over election results?

Perhaps it helps to consider a concrete example. Let’s take, for instance, the results of the 2020 US Presidential Election, in which Joe Biden is said to have defeated Donald Trump. Imagine the Oracle asked you this question, “If the 2020 election had been run entirely absent electoral fraud, mail-in ballot stuffing or manipulation of electronic voting machines, would Joe Biden still have been declared the winner?”

If you are a left-leaning, college educated Coastal American or a middle class European, you would casually answer this question with a ‘yes of course’ while sipping a £10 craft IPA with your friends on the sunny terrace of a trendy London bar. But imagine the question came while you were in the Oracle’s dark crucible, on your knees, transfixed by the piercing blue light of her spectral eyes?

I hope you would at least take the time to go through the evidence carefully – after all, the Oracle is patient. I hope the pressure of the Glock’s cold steel against your temple would make you just a little distrustful of the first few hits you got from Google. I hope you would dig a little deeper. You might think, ‘obviously the election wasn’t rigged. But, well, what if I’m wrong?’. Maybe you would dig out the footage of the vote count in Cook County or Philadelphia and look, really look, at what happened around 11 O’Clock that evening. Maybe you would listen, for the first time, to what Trump said that night and the next day and search for the lie in his eyes. What answer would he give to the Oracle? And if he really believed it was rigged, is he just a crazy, egotistical old man? Or did he know something I don’t? Maybe you would read the documents submitted by the Republicans in all the court cases that were dismissed for lack of standing.

You might even listen, for the first time in your life, to what intelligent people on the other side think is the right answer to this question. Not because you necessarily agree with them, but because there’s a chance you might be wrong. I certainly hope you would search for the truth, as if your life depended on it.

Because I know I would.

When I was a child, I liked to draw maps. Even at an early age, I understood there was something powerful about the ability to render graphic representations of spatial relationships on paper. From memory, I drew maps of the United States of America. It didn’t take me long to realise that if you memorised the big ticket contours (the point of Maine, the rough bulge of the mid-Atlantic, the curve and hook of Texas…) you could supplement this rough shape with random but detailed ‘squiggles’ that would approximate the twists and turns of the actual coastline.

To the casual eye, the map would look much more accurate that way. I recall some of my teachers’ reactions to these visually appealing, detailed maps of the US which decorated the blank pages of my phonics workbooks – they took me for some kind of prodigy. Of course, if you were to compare the detailed squiggles with the actual contours of the coast, there would be no more overlap than what chance might throw up – after all, I improvised the squiggles randomly. But it didn’t matter, the pretense of detailed knowledge was enough to convince most people that the map was far more accurate than it really was.

Would that this little deception remained in the workbooks of a 1980s schoolboy. Alas, this technique of pretending detailed knowledge has since gone mainstream. It defines ‘the Science’ behind a great many, drastic policy choices that are being implemented at this very moment.

Consider the Imperial College Model developed by Neil Ferguson, and which was adopted and copied to provide justification for draconian lockdown policies across the globe. The ‘model’ is very detailed and provides point estimates to a high degree of specification on how different policy choices would impact mortality as the pandemic progressed. The problem, of course, is that these estimates fell well outside the confidence intervals that should have been attached to them. If the fake squiggles had not been included in the model, the real answer would have been ‘we simply don’t know how many lives could be saved from locking down’.

Now, three years later, we can compare the fake Imperial College map with the actual evidence and we see how wrong they got it. Estimates for how many deaths would arise in the absence of lockdown were at least an order of magnitude wrong.

The same trick is being used to justify unprecedented changes in energy policy. Point estimates are being provided for the relationship between greenhouse gas emissions and increases in surface air temperature, with a degree of precision that completely belies the actual level of confidence ‘the Science’ could have in these numbers. In fact, as I argued previously, it is not possible to know whether the changes in climate the Earth is currently experiencing are at all the result of an increased concentration of GHGs in the atmosphere, because the two bigger causes of atmospheric heat – solar irradiation and albedo – cannot be measured with the requisite degree of accuracy, much less do scientists have any idea of the dynamic interaction between the three effects.

Of course, the really big problem with the pretense of detailed knowledge is that it acts as an obstacle to the pursuit of real knowledge. Once I became adept at faking coastal squiggles, I stopped looking carefully at the outline of the actual Atlantic / Pacific coasts, because to do so would jeopardise the professed accuracy of the maps I already drew. The same is true for climate science. No one is spending time and money to figure out whether the intensity or composition of solar energy is changing in a way that would impact the climate, because the question has already been answered, and the Science is not a very humble religious institution.

The question now facing us is whether we, as a civilisation, are prepared to do better than a bored 8-year old sitting at the back of the class.

This is a rom com musical feature film I have been working on together with my daughter Anna. The first piece of finished animation is hot out of the oven (literally, because the Indian guys who did the animation have had to deal with a heat wave in New Dehli).

There’s also a GoFundMe if folks want to check it out, share and like and subscribe and pray to the tech gods….

Before Covid, I had a high degree of confidence in the scientific consensus around climate change – i.e. I believed the scientists who said that climate change was real and was primarily caused by human activity. I even read some of the IPCC policy summary documents – notably this one. My faith in science-flavoured policy institutions like the IPCC was in large part owed to my status as an educated, middle class person, with employment and a social set in the same milieu.

It took Covid, and the destastrous string of wrong-headed policy decisions that followed – from community masking to lockdowns to vaxxine passports – for my faith to be forever shaken. I have filed for divorce from ‘the Science’.

What does ‘the Science’ really say?

And so I have now re-read the policy summary, with a more critical eye. When I do so, it’s quite shocking how weak the evidence for anthropogenic climate change actually is, and to which lengths the rapporteurs go to mislead on the strength of the evidence. Essentially, the evidence for greenhouse-gas driven climate change boils down to:

So that might look like a slam-dunk case, until you think about what is really being said – and what is ‘not’ being said. Sure GHGs can have an effect on surface temperatures, but what else causes radiative forcing? Three things, it turns out, and the least important of them is GHGs. First on the list – and this should surprise absolutely no one – is the heating effect of the sun (Solar irradiance).

The glowing hot Elephant in the room

Essentially the sun is the reason why we are not a barren, icy rock floating in space. The magnitude of the sun’s energy is so great that if it were to be switched off, the average surface temperature on Earth would fall to -17 degrees celsius in just a week – almost all life would be extinguished. Within a year, it would be -73 degrees, an unimaginably cold temperature.

The IPCC report makes a brief mention of Solar Irradiance, suggesting a positive change in SI contributes only minimally to global warming, essentially because the amount of variation is thought to be very, very low. The problem here, is that, given the size of the effect of solar irradiance, even small errors in the measurement or composition of the sun’s energy can overpower the effects of greenhouse gas concentrations in determining overall temperature change – by an order of magnitude. So a really KEY question in all of climate science must be, how accurately can we measure solar irradiance?

Sceptics will not be surprised to discover that the answer is, in fact, ‘not accurately at all’. This very readable Nature paper has all the details, but the upshot is that you can’t really measure SI from Earth, because the atmosphere gets in the way. You can try to measure it from space, but unfortunately space also gets in the way – high-energy particles, outgassing and optics damage all mean that the data has to be ‘adjusted’ to create anything like a time series. A number of space-based measurement exercises have been undertaken, starting in 1985, but each with different techniques and equipment. In other words, we have no idea if the amount of solar irradiance has been increasing or decreasing over the time period in which the climate on Earth has been warming.

Omitting albedo from the models reflects badly on ‘the Science’

The second most important cause of radiative forcing is albedo, or ‘reflectiveness’. The more reflective the Earth’s surface, the more sunlight ‘bounces’ off the planet and goes back out into space. The less reflective, the more sunlight is absorbed and turned into heat energy when it hits a terrestrial surface. Some surfaces are very reflective – like deserts, snowscapes, still lakes and the tops of clouds. Others are less reflective, like forests, urban environments and oceans. Needless to say, constructing a model with anything like accuracy that takes these effects into account is a data scientist’s worst nightmare – the risks of model misspecification or data error are enormous. In fairness, ‘the Science’ doesn’t even claim to understand clouds, much less cloud albedo, because they know that we all know how rubbish the weather forecasts are one week out – not to mention fifty years out.

The IPCC report does mention albedo as an offsetting effect in relation to aerosols, but fails to provide context as to just how much uncertainty there is in taking account of these effects. For example, how much does global warming increase cloud cover? Or: is deforestation increasing albedo and contributing to cooling? What about desertification? Not covered by the IPCC because the answer is, they simply don’t know.

The big point here is: if you are going to include radiative forcing in the model for the GHGs, you need to consider all the ways in which the Earth’s atmosphere gets and retains heat. Otherwise, what you are left with is a casual correlation between an observed increase in temperatures and a rise in GHG concentrations since pre-industrial times. We are reminded that correlation is not causation.

Is global warming causing GHG emissions?

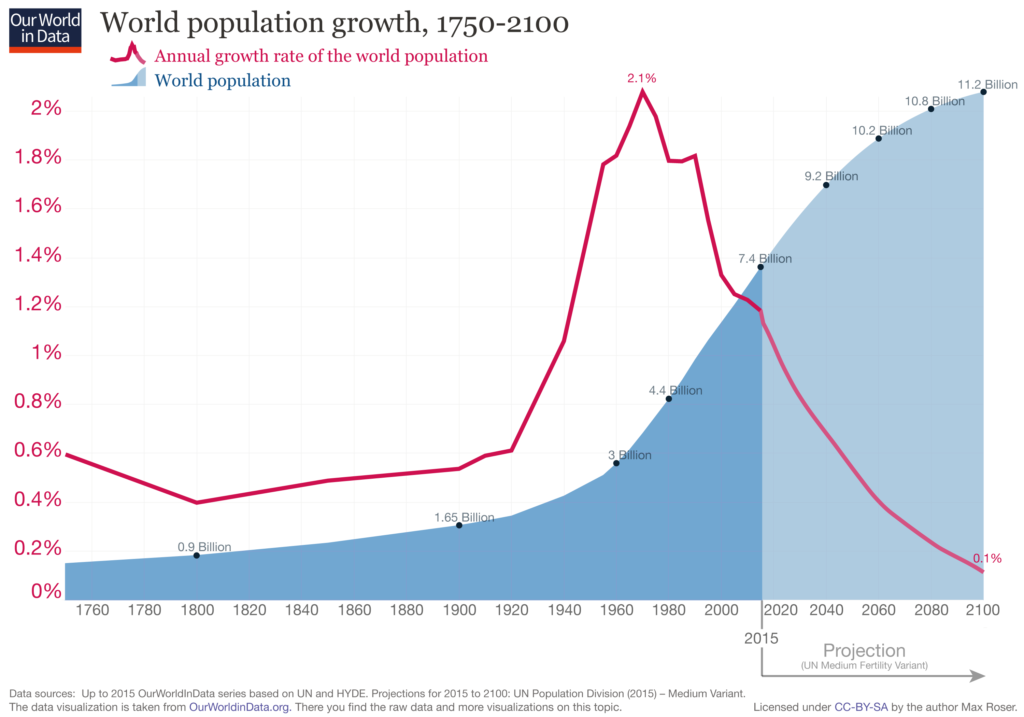

For one thing, it may be the exact reverse. We see increasing temperatures from 1880 onwards, and this corresponds pretty neatly with an increase in global population.

Just compare the two graphs above, and pretend you knew nothing of the ‘climate change consensus’. Would it not make sense to say that (1) the earth starts warming (due to, say, increased solar irradiance), (2) more heat makes the planet more livable for large animals like us, so our population goes up, and (3) with more of us around, we burn more fossil fuels making CO2 and trace gases in the atmosphere rise?

It might seem like hubris that I – who has never studied atmospheric science or indeed any hard science – should dare to think I could understand these phenomena better than the many bright researchers whose business it is to do just that. The fact is, I actually don’t consider myself any smarter than all of these people, and certainly not the best of them, and in an ideal world, I wouldn’t have to even try. The lessons from Covid, however, is that there are three good reasons why all the climate scientists could form a consensus so wrong-headed that even humble Graham can formulate a clearer understanding:

Undiagnosed irrationality.

Human beings are deeply irrational, a fact which societies of the past understood and made a functional part of their world view. There is no zealot more dangerous than the one who believes that he is above belief. Whereas a hundred years ago, most Christian priests understood that the spiritual realm was defined along a separate axis to the scientific one (and respected that other realm as distinct from their own), the condition of ‘the Science’ today is that its adherents are unaware of their own proclivity for myth-making. They treat articles of faith as if they were fact, because they lack a place to safely park their own irrationality.

This creates a dangerous culture of cognitive bias. Dogma, by its nature, is beyond questioning. We saw this clearly in Covid, where many scientists and doctors were afraid to challenge the ‘safe and effective’ mantra. Even today, with excess deaths for cardiovascular disease continuing at unprecedented levels, the mainstream cling to an irrational belief in their vaxxine theology.

Post-modernism.

The lumping in of climate anxiety with other tenants of contemporary ‘woke’ orthodoxy, such as trans-activism or critical race theory, is a favourite trope of the right. Yet, there is something to be said for the role of post-modernism in all of these trends. Post-modernism is the philosophical belief that reality is a social construct and therefore independent of objective truth. I and others have argued that this belief flourishes in developed countries today because so many people have been freed from the immediate constraints of the physical world by the luxury of their well-catered urban lifestyles. It is precisely here that we have a tie-in to climate activism.

Much of the ‘science’ around anthropogenic climate change reposes on an assumption that humans possess absolute mastery over the physical world. If you are an apartment-dwelling urbanite for whom food comes from a restaurant or an express supermarket, and water comes purified out of a pipe or a plastic bottle, you could be forgiven for believing this to be true.

Therefore climate activism, as a faith system, reposes on the idea that ‘we’ have the power to change everything, including the temperature of the planet. The idea that the massive ball of heat in the sky above us, infinitely more powerful than anything we could ever produce, is the true master of our climatic fate, goes against this world view, just as it is anathema to post-modernism that you are born into a sex, which is determined by God/nature and is immutable. How easy, therefore, to downplay the role of solar irradiation (outside our control) in favour of GHGs (something we can control).

Overeducation.

Simply put, academia is not what it used to be, back when only a handful of really smart people got to do it. Not alone does mass access to higher education reduce the average IQs of those with university degrees, I have argued that the very process of educating someone beyond their cognitive abilities leads to a reduction in their capacity to engage in critical thought. Increasingly, the scientific consensus to which the IPCC and policymakers like to refer, is created among these very people whose qualifications are not a result of intellectual merit, but rather is owed to the fact that, at age 18, they had both middle class parents and a distaste for any kind of manual labour.

Critical thought is beyond them. Even where the predominant ‘Science’ is patently in error, these young overeducated bourgeois lack the mental faculties and the tools to challenge it. What kind of a consensus are they likely to form, and why on Earth should the rest of us trust it?

I remember seeing the comedian David O’Doherty in the Fringe a number of years back. He had a great number on how a lot of rhyming expressions that seem profound are really stupid if you think about them, but the rhyme somehow makes them seem true.

It’s a lesson for how easily we can be misled by sophistry into believing false arguments, and points to the dangers of charming and gifted rhetoritians who shill for powerful interests. They can be funny, they can be convincing, but that doesn’t make them right.

My dear son,

We are in the final week of Lent, the period in the Christian calendar in which, according to the Gospel, Jesus crossed the desert to come to Jerusalem, where he would sacrifice himself for our salvation.

Lent is a time to reflect and look inwards. To pause and think about the journey we are on. When I do so, I always think about you Daniel. I think about the years we have not been able to spend together, all the things I would have taught you and the fun we never had together.

But more than anything, I reflect on the future. Lent will not last forever. One day, Jesus came out of the desert and walked into the city. People laid palms at his feet.

Maybe, one day, you and I will get a chance to meet and to know each other. You might find out that I am not such a bad guy after all.

I pray that it will be so.

Love,

Dad

Empires do not fade in a day. If you asked a British citizen when exactly their empire collapsed, they might point to the 1947 announcement of withdrawal from India, the British Empire’s crown jewel, as the landmark moment. But in reality, this merely formalised a shift that had been underway since the 1919 Government of India Act, the granting of home rule to the Irish Free State a few years later, and a whole host of other concessions the island rulers were forced into making as their economic and military power declined. By the end of World War II, the Empire had ceased to exist in all but its name, and in the collective consciousness of those old colonels living in a run-down seaside hotels, telling tourists about the time they hunted the Bengali tiger.

A hundred years later, the same might be said of that Empire known by euphemisms like – ‘the Western World’, the ‘liberal world order’, or my personal favourite: ‘the International Community’ – but is, in reality, better called the American Empire.

Not without some irony, Lingchi, the Chinese death by a thousand cuts, best describes what has been happening to this Empire. Cultural narratives like critical race theory and transactivism are tearing apart the Empire’s collective sense of self. As counterculture movements they are divisive by design. On the economic front, the steady offshoring of manufacturing capacity and the overeducation of a whole generation of unproductive soy-infused urbanites has left the Empire economically reliant on its favourable global terms of trade in order to maintain high standards of living among its ruling classes in the Coastal USA and in Europe. The legacy financial architecture, in the form of the petrodollar and the Bretton Woods institutions, grows shakier with every passing bank bailout. The ill-advised choice to politicise the SWIFT global payment system further erodes those financial foundations. At the same time, the self-hating ideology of climate activisim not only undermines the Empire’s own energy supply, but also heralds a steady attack on its productive capacity. Europe is about to ban combustion engine cars, a technology in which it maintains a historic advantage, in favour of battery-powered ones where it is forced to compete with China on more level terms, and where it is completely dependent on imported raw materials.

What, then, remains of the Empire and its ability to enforce its system of goverance on its global dependents? There is still some measure of political and cultural good will. While not entirely guiltless, this Empire has been more benevolent that many that have come before it, and American cultural exports like McDonald’s and Hollywood have made the Empire’s mass culture seem both accessible and aspirational. But I would argue that this good will has largely dissipated. Since Covid at the latest, the Empire is no longer a good ambassador of its own liberal values, if indeed it ever was. Hollywood has eaten itself, and Wokeism is a singularly unattractive cultural export for those in the far reaches of the Empire who feel neither guilt for American slavery, nor a desire to blur the gender divide between men and women.

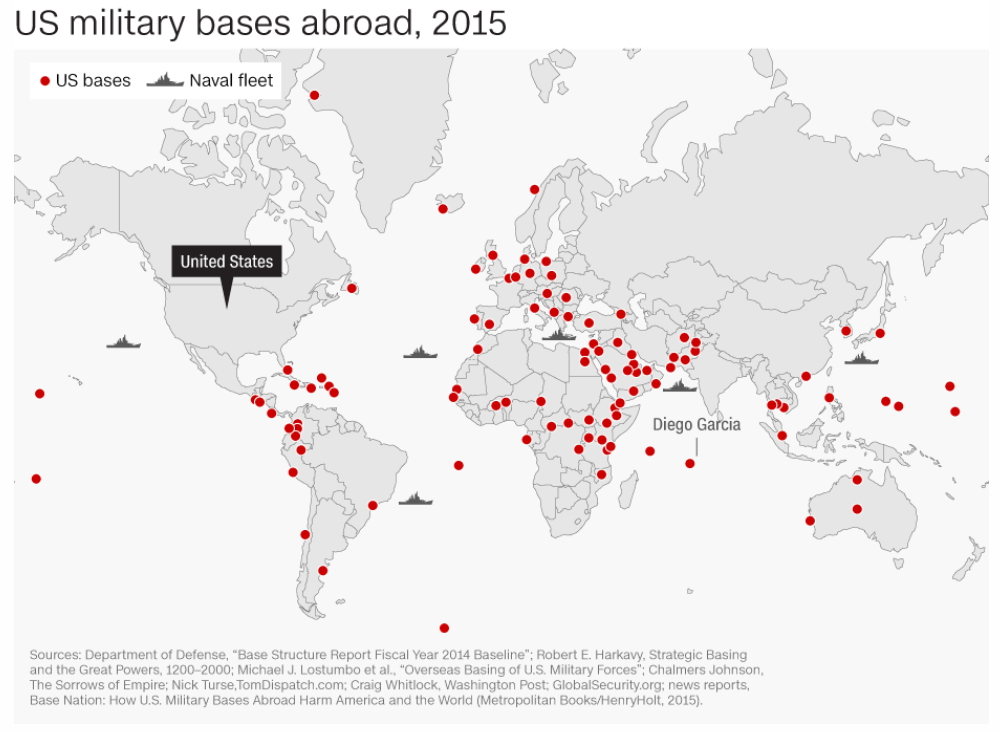

What the American Empire still has, of course, is the world’s mightiest military – effective control of international shipping lanes, satellite communication and a network of bases that neatly spans the globe. But the world is big, and as the map shows, there’s an important gap in the Empire’s coverage, right where it matters most. With the exception of volatile Pakistan, the withdrawal from Afghanistan has left the Empire with virtually no foothold on the biggest and most valuable continent: Asia.

In fact, on closer inspection the Empire’s military grip is tenuous. Sloth in the military industrial complex and avarice among the Empire’s European vassal states have hollowed out its real fighting capacity. For the most part, the Empire rests on its historical reputation and on the fact that its adversaries lack coordination. The fear of American power – rather than the reality of its execution – has, up until now, been enough to deter any meaningful resistance.

In this context, the breakthrough success of the Indian film RRR gains new significance. A smash commercial hit for Netflix, the three hour Tollywood blockbuster tale of friendship and revolution in 1920s occupied India enchanted audiences well outside of Hindustan. That the navel-gazing, ultra-woke Hollywood Insiders chose to shower Oscar recognition on it is less important than the fact that it was watched – and loved – by the Empire’s ordinary subjects, just as much as by the barbarians outside its borders.

Because RRR is not an Indian imitation of a Hollywood film. It is unwaveringly, unflinchingly and unashamedly not Western. With its cinematography, its over-the-top choreography and its Hindi-language in-jokes, this film makes no attempt to appeal to Western audiences. Its global success is the proof that today, that is not even a requirement.

Most shocking is the depiction of the Westerners. The British colonial occupiers in RRR are not just ‘bad guys’. They are depraved, morally bankrupt and palpably evil. The only redeeming Western character is Jenny (Olivia Morris), the white woman who falls in love with the dominant Indian protagonist, and who finishes as a happy bride, dancing in a sari and singing in Hindi, unphased by the brutal annihilation of her wicked family and loss of her Western way of life. The message is clear: we’ll take their women too.

Yet that is not the worst. Nor is it even exceptional – after all, unflattering depictions of the West have been common in Western media for decades. The truly shocking thing about the British villians in RRR is that they are weak. Physically, morally and intellectually weak. They recoil as cowards against the righteous outrage of the Hindi protagonists. They cannot shoot for beans and they lack the physical strength of Indian men.

Whether this is an historically accurate and fair depiction of the British Army during the Raj is entirely beside the point. What matters is that in a global blockbuster that out-eyeballed all but a handful of Western films last year, the Indian director feels empowered enough to depict the West as hopelessly weak. And barely anyone bats an eyelid. India’s foreign minister even used the representation as a barb, in conversation with the American Empire’s foremost disgraced lapdog, Tony Blair.

A few months later, the world witnessed the spectacle of Presidents Xi and Putin embracing each other during a state visit to Moscow with a display of friendship and complicity that left little doubt about their intentions with respect to the American Empire. Neutral spectators from Latin America to Africa, to the Indopacific are watching. And now, they are no longer sure the West can contain this new Asian Axis. With emergent Hindi nationalism as a tailwind, and given the subcontinent’s historic links to the USSR, there is no guarantee that India will heed the American Empire’s warnings not to slide too far into a Putin-Xi rebel alliance.

After all, as RRR has shown, the world may have less to fear from weak, evil Westerners than the US State Department would like them to believe.