Haunts of the Black Masseur: The Swimmer as Hero by Charles Sprawson My rating: 3 of 5 stars

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

I don’t read a lot of non-fiction. I find much of it to be clunky, badly organised and badly written. It favours substance over form, as if there were ever a trade-off between the two! Non-fiction tends to pay little attention to the beauty and flow of words and sentences or the cadence of ideas. Worst of all, it lacks kindness to the reader. As in, ‘if you want to know what happens, mate, you will be forced to suffer through my clunky prose’.

At first glance, Sprawson’s watery account of the literature and history of swimming and all things wet appears to be no exception. By page 100, you realise you have been thrown in at the deep end of a self-indulgent pool of random facts, written by a man whose sole purpose in authorship is to free his head of as much aquatic trivia as he can, so that he might go back to his preferred lake or river and have another dip. Sprawson doesn’t even attempt to adhere to his own loose chapter structure – to wit, a big chunk of the final chapter, which purports to tell us about the decade Japan dominated competitive swimming, veers off into an impossibly long tangent about the effeminate French writer André Gide’s favourite Gallic watering holes. The hook is that writer Yukio Mishima liked Gide’s work.

But beneath this eddied surface, Haunts of the Black Masseur has hidden depths. The very self-indulgence that defines his writing style, is mirrored in the book’s theme – the swimmer is submersed, alone, embraced by nature, without the lifeline that tethers us to bourgeois morality. The point is, he does not have to be coherent, sensible or clear. He is free. This is the Masseur’s common current; the love of swimming as subversive counterculture or escape, which binds Ancient Greece, the English classicists of the 18th and 19th Centuries, the German Romantics, the Americans and finally (if only briefly) the Japanese.

So if you are prepared to forgive Sprawson his contempt for good writing and allow yourself to be swept up in a riptide of delicious, random and sometimes surprising anecdotes, you may just reemerge from the experience refreshed.

View all my reviews

Author: Graham

My Christmas letter to you, 2024

Dear Daniel,

Merry Christmas! I hope that through the gloom of the dark winter the joy of Christmas is shining brightly upon you.

I have always loved Christmas, for many reasons. First, because it is the birth of Jesus, a baby who comes into this world to give us new hope and to save us from our sins. I believe that even those who are most sinful can find a path to justice, and Christmas is the start of that path.

But I also love Christmas as a pagan holiday. It is perfectly timed, just after the Winter Solstice (December 21st), to symbolise the time in the year when the days are getting brighter and spring is coming (the ‘Yuletide’). You can’t feel it, but it is coming, and the world will be renewed again!

Finally, I love Christmas because it is a time for family to come together. Of course, in your case, it means I miss you. But it has been nice spending time with your sister Daphne. And I hope you have been loved and have been able to love this Yuletide.

So Happy Christmas, my lovely son. I love you,

Dad

A simple plan to stop the killing in Europe

Donald Trump has won the election, in part on the promise to bring an end to US involvement in foreign conflicts. This includes swiftly bringing an end to the war in Ukraine. But how?

Here I propose a simple and, I think, obvious solution to the conflict that could be acceptable to all sides.

Main elements of the deal

- An immediate ceasefire along all lines of contact, and for all missile and drone attacks.

- The Russian Federation withdraws its forces from all DMZ territory currently occupied (e.g. the city of Mariupol…), and relinquishes all territorial claims to Zaporizhzhia, Kherson and Kharkiv oblasts.

- Ukraine withdraws its forces from Kursk and any other territory of the UN-recognised Russian Federation. Ukraine withdraws its forces from those parts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts currently occupied by AFU forces. Ukraine relinquishes any legal claim to Crimea, Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts.

- Ukraine is divided into three regions, as below, (for which all parties agree to seek immediate recognition by the UN):

- The first region (in dark blue on the map) is the EU security zone. This comprises all oblasts and parts of oblasts west of the Dnieper River. The only territory east of the Dnieper is the remaining piece of Kiev Oblast. It is understood that this region will fall under the protection of NATO, as it transitions into a permanent security arrangement under a new EU Defense Treaty, which would have a smaller and decreasing role of the United States, but would cover countries like Moldova, (Western) Ukraine, the UK, the EU itself and other areas vital to Europe’s security interests.

- The second region (in light blue on the map) is the DMZ. This region comprises the Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, Kharkiv, Poltava, Sumy and Chernihiv oblasts, as well as those portions of the Cherkasy and Dnipropetrovsk oblasts that are east of the Dnieper River. It remains under the administration and jurisdiction of Ukraine, but is not covered by the EU Defense Treaty. Ukrainian police can operate, but no weapons systems, artillery, combat units, military aircraft or missiles are allowed. Russian military advisors have permanent, unfettered access to all parts of this zone. All civilian and economic infrastructure remains fully Ukrainian, with no obligations to supply or facilitate the supply of power, water or other utilities to the Russian Federation.

- The third region (in red) is Crimea including Sevastopol, as well as Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts. This territory becomes part of the Russian Federation.

- The Russian Federation grants freedom to navigate in the Sea of Azov for all civilian and commercial purposes and allows unfettered access through the Kerch Straits.

- Ukraine commits to passing, in law, denazification rules, in particular in relation to the Azov Brigade and a full repudiation of historical associations with the Nazi German SS.

If karma’s a bitch, coincidence is a rabid she-wolf in heat

Our brains are programmed to seek patterns, even in the wildest storms of chaos. Imagine the universe spitting stars across galaxies, in a physical process that literally bends time, as close to perfectly random as possible. Now imagine standing on a rock in the middle of all this and looking up at it. What do we see? A connect-the-dots picture of a hunter with a club and a belt; a saucepan; and a giant bear.

Assuming the universe truly is random, why then do we indulge in this kind of silliness? It must serve some evolutionary purpose for us to believe in patterns, in fate, in a hidden intelligent design behind the apparently random.

Maybe ideas like karma evolved because they can help us to curtail psychopathic tendencies, by fostering in us the belief in some external enforcer of socially desirable behaviours. Once comforted by such a belief, the very idea of pure coincidence, of random outcomes behind which there is no deeper meaning at all, can provoke an almost existential level of angst – that moment when atheists stare into the abyss of their own belief systems and recoil in horror.

If God truly does exist, I am sure He create the concept of randomness and its bastard child coincidence with a very specific purpose – to scare the shit out of anyone foolhardy enough not to believe in karma.

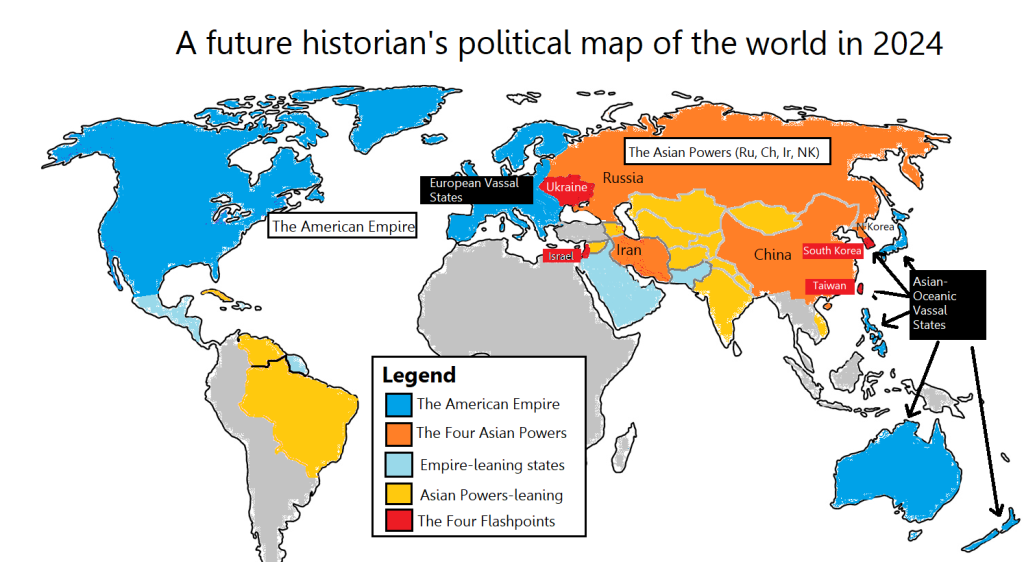

A future historian’s map of 2024

Chapter 24.1 – With 20/20 hindsight, 2020 will be crystal clear

Sometimes it’s only possible to understand what is going on with the benefit of hindsight. Think of your own traumatic childhood – after all, we were all scarred horribly by our childhoods (at least, all the interesting people I know were). Yet at the moment when the worst events were happening, how aware were you of the full context? I remember the moment my family fell apart – I was eleven and my biggest concern was not the loss of my parental relationships, the long and ugly court battles that lay ahead, the loss of a nurturing home environment or the economic hardship that would follow the disorderly dissolution of family wealth. No, it was the loss of my pet turtle. Now, 38 years later, I can’t even recall that turtle’s name.

And what is true of family histories is as true of our greater political history: We turn on the news and are bombarded with images of … ehem … bombardments. The news item changes, and we are being told by some talking head or other that this US Presidential election is the one that really really matters – not the last one we were told really really mattered. But are these the ‘world-changing’ events really that big a deal? How will future historians see the things that raise eyebrows, like Russia invading Ukraine or Israel attacking UN peacekeepers in Lebanon? Will Julian Assange make the Table of Contents?

Chapter 24.2 – Citing foresight, for four poor sites?

Given what we know about the folly of making predictions when you’re caught in the storm of current events, only a fool would attempt to answers these questions. I always remember that wisest of sages, my father, telling me as a boy in the 1980s that I’d better hurry up and go visit the Amish, before they all disappeared. Decades later, while on a trip to Upstate New York, I asked a local if there were any Amish left and was nearly laughed back to New England. “The question is are there any non-Amish left. They have like ten kids each!”

Or else consider a sage even wiser than my father: Francis Fukuyama, with his ‘End of History’. He predicted that the 1990s had already seen the end of global conflict – that economic liberalism and democracy had won and solved the question of how to rule, and that everything that would follow would be a series of internationally organised peacekeeping missions to slowly spread the joys of Westernism to the far corners of the earth.

Chapter 24.3 – A fool and his predictions are soon parted

Of course, I am every bit the fool my father and Fukuyama are, so I will attempt to do the impossible: draw a political map of 2024, as it might appear in the textbook of a future historian of, say, 2034. This is what I believe it would look like:

The first thing to notice about this map is that the United States of America doesn’t appear on it. That is because, in my view, the constitutional republic of the US will be considered by future historians to have ceased to exist some time in the mid to late 20th Century, (when Deep State operatives assassinated President Kennedy). Instead, there exists the great empire of the time, drawn in blue – the American Empire, whose capital is not Washington DC but New York City. It occupies the territory of North America, but includes two blocks of vassal states: one in Europe and one in the Asia-Oceania Region. There are a number of aligned states, most notably the region of the middle east, which I believe historians would simply view as being ‘occupied by the American Empire’.

The other great power bloc is comprised of the Asian Powers (Russia, China, Iran and North Korea), supported by their network of sympathetic Asian states (Kazakhstan, India, Vietnam…). Most of the developing world is in grey, reflecting their weak ideological alignment and susceptibility to economic or even military suasion from either of the two blocs.

Chapter 24.4 – The four forlorn corners of Asian conflict

The future historians will conclude by identifying Four geopolitical flashpoints – areas where the American Empire’s political and economic boundaries and interests brush up against those of the Asian Powers: Ukraine, Israel, South Korea and Taiwan. Simply put, the Asian Powers cannot afford to allow these regions to remain under the sway of the Empire, and the conflicts that will bring the blocs into outright war hinge on these four geographic corners of Asia. As the Empire declines, the future of the world hinges on the fate of these four flashpoints: if Ukraine falls to Asia, the ripple effect on the European Vassal States will be so profound it will unwind a goodly portion of the Empire’s Atlantic power. If Israel falls, the Empire will lose its grip on the resource-rich Middle East. If South Korea falls, the Empires North Pacific flank will collapse, and if Taiwan falls, the South Pacific will soon follow.

So much for Chapter 24. A part of me is burning with curiosity to turn the page and read Chapter 25. But another part of me wants to turn back to Chapter 0 and watch an episode of Friends.

Ode to Pride

Reclaiming science

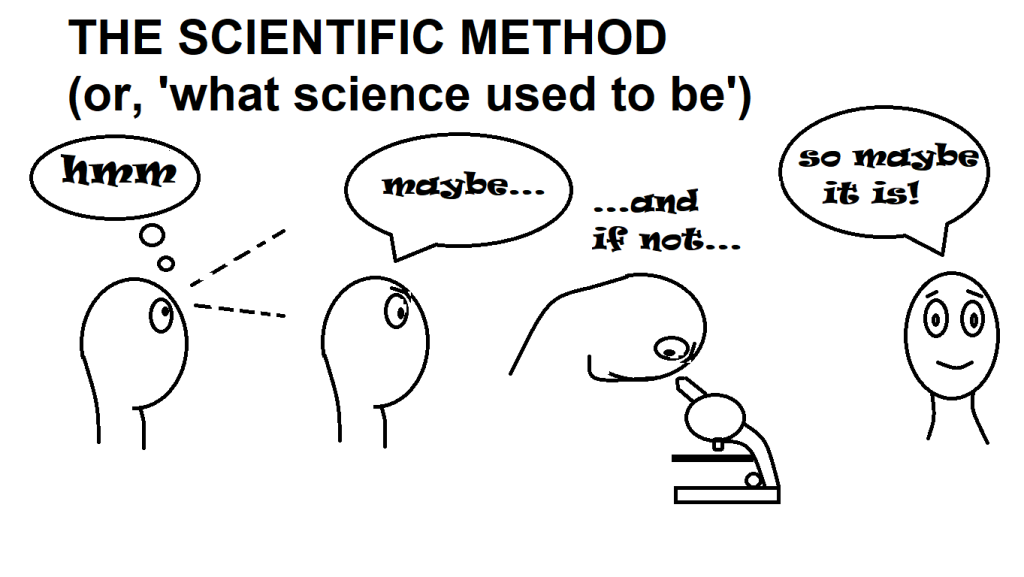

As the debate heats up, I find myself getting more and more interested in the politics of climate science. What is interesting is how lost the concept of ‘science’ has become in today’s society. To see how, we need a little look at the history of science. As far as I can tell, ‘science’ has gone through three distinct stages.

There was a method in their madness

To begin with, ‘science’ was a method. It was a way of thinking about how to solve problems, by formulating ideas and testing those ideas empirically to see if they stood up to scrutiny. The method was quite simple: you start by looking at the world, observing things and making associations. You smell, taste, see and feel your way around this universe. As you do so, you notice associations and patterns. Some could be meaningful, some could be coincidence. It doesn’t matter, you are ignorant but curious. Most of all, you are humble.

Next, you look at the associations that seem to make the most sense. You then formulate a hypothesis based on what you observe. This is a guess about the relationship between things you observe in the universe – does one thing cause another? Is there a pattern here? Is it likely to happen again? It’s important that the hypothesis is falsifiable – i.e. that you can think of ways in which, if the hypothesis is untrue, you can show that it is untrue.

Next, you test your hypothesis. The goal of testing is to prove the hypothesis wrong. You think of as many ways as possible that the hypothesis might be shown to be wrong and you test all of these ways. Remember, you are humble. Your goal is to prove yourself wrong, to rule out a false association, not to have your name put up in lights.

If, however, the hypothesis survives lots and lots of rigorous testing, we get to call it a ‘theory’. The longer a theory survives consistent critical scrutiny, the stronger the theory becomes, scientifically speaking. We don’t call it ‘truth’, but we imagine that by continuously and selflessly applying this method, over and over again, we can begin to approach the truth.

In these early stages, scientific journals were a useful way for scientists to share their findings. The peer review process formalized the shared interest in scrutiny. As real scientists, we welcome this scrutiny, because remember – as humble scientists our goal is to rule out bad hypotheses. The more scrutiny, the more we rule out falsehood. It’s like a piece of iron, getting hammered on a hot anvil, again and again, until it turns slowly into hardened steel.

From the ‘fields’ to the ‘silos’

This method was applied with varying degrees of rigor to many fields of inquiry. And with success, came a new Steel Age of Enlightenment. Slowly, over time, some of those fields became synonymous with the method itself. The set of disciplines is amorphous, but is usually thought to include the ‘hard’ sciences like physics, chemistry, biology, as well as some applied sciences, like engineering and medicine, and then bleeds into the ‘social sciences’ like economics, politics, psychology and… ehem ….sociology.

As the number of disciplines claiming some connection to ‘science’ grew, the rigor with which the scientific method was applied grew more lax, giving rise to the dysphemism ‘pseudo-science’ to describe disciplines that wanted to enhance their legitimacy by claiming an association with the scientific method, without actually having to apply that method to their work. This is in part the cynicism of academia, but it is also a reflection of a key limitation of the scientific method: the requirement that hypotheses be falsifiable. Particularly in disciplines where laboratory experimentation is not possible, disproving a hypothesis is hard. In social sciences, all you really have is population level data. You can try to be rigorous using statistical sampling techniques, but as Frederick Hayek points out in the excellent rap battle against Keynes, “econometricians are ever so pious. Are they doing real science, or proving their bias?”

And as the scope of academia balloons out with the expanding university educated middle classes, the corpus of ‘scientific’ literature must grow, even beyond the confines of useful experimentation and hypothesizing. More and more, dodgy population-level datasets are being drawn upon to produce ‘scientific’ findings. The scientific journals, once a convenient place for scientists to expose their work, are now little more than tools for would-be professors to build their resumés. Now we are already at the point where real scientists should start getting worried.

Follow The Science, for His name is Fauci and He is your shepherd

But it gets worse. Because not only are bloated universities and dodgy pseudo-sciences creeping in on our humble method, but somewhere along the line, we enter the third and final stage of ‘Science’, in which all humility is about to get polluted by something much worse than a middle class 28 year old who dreads the idea of having to look for a real job: the sinister influence of Big Money.

That’s right, the real attack to science comes not so much from the patched-sleeved tweed jackets of the sociology departments, but from the lab-coated back door of the applied sciences, and in particular from medicine. As academia expands, the game becomes about funding – research grants, partnerships, what have you. At the same time, as Big Pharma grows to become one of the biggest industries in the West, a set of government institutions and research agencies grows entwined with the business interests of these for-profit companies. Soon, the academics are indistinguishable from the editors of peer-reviewed journals, and from the revolving door between the industry-funded regulators, the government-funded Institutions that dole out research funding, and the industry itself.

This set of institutions has now developed a stranglehold on the peer review process. They fund the research, thereby setting the agenda. They have even created standards for creating evidence – including things like double-blinded randomized control trials – which only they can afford to carry out. And when even those safeguards fail, they resort to the basest of tactics to suppress dissenting views. Remember, dissenting views are the very essence of what science used to be. Now we are treated to popular slogans like “I believe in Science”, pronounced by zealots who are too simpleminded or ignorant to appreciate the irony in that statement.

The climate around science needs to change

This is all regrettable, but not momentous in a world where this ‘science’ remains contained in the lecture halls and laboratories. But of course, it does not and cannot content itself with that.

It leaks out of the lab and into the very real world we are all forced to inhabit, bringing us things like lab-engineered viruses, and the whole host of harmful and ineffective responses to the problems this ‘science’ has created in the first place: social distancing, masks, lockdowns and novel, vaccine-like mRNA treatments.

But perhaps nowhere is the application of Institutional Science so dangerous as in the field of Climate Alarmism. The planet is in peril, don’t you know, and if we don’t Follow the Science, we’ll all burn.

But will we though? The first thing to note about Climate ‘Science’ is that it does not welcome any dissent or attempts to prove it wrong. Rather than being a steel theory, made harder by the pounding of many critics’ hammers, it is a fragile house of cards, built high and tall upon a tower of assumptions and modelled results. Any criticism is met with violent defence, like the overprotective mother of a sickly little child.

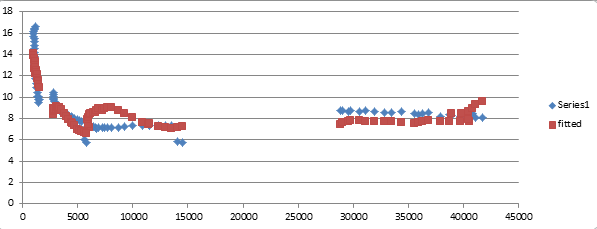

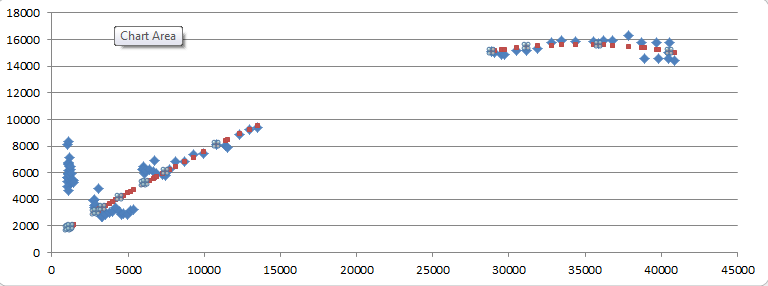

Those criticisms are many and obvious, so I’ll be brief in my enumeration: (1) lack of falsifiability i.e. what would it take to prove the climate theories wrong? Any temperature anomalies or changes are just retrofitted into the models and a new, even more dire, IPCC report comes out the next year. (2) model misspecification can anyone explain the relationship between the basic physics constants and the climate sensitivity parameters in the models? What about missing explainers like cloud albedo, photosynthesis, solar irradiance flux? (3) measurement error – what is the temperature anomaly, really? How well are we controlling for heat island effects? How well are we measuring solar irradiance, for that matter? (4) Model invalidity – what about all the things the models didn’t explain before, like ocean temperature anomalies? If we don’t understand them, how predictive are these models really?

What we need to do is stop, take a deep breath and go back to the scientific method. Let me attempt to do that now.

I spy with my little eye something beginning with ‘s’

The first point here is that it is not arrogant or unscientific for a ‘lay’ person like me to attempt to look at the issue scientifically. If you go back to the original definition of science, in fact it is the very essence of inquiry: simple observation.

So that’s where I start. The first thing I notice is that indeed, it has been getting hotter. I have lived in many place in the Northern Hemisphere and talked to many residents of those places and one can indeed observe pretty big increases in temperatures across the hemisphere.

When I look in the sky, the thing that I observe to be making it warm is the massive ball of energy in the sky, so my first hypothesis would be: is the sun getting ‘hotter’, i.e. emitting more energy than before? I don’t know, but let’s call that hypothesis number 1.

Next, I think about the rock I am standing on. It feels like cold earth at my feet, but I know from going into mines that actually, that cold earth gets pretty darn hot pretty quickly when you start to dig down. In fact, it seems that the earth’s average temperature is not 17 degrees the way we think, but rather it’s something closer to 4,000 degrees Celsius. This matters, of course, because all that heat is constantly radiating up through the mantle and onto the surface, then into the atmosphere and into space.

Much of that effect comes through the oceans, which are closer to the hot core. So my next question would be, is that process very, very constant? What if changes in the diffusion of heat through the mantle were warming/cooling the oceans at a different rate? I don’t know, but let’s call that hypothesis number 2.

Next, I look into the night sky above my Belgian home and see something remarkable in the northern sky. Dazzling colourful lights. Beautiful. But also kind of scary. What’s going on? I’m told it’s changes in the magnetosphere, and that the magnetic poles are in a ten-thousand-year process of ‘flipping’. Could such disruptions in the magnetosphere impact the penetration of certain rays from the sun? I don’t know, but let’s call that hypothesis number 3.

Then there’s the burning of carbon fuels by humans. Millions of gallons of oil every day, and in ever increasing quantities. All the fuel creates heat of course, but that first-order effect might be small. However, perhaps this creates some emissions that change the composition of the atmosphere. Also seems to be a small effect, but let’s see. After all, I don’t know. So let’s call that hypothesis number 4.

Others might have more and better ideas. That’s fine too.

Now let’s work through our hypotheses one by one, trying hard to disprove them. And let’s see which ones survive the best.

My hypothesis on that? Given what I know about the monster ‘science’ has become, the best survivor is unlikely to be the scientific method.

My 19th letter to you

Dear Daniel,

I hope the summer is going well – despite the very mixed weather we’ve been having!

We’re making the best of it. The garden at home is struggling – I managed to harvest only about half the potatoes I thought I would, but it’s still a good result, given how much rain we had. The tomatoes (Jo is looking after them) are in a worse state, but that’s also because we went away for a week in May.

Right now I am in Ireland with your sister Daphne, who is with her friend Isidore doing a pony camp. We are in a place called Leitrim, a wild, beautiful part of Ireland where however it rains quite a lot! Isidore’s dad is cycling around Ireland as we speak (he’s a former champion cyclist) and his mom is working from the cottage next to me here.

I’m sad to hear that you don’t want to see me, and also that you are not interested in meeting Daphne, who talks about you all the time and is – frankly – determined to get to know you sooner or later. You will have a hard time not meeting her, I’m afraid, as she has a strong character and works busily at getting what she wants. (Sometimes that is a challenge, I can tell you!)

But most of all, I wish you well and send you my continued love. Please know that whatever happens, I will always be here for you, the day you decide to take the leap and get to know me.

Love,

Dad

On leaky woodsheds and subjective validation

I sometimes listen to Brett Weinstein on the Darkhorse Podcast, whence I hear an uncanny number of my own, older ideas echoing back at me – which is a little creepy, somewhat flattering but mostly not that edifying an experience. In general, I find Brett in that category of thinkers who – though quite smart and original – is slightly less smart and original than he thinks he is. If his brain were a little bigger, or his ego a little smaller, he would stand a better chance of making a meaningful contribution to the world of ideas. All in all, I think I listen more for the comforting and good-natured repartee he has with his sidekick wife Heather, than because I expect to learn something.

Occasionally, though, Brett hits upon something that really provokes thought. In a recent episode, he makes the point that there is a fundamental difference between academic and vocational education: for the former, test results are given by the teacher. It’s possible for the teacher to exercise discretion, induce grade inflation or act on biases. For the latter, the outcome of the education is too closely tied with a material, objective result. If you write a bullshit essay about the sociology of queer bubble tea drinkers, it’s possible a sufficiently biased teacher would give such an essay a high grade that does not reflect its true merit. If, on the other hand, you build a book case so badly that it falls apart upon contact with any reading material, there is nowhere to hide the fact that you have not been a good student. The physical world has a way of highlighting failures which, in the artificial world of academics, can be disguised behind a veil of ‘subjective validation’.

This idea of ‘subjective validation’ is actually an important point for making sense of the Western World in 2024. I have argued before that wokeness as a form of postmodernism is a real and meaningful concept for understanding current affairs – so many of society’s ills involve the replacement of the objective with the subjective. I have also argued that there is a pandemic of overeducation which leads to the ‘dumb but educated’ having less – not more – capacity to reason.

Weinstein’s point about education fits right in to this architecture. From kindergarten through to her second master’s degree, the entire life path of a middle class, professional American is defined by validation – not from the hard edges of bumping into physical failure – but from the soft, socially malleable constraints created by authority figures, peers or other social forces. Even in the physical sciences, the majority of ‘research’ involves models and theories that are two steps away from any practical application. This dulls us to the rigors of objective reality, in favour of subjectivism which may in itself be a defining factor in the success of postmodernist ideas like critical race theory or transgenderism.

None of us is immune from this, of course. I recently attempted to erect a woodshed in my garden. To accomplish the task, I took with me a few tools, but a much larger stock of hubris from my relative success as an ‘attender of meetings’ and ‘sender of emails’. After all, I have many degrees and accolades, etc, etc. None of this mattered much to the final result of the woodshed, which currently stands as a risible and leaky testament to the fact that the physical world doesn’t give a damn how smart other people tell me I am.

In fact, you can generalise Weinstein’s point to encompass many phenomena in today’s society; a society in which an increasingly large number of people have learned what they know through subjective, rather than objective, validation. Take the entire culture of safety-ism. If your conception of the dangers of falling and hurting yourself comes from warnings issued by your overprotective mother, rather than the crunch of your seven-year-old bones as you plunge from the climbing frame, then your understanding of risk is one degree separated from the consequence itself. How well equipped will you be when, later in life, the government mandates you to Stay Safe from a virus that poses virtually no risk to your 24 year old body?

And what impact does subjective validation have on the media? If the very idea of what is ‘true and correct’ comes, not from a careful observation of nature, but from some authority figure telling you ‘you are right’, what hope can we hold out for the journalists whose job it is to sort through this very social noise in search of the important objective facts? Today on Substack, the excellent Eugyppius writes about how shockingly the media has reported on the thorny issue of President Joe Biden’s mental health. When the quality of reporting is validated not by any objective truth, but rather by the subjective validation of the collective authority (in this case of the elites themselves), this kind of mistake will be par for the course.

Of course, the world of subjective validation is itself ultimately subject to constraints of the objective kind. When entire generations have been told they are smart and clever by indulgent university systems, the fruits of this false validation will eventually result in economic stagnation, in military unpreparedness, and in a lack of meaningful innovation.

In other words, the woodsheds we’re building are getting very leaky.

Papa Jack’s Café (title song) – Anna Offergeld-Stull

From the soundtrack for Papa Jack’s Café – the Musical, written by Graham Stull, arrangement by Stéphane Collin