Whether lockdowns make sense or not is an important question, and it is hard to answer definitively. Hard, for a number of reasons. First, as is often said, we do not have all the data at our disposal. On the epidemiological side, we are only just beginning to understand how the virus has been spreading and whether or to what extent lockdowns make a difference.

Quantifying the economic costs of lockdown

On the economic side, there is a large degree of uncertainty. While clearly the economic costs are large, there are inherent difficulties in untangling the costs of lockdown per se from the costs of the general COVID hysteria which would ensue, even in the absence of any government measures. And even then, calculating the costs of lockdown itself is tough. As economists are at pains to stress, this episode is without precedent in modern times, and given the extent to which Western economies have developed over the past fifty years, the older precedents such as WWII or the Great Depression, lose relevance due to the differences in how modern economies operate and the level of prosperity we have come to take as a baseline.

So we have to really try to go back to first principles. What have lockdowns done? As I see it, they have done two things to the economy. First, they have stopped production. Quite simply, governments have closed stores, factories, restaurants, bars, schools, etc., meaning there are fewer goods and services being produced by the economy. How much of the economy is now closed depends on the nature of the lockdown (France, Italy, Spain, Belgium, Germany, New York City, Michigan, Ireland…, are extreme examples; many other US states and the Netherlands less extreme, Sweden the least extreme), but easy estimates put the number at close to a third of the economy.

In some cases, production will have shifted from the formal to the informal economy: restaurants are no longer preparing food, but people are cooking more at home; teachers are no longer caring for and minding children, but parents are doing so at home, etc. However, in many cases, the production is simply being lost. Again, how much is the result of the lockdown and how much of the generalised COVID panic which would have occured anyway? It’s difficult to say, but to put the loss at 15% of the economy does not seem unreasonable, especially when we consider that the two are interlinked: people panic in part because governments lockdown.

The second effect is the productive efficiency loss. We can take teleworking to be less efficient that working in offices, as otherwise the economy would have phased to telework years ago. (After all, the technology is not particularly new and companies wouldn’t willingly fork out for prime office space if they could get the job done as efficiently with no rental costs.) Home schooling is also a large efficiency loss, related to scale diseconomies (a class of 24 formally taught by one teacher, is now being taught by 24 parents) and the fact that parents are not trained teachers. Supply chain disruptions mean that work stoppages occur even in otherwise unaffected sectors: E.g. construction companies cannot pop down to the local supply shop to get an extra bucket of 3″ screws). Quantifying these efficiency losses is tricky, especially because they may be partially offset by some efficiency gains (fewer useless meetings for people to sit through).

There is also, I think, a non-linearity here with regard to time. If we think of businesses as having both an operational and a strategic component, then the former can probably cope better with remote working for some time, and in the short term, a company can get by without a new strategy. But in the long term, the lack of face-to-face contact will make strategic decisions like restructuring, brainstorming, hiring and firing…, much more difficult. This means fewer new ideas, less innovation, less efficiency gain.

Finally, there is the economic impact of social costs. The harm to people’s mental health from isolation, the loss of emotional development for, in particular, vulnerable children. The scarring effects of unemployment and disattachment from the labour market for those who have lost their jobs. While these are all first and foremost social costs, they will also impact the economy through reduced output, higher crime and wasted human potential. Again, these are non-linear with regard to time: the longer the lockdowns go on, the more costly each added day of lockdown will be.

Quantifying all these effects is not easy. If we take as a baseline four months of effective stoppage, and assume this halts 15% of output, then countries in full lockdown can expect at least a 5% one-off loss to annual GDP from the first effect. For the other two, the effects are likely to be more drawn out, but less acute. Using the four-month baseline again, the efficiency cost of teleworking could be estimated using the rental value of the office space currently being leased. In the EU, there is an estimated 650 million square meters. At an annual rent of €400 per square metre per year, this makes about 90 billion in lost office for the 4 month period, or about 0.5% of GDP. Of course, this is a lower bound; it’s reasonable to assume, given the transition costs associated with the shift, that this number is closer to a full percentage point in GDP.

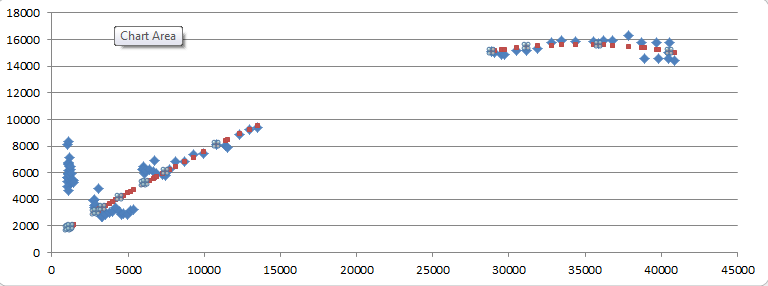

Next is lost productivity for parents. Here we can assume that working parents of dependent children suffer, as a result of the caring responsibilities. Data is available from Eurostat on employment rates of parents by number of children, the distribution of population by number of children. Combined with data on industrial annual earnings for the age group 30-39 (a proxy), we can estimate the lost productivity using wage data and assuming single parent households lose 50% of productivity, two parent households with one or two children lose 25% of productivity and households with three children lose 10% of productivity. (Households with more than two adults are assumed not to lose productivity). This amounts to another €90 billion for the 4 month period, another 0.5% of GDP.

Other costs arise from the stoppage of routine medical activity and the mental health toll. Here indeed, disentangling lockdown from baseline costs is tricky. Undoubtably, any alternative to lockdown would carry with it a certain mental toll, as well as an increased (albeit likely short term) demand on health services. Similarly, other social costs such as the damage to disadvantaged children cannot be readily quantified, but are nevertheless important qualitative considerations.

In summary, the upfront costs of a four month lockdown can be roughly estimated to be between 15 to 20% of GDP, with scarring effects causing a permenant reduction of GDP that is far more difficult to quantify – not least because it will depend on the policy response. Given these impacts on human capital, on educational outcomes for children and on mental and physical health, it seems difficult to imagine a swift V-shaped recovery. In present value terms, a permenant drop in the order of 5% does not seem like an unreasonable working assumption.

Hatchet by Gary Paulsen

Hatchet by Gary Paulsen