Something of his Art: Walking to Lubeck with J. S. Bach by Horatio Clare

My rating: 2 of 5 stars

There is a style of book that populates the shelves of middle class homes, mostly in England. It is a gentle piece of quirky non-fiction into which you can dip on a lazy Sunday afternoon. It feels indulgently erudite, warming the insides of your university-educated ego as you delight in a particularly well-crafted metaphor, or the deployment of a somewhat archaic adjective you imagine other classes of reader would be forced to look up on their phones.

Such is the book Horatio Clare sat down to produce when writing Something of his Art: Walking to Lubeck with J.S.Bach (Field Notes). A sheaf of said field notes – most likely handwritten – lay next to a computer, perhaps held in place by a mug of good coffee, as Horatio set about recounting his ‘adventures’ while recording a BBC documentary that follows the historic walk of Johann Sebastian Bach across the Germany of 1705.

The problem is, Clare largely fails. To be fair, there are exceptionally well-written passages lost in the long and wearisome trek that is this short tract. But its central purpose – to give the reader a sense of the young J.S. Bach and his walk from Central Germany to the coastal city of Lubeck, to meet the then-famous composer Buxtehude – is lost.

We do not get Something of Bach’s Art. Instead we get a rather dry, tired account of three middle-aged men on a work assignment for the British state broadcaster. We learn much about Horatio Clare: he likes birds and wishes Europe had more of them, in that vague way of the comfortable urban naturalist shielded from the realities of the nature he adores. He dislikes right-wing populism, yet he very much likes virtue-signalling that fact. Most of all, he is rather indifferent to Bach’s music and its German cultural context, instead treating it like the work subject we know it was. He does not even bother to hide the fact that the ‘walk’ he takes in Bach’s footsteps is mostly a series of train and taxi short-cuts to the next hotel.

Perhaps not much is known of Bach or his walk to Lubeck, and so Clare had not much to tell without drifting fully into fiction-writing? Perhaps the very idea of walking in Bach’s long-erased footsteps was a silly one? Or perhaps the BBC documentary (that I did not watch) is well-edited in a way these field notes are not, and therefore tells that story much better?

In any event, we do learn something of Horatio Clare’s Art – specifically that he is prepared to put his name to a book that never ought been published; great tits, wood pigeons and all.

View all my reviews

Category: Book Reviews

My review of Daphne du Maurier’s ‘The Glass-Blowers’

The Glass-Blowers by Daphne du Maurier

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

This is not the first Daphne du Maurier novel you are likely to read. After all, she is much better known for her pacy, plot-driven psychological stories like Rebecca, The Scapegoat or Jamaica Inn.

The Glass-Blowers has little of that. In fact, at the beginning, I found it a little off-putting, because it didn’t quite rise to my expectations. The narrative device, of an opening third person narration, followed by a long first-person letter narration, and a closing third person narration, makes it hard to climb into the action in a way you might expect from a du Maurier.

But here is an excellent example of why readers should apply the 50 page rule before giving up on any book (save perhaps the most obvious trash): This book begins as an unformed lump, at first it’s hard to imagine it could be anything of value. But as du Maurier slowly and methodically breathes life into it, the story takes shape over the course of the French Revolution. It is masterfully crafted, with the contours of each character etched in crystal clarity upon an impeccably told history of the rise of the First Republic, the Reign of Terror and the ascension to power of Emperor Bonaparte.

Like the glass that acts as metaphor throughout, there is both strength and fragility in the Busson family, and especially the narrator and central character Sophie. In fact, The Glass-Blowers is nothing short of an epic; yet it is one that respects the personality of the straightforward and efficient Sophie herself, by managing to fit onto a mere 300 pages. In this, du Maurier shows respect also for the reader; something we know and appreciate from her more celebrated works.

Lovers of A Tale of Two Cities and Les Miserables take note: Dickens and Hugo do not have a duopoly on the market for great 1789 fiction.

View all my reviews

My review of Tove Jansson’s “The Summer Book”

The Summer Book by Tove Jansson

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

This is a little gem of a book – easily the best I have read so far this year.

The Summer Book by Tove Jansson is not easy to review, because the book itself refuses to adhere to conventions. In fact, it is only by having read and reflecting on this book that you are reminded how conventional much of today’s literature has become.

To say that it is a series of anecdotes about a grandmother and a granddaughter on a remote island in the Gulf of Finland is factually accurate, but does the book no justice at all. There is a story thread that runs through the book, hidden in plain sight.

To say that Jansson uses commonplace events as metaphors to illuminate deeper truths, and in so doing makes the commonplace extraordinary, is too simplistic. Jansson seems to skirt the line between metaphor and on-the-nose narration.

Her prose is sparse, and while this may reflect the work of the translator, it is somehow perfectly suited to the story and the characters.

The willful and sensitive granddaughter, Sophie, does not exactly grow up, but in the spaces between the chapter-anecdotes, which read almost nostalgically, we see the structure of the grown woman Sophie will one day become – this vision lends depth to the anecdotes and gives the reader important perspective.

And in the spaces between the grandmother’s many naps and clandestine cigarette breaks, we see that same woman: an unwritten character whose invisible womanhood binds the granddaughter and grandmother to each other, giving this short novella the breadth of a multigenerational epic.

No plot spoilers, but the final chapter made me cry. I’m not even sure if it was the subtle metaphor I imagined she was employing, or simply Jansson’s plain, beautiful writing onto which my mind projected a metaphor. And in the end, is there any difference?

Because either way, if I remain a writer and live as long as the grandmother, I would count myself lucky to ever write something as simple, as perfect and as honest as The Summer Book.

View all my reviews

My review of Len Deighton’s ‘Berlin Game’

Berlin Game by Len Deighton

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

I first arrived in Berlin in 1991, having hitchhiked through East Germany in a series of old Trabants and the odd Mercedes. It was the day the telephone company was ripping out all the old GDR public phones and replacing them with Wessie ones, and as I crossed from the lights and noise of West Berlin into East Berlin, I realised I was going to have a hard time making a phone call. In the following years, I would work (and even have one notable flirtation) with East Germans as they struggled to adjust to life in a West that had swallowed their country.

So when I picked up Len Deighton’s Berlin Game, I hoped to revisit a little bit of that intangible sense of Cold War Germany – the clash of cultures and the deeper German culture that lay underneath; the fear and hatred of the Stasi; the casual bigotry of the Wessies against the Ossies; the dull tastelessness of Communism braced against the glitzy degeneracy of Capitalism.

To his credit, Deighton tries hard to fill the book with enough details to create that mood. But that is just the problem: he tries too hard. The details are too studied to feel credible. It contrasts well with the movie Goodbye Lenin, a beautiful and compelling sketch of East Germanness that draws from the artists’ resevoir of details with the natural ease of true natives.

The other major problem is with the book’s protagonist – whose name I have (tellingly) already forgotten two weeks after reading. Who is this man? Is he the pensive, understated and soft-spoken antihero the dialogue suggests? Or is he the scary hard man, prone to outbursts of violence, whom the narrator goes to great pains to describe? After reading the book, I still cannot really say and I’m sure Deighton had no real idea.

This points to a wider weakness in Deighton’s writing. His highly stylistic descriptions are used as a sticking plaster to cover over the shallowness of his characters. I paraphrase a sample here: “She flashed him the kind of smile that said she wanted to know more about his past, but was slightly afraid to ask the question.” There are dozens of these kinds of ‘smiles’ peppered throughout the text, and I’m sure if Deighton sat down with a police sketch artist he would be unable to create a drawing of a single one of them.

Of course, the book is ultimately a spy novel, and therefore should be judged by its compelling, racy plot. But here I have to give it only middling marks. In fact, very little happens, and although the ending is somewhat surprising, it achieves this ‘twist effect’ only by sacrificing the gritty realism that kept the action credible but slow the rest of the way through.

Ultimately the most interesting thing about Berlin Game has nothing to do with spies and little to do with the Cold War. It is what the story tells us about the very English author and his own country. Deighton, son of a working class man, struggled to find a place in a Britain that had faded from power. He wrote the book at the dawn of Thatcherism, at a time when his country had been humiliated by an IMF economic programme, shocked by race relations and bruised by the paramilitary consequences of Britain’s occupation of Northern Ireland.

The result is a well-wrought tale of bureaucratic London, pervaded by wry cynicism and divisions of social class, all washed down by copious glasses of neat gin. The details are sparse, but authentic. In this, we see that Deighton is truly writing what he knew.

View all my reviews

My review of Mark Twain’s “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer”

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

There are some rules to good writing that, if followed, tend to improve the reader’s experience and make the text seem more professional. Here are four examples that are often given to would-be writers in creative writing courses: (1) avoid adverbs, (2) avoid arbitrary changes to character point-of-view, (3) show-don’t-tell, (4) keep the ‘voice’ consistent.

Of course, rules are made to be broken. Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer isn’t just good writing, it’s great writing. And yet, it breaks all of these rules, liberally and willfully. Twain’s literary dance is freestyle, the joyous rhythm of pure storytelling, which casts his narrator’s gaze across an expanse of adverbs, ‘author-splaining’ and character points-of-view as wide as the Mississippi River; all in a literary voice that changes – practically mid-sentence – from the Southern soprano of a Missouri boy to the often ironic tenor of a Yankee intellectual.

Never do you get the sense that Twain takes these literary liberties out of amateurish necessity, as cover for having been a bad student in dance class. He shows you just enough flashes of clever convention to assure you he could, if he wanted, write the whole thing in the elegant ballroom waltz of his (very English and much admired) literary predecessors: Dickens and Thackery.

But Twain’s ambition is not just to tell great stories; it is to tell great American stories. This Americanness, fresh and unburdened by convention, makes The Adventures of Tom Sawyer such an interesting read. The style is raw, because it must be raw, if it is to tell of a country still in its adolescence.

So too the eponymous central character. Tom is a flawed hero, a shabby scholar, and an undisciplined and ofttimes ungrateful nephew to his long-suffering Aunt Polly. His boyish play at piracy or robbery makes no moral distinction between good and evil, and in that, he displays not badness, but the amorality of those who have not yet tasted forbidden fruit. Equally, though, he is bursting with vital energy, courage and shows us throughout the book’s pages glimpses of the American Smooth of goodness, which his manly future self will one day master.

Most of all, Sawyer is free. Free to fight with or befriend other boys, to smoke, to break out of his house at midnight and explore distant river islands, unconventional ideas or “h’anted houses”. He is the Lord of the Dance.

In all of these ways, Tom Sawyer is not a character at all. He is the personification of this juvenile America. His Adventures, set purposefully at the dawn of the civil war, are an allegory for the rise of the United States as it shuffles forward in an awkward, uncharted yet somehow inevitable dance towards greatness.

No wonder this book has entranced generations of American readers. When they read Tom Sawyer’s Adventures, they are not just being told a story, they are being told their own nation’s biography.

Tom’s flaws are their flaws; Tom’s accomplishments are theirs too. And while this ‘Nation-State Tom’ has long since grown up, and the Republic of his manhood long since turned into an Empire frail with decay, still there remains something of that unconquerable American spirit that makes this book important.

As the rock band Rush sang of Tom Sawyer, a 105 years later:

“What you say about his company, is what you say about society.”

View all my reviews

My review of Katherine Rundell’s ‘Superinfinite: the transformations of John Donne’

Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne by Katherine Rundell

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

I first met poet John Donne there

Where in the century just gone

Every Irish not yet -man and -woman

Was made to memorise his sonnets:

On the bescribbled pages of Soundings,

That schoolbook English greatest hits

With tea stains on it.

I’ll confess he had on me the same effect

As on those his peer detractors

Who felt his metre to erratic,

His imagery too obtuse

For comfort or for ready use.

But sure, what more my story tell

Than of inner city youth?

In truth, no match for soaring

high-boned biographess

Katherine Rundell,

Whose dashing image squats a third

Of th’ rear cover sleeve in hardback.

(Her verso lips appear in colour lurid,

While Donne’s own recto, a pallid white and black)

What could I know of Souls

Like those that Donne proffered?

I who unlike her was never Fellow

Of All of them in Oxford?

With every syllable she writes she fools

Through heavy weight of accent,

Of chevron and three cinquefoils gules.

Yet ‘tis not her pride the deadly sin

That makes Kate’s lips so bright against the pages dun.

‘Tis ours – a sort of rabble pride,

We buy ‘cause we aspire

To transform two weeks in Croyde

Into something higher

Than pricey meals and a long slow, A-road, trafficked, need to stop and wee at the next station car ride.

She peddles for another sort of pride

As transformation

An inconstant poet fraud

Who sold his faith and stole his bride.

Why this odd fascination?

Because if Donne can use fine words to hide

His sins of greed, and sloth and lust,

So surely can our Kate use this pulpit of a type

To sell her stinking English upper crust

And all the sour history in it

As something more than what it is:

Sub-infinite.

View all my reviews

My review of “The Psychology of Money” by Morgan Housel

The Psychology of Money by Morgan Housel

My rating: 2 of 5 stars

Some books are so badly written, you can hear the author’s fingers banging on the keyboard, pounding out clumsy phrase after clumsy phrase so loudly it distracts from, rather than reinforces, what the author is trying to say.

The Psychology of Money is not one of those books. Actually, the writing is acceptable enough to avoid being a major distraction. Not good, mind you, but acceptable. Instead I found myself distracted by something else: the complete lack of substance. I wondered how a book so short could still feel so padded out. It was peppered with unnecessary examples and anecdotes that tangentially supported the core point of the chapter – like when he takes you back a hundred years into some semi-famous financier’s boyhood in order to illustrate the point that it is good to leave your investments to ripen, instead of harvesting them too early.

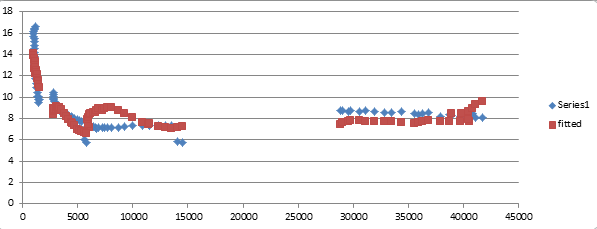

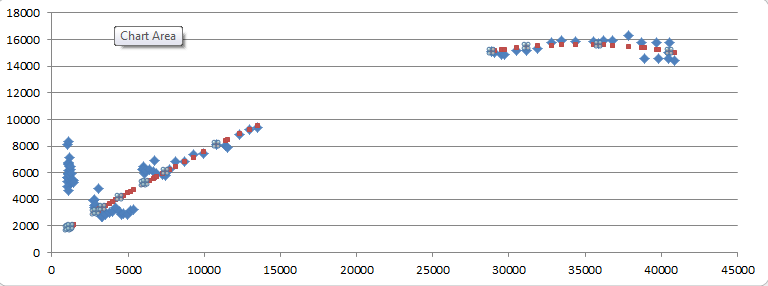

For all the padding, what was missing were any profound insights into … the psychology of money. In fact, the title ought to have been A Few Obvious, Practical Ideas for Managing your Personal Finances. But what I wanted from the book was some deeper psychology. For example, one thing that always fascinates me about money management is what I’ll call the ‘scale paradox’. Back when I was a real estate agent, I observed more than a few times how people would fight and claw to avoid paying an extra 50 cents for a dozen eggs, yet fail to put in the same effort to add an extra ten thousand dollars to the sales price of their house.

Is this because large numbers are simply inconceivable to us?

Is it because we are preprogrammed to care more about tangible, basic transactions than intangible, complex ones?

I don’t really know, because this is one of many, many interesting aspects of the psychology of money Hausel had nothing to say about.

Instead, he informed me that investors are all different, so no single investment strategy can be considered ‘best’, and that he and his wife paid off their mortgage because they like the feeling of ‘owning’ their own home.

Maybe the deepest insight from The Psychology of Money has nothing to do with the content, and more to do with the psychology of book publishing and sales. I.e. how such a shallow, pointless collection of air could sell over six million copies. Figuring that one out – at least for authors like me – would be a true insight into making money.

View all my reviews

My review of ‘The Order of Time’ by Carlo Rovelli

The Order of Time by Carlo Rovelli

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Time is relative.

You don’t need a beautifully-bound, poetry-studded hardback book to tell you that. You need only compare two very different pieces of reading material to see the principle play out – a 500 page John Grisham paperback novel, versus this above-mentioned hardback: The Order of Time, a 150 page treatise on the meaning of time and the universe, written by one of the most famous physicists alive. The Grisham you will breeze through, barely noticing as the formulaic plot unfolds effortlessly. The day and a half of reading will seem like no time at all.

The Rovelli, on the other hand, you will labour and struggle through, slowly reading and re-reading whole paragraphs, with a mounting sense of desperation as everything you thought you knew about time is methodically picked apart, and you’re not even completely sure you understand why. The weeks it takes you to finish it will feel like months.

I take pride in the fact that I did, ultimately, finish The Order of Time while on holidays on a Grecian island. It was a place where the sun bleaches out of your brain the ability to comprehend anything weightier than a young, ambulance-chasing lawyer from Mississippi cracking his first big case against an evil corporation, while saving the trailer-trashy blonde from her alcoholic, abusive husband. And yet despite the tides, tsatsiki and tarama, I managed to read and, I think, gain insights into something that is nearly as compact and dense as was the universe at the moment of the Big Bang.

I don’t claim to have fully, deeply, understood everything Rovelli sets out, so I won’t do the injustice of attempting a thorough ‘plot’ summary. In rough terms, he begins by picking apart all of our preconceived notions of how time works. He starts with the simple observation that time moves faster the closer you are to a surface of the earth, and from there gets you to a place where time, whether past, present or future, does not really exist at all, except as a cognitive dysfunction of our limited brains, linked somehow to this vague concept called ‘thermal time’ that is in turn linked to the second law of thermodynamics. Much of the details are blurry to me already, but that is probably okay because at the end, Rovelli admits that much of it is blurry even to him.

His thoughts on time take you to the very intersection of physics and philosophy, where the answers are no more solid than the baseball bat that Grisham’s hero uses on page 425 to whack the drunken husband. (Despite the six beers he’s drunk, the bat feels ‘hard’ against his skull, but Rovelli reliably informs us that both the bat and his head are in fact nothing more than a coincidence of quantum events, at some primitive stage of entropy.)

It is this blend with philosophy that also allowed me to forgive Rovelli his indulgent inclusion of poetry quotes and many tangential references to the arts. He is Italian, after all.

My only significant disagreements came later in the book. First, where Rovelli goes head-to-head with Descartes on the ‘Cogito argument’. He does not like Descartes’ “I think, therefore I am” very much, since for him there is some distinction between doubting and thinking, which Descartes does not allow in his first principle. I’m with Descartes, because I see doubt as a subset of thought.

My second bone of contention is that his whole treatise on time does not allow for any discussion of probability and determinism. This seems to me a glaring omission, because the fundamental question – it’s also a question situated at the intersection of physics and philosophy – is whether the universe is deterministic or probabilistic. This has important implications for the separation of future from present. With probabilism, the future is uncertain and must always be considered distinct from the present or past, because ex ante it is ‘unknowable’. With determinism, the only thing that makes the future uncertain is the same veil of ignorance that, in Rovelli’s reckoning, makes the past ‘blurry’ and therefore meaningfully different to the present. In other words, in a deterministic universe it is theoretically possible to know exactly what will happen, everywhere and always, from now until the end of time. ‘Future’ exists only because the supercomputers in our brains are not ‘super’ enough to do all the necessary calculations.

There is of course a third philosophical possibility, which sits between probability and determinism. It is what theologians refer to as ‘free will’ – the idea that the human soul is something special precisely because, in an otherwise deterministic universe, we humans – having been made in the image of God – are the sole entities capable of making meaningful choices. Therefore the future, and time itself, exist because humans have souls, and souls allow for choices, and not even God can predetermine what those choices will be.

If you are still reading this review, my guess is it’s felt like a relatively long read. Grisham’s protagonist would probably already have called his third witness by now.

View all my reviews

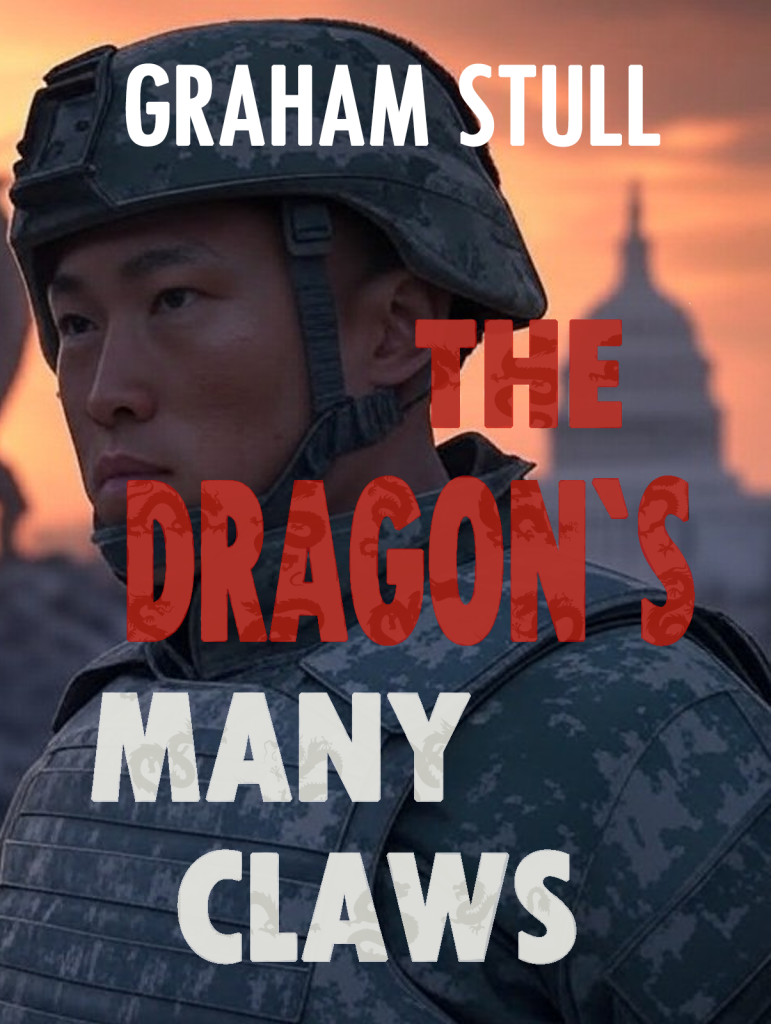

The Dragon’s Many Claws

My latest novel The Dragon’s Many Claws is now out, available on Amazon.

In some ways, I think this is my best book yet. The pacing, as an action thriller, is really good. I know this from the test readers and editors who have been through the text, but more to the point, I know it because I felt it when I was writing it.

The other thing I love about this book is that it is a war story that will appeal to people who don’t usually read war story – the same way The Hydra was a courtroom drama for people who never read courtroom dramas.

Anyway, this is where to go to buy a copy (I guarantee you won’t regret it if you do): https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0DXD56T4G

The Dragon’s Many Claws

I’m very excited to announce that my new thriller, The Dragon’s Many Claws, will be released on Amazon in paperback, ebook and audiobook on 1 February! Here’s the book cover and blurb as a teaser. Watch this space for more news!

US Army officer Stephen Chen has uncovered a plot by China to carry out a sneak attack on the United States. He’s got all the receipts and knows how to stop them before they even start. The only problem is, no one believes him.

The fight to bring the plot to light may cost Chen his relationship, his career and even his liberty. But if he is right, the fight to save America might cost the country even more.