Something of his Art: Walking to Lubeck with J. S. Bach by Horatio Clare

My rating: 2 of 5 stars

There is a style of book that populates the shelves of middle class homes, mostly in England. It is a gentle piece of quirky non-fiction into which you can dip on a lazy Sunday afternoon. It feels indulgently erudite, warming the insides of your university-educated ego as you delight in a particularly well-crafted metaphor, or the deployment of a somewhat archaic adjective you imagine other classes of reader would be forced to look up on their phones.

Such is the book Horatio Clare sat down to produce when writing Something of his Art: Walking to Lubeck with J.S.Bach (Field Notes). A sheaf of said field notes – most likely handwritten – lay next to a computer, perhaps held in place by a mug of good coffee, as Horatio set about recounting his ‘adventures’ while recording a BBC documentary that follows the historic walk of Johann Sebastian Bach across the Germany of 1705.

The problem is, Clare largely fails. To be fair, there are exceptionally well-written passages lost in the long and wearisome trek that is this short tract. But its central purpose – to give the reader a sense of the young J.S. Bach and his walk from Central Germany to the coastal city of Lubeck, to meet the then-famous composer Buxtehude – is lost.

We do not get Something of Bach’s Art. Instead we get a rather dry, tired account of three middle-aged men on a work assignment for the British state broadcaster. We learn much about Horatio Clare: he likes birds and wishes Europe had more of them, in that vague way of the comfortable urban naturalist shielded from the realities of the nature he adores. He dislikes right-wing populism, yet he very much likes virtue-signalling that fact. Most of all, he is rather indifferent to Bach’s music and its German cultural context, instead treating it like the work subject we know it was. He does not even bother to hide the fact that the ‘walk’ he takes in Bach’s footsteps is mostly a series of train and taxi short-cuts to the next hotel.

Perhaps not much is known of Bach or his walk to Lubeck, and so Clare had not much to tell without drifting fully into fiction-writing? Perhaps the very idea of walking in Bach’s long-erased footsteps was a silly one? Or perhaps the BBC documentary (that I did not watch) is well-edited in a way these field notes are not, and therefore tells that story much better?

In any event, we do learn something of Horatio Clare’s Art – specifically that he is prepared to put his name to a book that never ought been published; great tits, wood pigeons and all.

View all my reviews

Author: Graham

What more am I

What more am I

Than carbon agitation

On a rock?

A brief and pointless

Perturbation;

A speck upon a speck

Within the breath

Of entropic exhalation?

One thing more am I:

A man that hopes and yearns

That through this very poem’s craft

His tiny mind deturns

At least one electron’s path;

That a single quark, a muon

From its entangled destiny –

By the power

Of his human’s will –

Be severed.

And the universe will

Change forever.

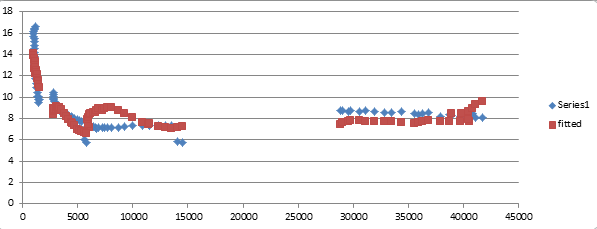

On the need to hit the Economic Gym

Christmas is coming, the Graham’s getting fat…

We have moved into the second half of November. The days are short; the temperatures have fallen, as well as a bit of snow against the windowpanes of my 18th Century country home. My fire is lit. Nothing seems more appealing now than comfort food and a blanket, curled up on the couch as I stare into the flames.

Of course, I also know what happens whenever I give in to this caveman temptation. My muscles, honed from a summer of outdoor activity, will quickly grow flabby from lack of use. After all, I am not a caveman. My cupboards are full. There is no evolutionary advantage to redirecting calories from muscle maintenance to the sustenance of biological function. In short, I must hit the gym.

Turn right in 3 metres, swivel, sit on toilet seat. You have reached your destination

What’s true for the body is also true for the mind. For example, some studies show that overreliance on GPS navigation systems can dull your ability to find your way around using your own mental maps. And we know that sudokus and crosswords stave off dementia in the elderly. The concept of honing the mind by hitting the mental gym is as intuitive as the ramifications are horrific, when we consider the growing ubiquity of AI. But that’s a subject for another blogpost.

What I want to talk about is how this principle of ‘mental gym fitness’ might apply to economic efficiency and public policy design. Policymakers know (and sometimes like to forget) that every regulation – however beneficial – has some costs attached to it. On the rare occasions when they do their job properly, they even carry out cost-benefit analysis to make sure that the benefits clearly outweigh the costs.

But what if there were another kind of cost they consistently overlook? What if regulating things that people might be able to sort out for themselves turns out to be, not only annoying and inefficient, but also harmful to our ‘economic gym fitness’?

No pain, no economic gain

Economists tend to think of ‘the rational economic actor’ as a fixed construct. In other words, it is implicitly assumed that we are endowed with a certain level of rationality or otherwise. Some people can decide what is the right level of fluoride to put in their water, but others simply cannot. Some people can make the rational decision to spend more on a car with airbags and a crash cage, but others can’t perform that analysis and, in the absence of safety regulations, will end up buying the ‘wrong’ car.

My hypothesis here is that, while individuals no doubt have innate tendencies when it comes to rational decision-making, we all get better with practice. If you live in a highly regulated society, in which the government decides what food is safe to eat, what cars are safe to drive, what words are safe to say, etc. you forget how to make these kinds of decisions for yourself. Granting freedom of speech doesn’t mean people ‘should’ say anything they like, rather that the State should never use its monopoly on violence to stop them from saying the ‘wrong’ thing. Freedom demands discretion.

Strong states make weak men make hard times

I saw the effects of this first-hand in Bulgaria, when after the collapse of communism public spaces which in Western Europe would be maintained by the community, turned into rubbish heaps and slums. Without a strong State, no one stepped up to fix or clean things. And it has taken recovering communists decades of mental gym work to rebuild that economic muscle mass.

This could be the true cost of the Nanny State: it erodes our capacity to make choices. By taking away our ability to make mistakes, the State also takes away our ability to learn from them. This could have profound effects on the overall efficiency of markets and our economy, while creating a regulatory vicious circle. For example, if consumers believe themselves safe in the knowledge that the State will regulate online shopping monopolies, they won’t feel the need to reflect on whether their one-click purchase from Amazon could have been bought in the local shop instead. Mom-and-Pop Stores die faster and the State needs to step in sooner and harder, with all that that implies: inefficiencies, risk of regulatory capture and exposure to Jeff Bezos’ fiancée’s boobs at the Presidential inauguration.

Hell hath no fury like an overregulated bureaucracy

There is perhaps also a moral dimension to this: If you depart from the premise of Judeo-Christian morality, the ability to do wrong is part-and-parcel of the ability to do right. Theology has it that we are different to the other animals God created not in any superficial anatomical way (opposable thumbs, brain to body mass…) but because we are unique among God’s creatures in having the ability to do wrong – and therefore to do right. The State, by using its monopoly on violence to block our access to the Forbidden Fruit, takes away our ability to make good choices too.

Not even the Devil would do something like that.

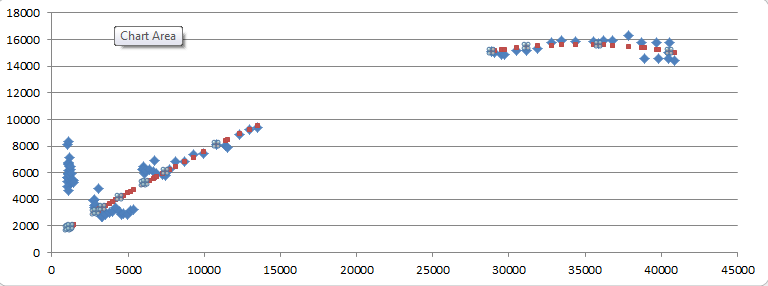

My review of Daphne du Maurier’s ‘The Glass-Blowers’

The Glass-Blowers by Daphne du Maurier

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

This is not the first Daphne du Maurier novel you are likely to read. After all, she is much better known for her pacy, plot-driven psychological stories like Rebecca, The Scapegoat or Jamaica Inn.

The Glass-Blowers has little of that. In fact, at the beginning, I found it a little off-putting, because it didn’t quite rise to my expectations. The narrative device, of an opening third person narration, followed by a long first-person letter narration, and a closing third person narration, makes it hard to climb into the action in a way you might expect from a du Maurier.

But here is an excellent example of why readers should apply the 50 page rule before giving up on any book (save perhaps the most obvious trash): This book begins as an unformed lump, at first it’s hard to imagine it could be anything of value. But as du Maurier slowly and methodically breathes life into it, the story takes shape over the course of the French Revolution. It is masterfully crafted, with the contours of each character etched in crystal clarity upon an impeccably told history of the rise of the First Republic, the Reign of Terror and the ascension to power of Emperor Bonaparte.

Like the glass that acts as metaphor throughout, there is both strength and fragility in the Busson family, and especially the narrator and central character Sophie. In fact, The Glass-Blowers is nothing short of an epic; yet it is one that respects the personality of the straightforward and efficient Sophie herself, by managing to fit onto a mere 300 pages. In this, du Maurier shows respect also for the reader; something we know and appreciate from her more celebrated works.

Lovers of A Tale of Two Cities and Les Miserables take note: Dickens and Hugo do not have a duopoly on the market for great 1789 fiction.

View all my reviews

My review of Tove Jansson’s “The Summer Book”

The Summer Book by Tove Jansson

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

This is a little gem of a book – easily the best I have read so far this year.

The Summer Book by Tove Jansson is not easy to review, because the book itself refuses to adhere to conventions. In fact, it is only by having read and reflecting on this book that you are reminded how conventional much of today’s literature has become.

To say that it is a series of anecdotes about a grandmother and a granddaughter on a remote island in the Gulf of Finland is factually accurate, but does the book no justice at all. There is a story thread that runs through the book, hidden in plain sight.

To say that Jansson uses commonplace events as metaphors to illuminate deeper truths, and in so doing makes the commonplace extraordinary, is too simplistic. Jansson seems to skirt the line between metaphor and on-the-nose narration.

Her prose is sparse, and while this may reflect the work of the translator, it is somehow perfectly suited to the story and the characters.

The willful and sensitive granddaughter, Sophie, does not exactly grow up, but in the spaces between the chapter-anecdotes, which read almost nostalgically, we see the structure of the grown woman Sophie will one day become – this vision lends depth to the anecdotes and gives the reader important perspective.

And in the spaces between the grandmother’s many naps and clandestine cigarette breaks, we see that same woman: an unwritten character whose invisible womanhood binds the granddaughter and grandmother to each other, giving this short novella the breadth of a multigenerational epic.

No plot spoilers, but the final chapter made me cry. I’m not even sure if it was the subtle metaphor I imagined she was employing, or simply Jansson’s plain, beautiful writing onto which my mind projected a metaphor. And in the end, is there any difference?

Because either way, if I remain a writer and live as long as the grandmother, I would count myself lucky to ever write something as simple, as perfect and as honest as The Summer Book.

View all my reviews

Diary of Iceland

For no reason in particular, I am taking this opportunity to republish a poem I wrote 18 years ago, after a weekend visit to Iceland.

Friday, 7:00 am – Keflavik

Rain

That speaks of cold

Boldly glistens on the tarmac

Whispers welcome strangely warm

Forms an ever-changing pattern

In the closeness of the sky.

Welcome to Iceland

Welcome to the barren straightway

Road that runs from gateway to the island’s only city.

We’ve framed it just for you –

On the left we poured an ocean’s bay

Gleaming silver in the half-suggested light of day.

On the right we laid a strip of… desolation…

At least that’s what you’d say.

You would call that desolation, that proudly can

Sustain an Iceland pony’s meagre hay.

But never mind, you’re new to us

You’ve yet to learn what lushness means to us.

For now, welcome to Iceland.

Friday, 9:51 am – Nyardvik

Three short days!

So much to see,

So much wild country

To pass in such a hurried haze

These three short days

Of childish energy!

My legs are itching for a walk

That press instead the pedals of my rented car.

Drive me into lands afar!

Where I’ll alight in sight of all I seek:

Peace and glee

And golden fleece

And above all else:

Mystery.

Friday 10:22 am – Hveragerdi

Are you so very jet-lagged?

You for whom we’ve made the welcome true

And hewn a mountain path for you to climb,

To relish in the dew, like rime,

That clings to volcanic rocks and windscreens.

Must you really rest?

Surely no night’s sleep compares

To what you now behold, Iceland’s

Greenest pastures nestled in a valley.

Come, come,

I’ll make a bakery appear, just here on the right,

Neat and clean, with cafe seating and a toilet.

Have a doughnut and a Danish and a coffee strong as spit,

Maybe you should read a bit

Your book about the Iceland farmer who never quit.

Rise up now, like Bjartur,

You have not yet seen my best.

I promise much will happen ‘ere you rest.

Friday 11:30 am – Geysir

That is not the Earth;

Those proud bare scrags

Jagged hilltops breaking where the valleys start.

That is not the Earth;

The road that winds between the Autumn grasses,

Their pastures torn apart.

Nor is the Earth

That ocean far behind me,

Whose salty waves and brine,

Like wrapping paper coat the world

In all things maritime.

THIS is the Earth:

A bubbling cauldron from the depths of Hell,

That tells of molten fire beating like a heart.

See it spew a spray of boiling mist! (We gasp)

The slightest spasm of its burning core, nothing more.

It cares not if the tourists’ cameras click with curiosity

Or if they step withing the water’s reach

And screech in burning agony.

Indifferent too, the bubbling pool of blue-green jewel,

Odour warm with sulphur,

That asks in gurgles random,

How deep am I?

I cannot fathom.

But one thing now I know is clear,

Mother Nature is no fair flower of the spring.

She is a core of liquid rock,

And where her outstretched finger stirs the top, the air

It’s there you’ll find a place called ‘Geysir’.

Friday 12:40 pm – Gullfloss

Superstition’s what they call it,

Viking tales and sagas old

That tell of faeries, elves and trolls.

Now you see the mighty Gullfloss Falls

Where crystal water pounds the rock

To sheets of rising mist and mystery.

This is Iceland’s history.

And look! You see that profile

Carved into the cliffside?

See the gaping mouth and eyeless sockets

Seething wild with power

That pitiless a Viking child devour?

Now turn your glance

To where a vapour lifts its spray

See that in the shifting mist exists

A host of dancing creatures, Elves.

That freed, at last exult themselves

In one fast flight to heaven.

They call it Superstition

These so-called men of science

And come with words in Latin

To rob us of our Nordic right;

They who’ve not spent a single moonlit night

In wary sight of dancing faeries and the Gullfloss Troll

Have stole our legend, thieved our vision

And given us instead their Superstition.

Friday 4:00 pm – Route T3

Desolation

The desert speaks in tones of eerie silence.

No trolls live here, I hope

And hope my rented Opel holds together

Along this fading track –

I could turn back –

But oh! what a view.

The untamed mountains, wild beyond nature,

Upon which is perched a Glacier

See, it bursts into the valley

Then issues forth a lake of nearly frozen pureness.

Stop. This hut atop the hill

Equipped with bunks and filled with Glacial views

Built to use in case of jet-lag.

Here I’ll unfurl my sleeping bag

For today I’ll go no further.

Friday 6:00 pm – Hvitarvatn

They’re coming

At the window panes, the party

Their hearty Nordic frames

They ride on auburn ponies

Iceland’s proudest sons

Gather sheep and sleep in huts like this one.

Did I day ‘sleep’?

Here’s Ole and Ardur and a case of beer and liquor.

Come join us for a drink or eight

There’ll be no sleep at any rate

Until the perfect moon has cast its parting glimmer

On the ice of Langjokull.

We will sing tonight

And dance and eat boiled sheepshead

And will not sleep, but laugh and joke and brag

And you’ll forget there ever was a thing called jet-lag.

Saturday 10:30 am – Route T37

My stomach groans in protest

My temples pound in protest

My rented Opel creaks in protest

As the road grows worse and worse

The price I pay seems high today

But the memory of revelry

Will far outlast these morning-after ailments.

How long ’til Hveravellir is reached?

This eternal path of potholes be damned!

I need some bread, some water and a break.

There. Now I see it, rising geysir steam

A shack or two, the promise of a road improved.

And food.

Saturday 12:00 noon – Hveravellir

Can even dreams perceive this kind of peace?

To lie half-naked in a clear blue pool, a hot spring bath

While silent snowflakes melt against your steaming face

And into snow-capped highlands runs the wandering path.

Iceland’s greatest treasure is its peace, it seems

In such a place we live beyond our dreams.

Saturday 3:00 pm – Blonduos

Receding mountains

Speeding roads

And all at once

The coast explodes,

Fjords of water, fingers now unwind,

That leave the lava desert far behind.

Little village clinging to a shore

A score of houses on an ocean striking

A fishing boat and a pub names Viking

And a guesthouse with a pillow soft as rest,

And as comfortable

As only deep and dreamless sleep can be.

Sunday 10:30 am – Route 1

Soak it in!

The last time I’ll enjoy this weekend spectacle.

The she-troll’s gorge

Volcanoes forged and fading

Their blackened memory pervading

Mocks the grass and flowered greenery

Scarred with rocks and smitten scenery.

Drink it in!

Crystal pure, its gushing source

Where all the water in the world begins

Trickles, falls in fickle sprawls

Ever downward with enduring force.

Now pause to wet my wind-cracked lips

In ample sips

A momentary detour from its everlasting course.

Breathe it in!

What air was always meant to be

Where no debris, nor dust, nor industry

Has sullied these chill gusts

That thrust in heavy gulps upon my lungs

The welcome must of inhalation.

I almost fear to leave you, Iceland,

Though the road cuts south

And straight away along the ocean’s mouth

Into the bay they call ‘Reykyavik’.

Let me stop at one last scenic view

To soak and drink and breathe and plead

That you embue in me a tenth, a hundreth even

Of this perfect paradise.

Monday 3:00 pm – Kalfatjorn

Come out of that tent, you lazy tramp!

Greet your spectral guests

That dance in moonlit circles

Round your makeshift camp.

They are faeries, magic imps

Summoned from the sprigs of heather

Called together from the regions nether

To haunt you in that tent you tethered.

Was I their summoner?

No, not I (though such powers I possess)

Rather, it was a lesser sorceress.

The Celtic witch called Columkill

Who through countless spells’ enchantment

Has earned dominion o’er this hill

And o’er your meagre night’s encampment.

She ordered up this ghostly host

Perhaps because you’re Irish too

To bid farewell to one who came

And knew a place where spirits dwell

In every dell, on every mountain face

Atop the Glacier and along the strand

That forms the paegan soul of Iceland.

We will spend this last night with you

In frenzied revelry aglow

Atop the witch’s hill that frowns

Upon the little coastal towns below.

And when the dawn emerges

Propelling from the Eastern sea the newborn sun

We’ll be dispelled, our magic done.

The day will carry you away from our strange company

And into the sky

And so I whisper now

With half-heard mystery, like a sudden whisp of cloud

My last goodbye.

Back to school! My 22nd Letter to you

Dear Daniel,

I hope you had a wonderful summer and are ready to go back to school.

The back to school season is an exciting time. A chance to meet up with old friends and a chance to meet new ones. I always found that although you are back in the same environment, somehow everything is changed. Because of course, you have changed – with new experiences and ideas learned over the summer break.

Our summer was wonderful – lots of swimming in the sea and lakes, horseriding for your sister, good food and a chance to catch up on books (I post reviews of all the books I read on this blog, so you can always see my reading list).

Now it’s time to get back to work.

I am thinking of you and missing you, as always.

Love,

Dad

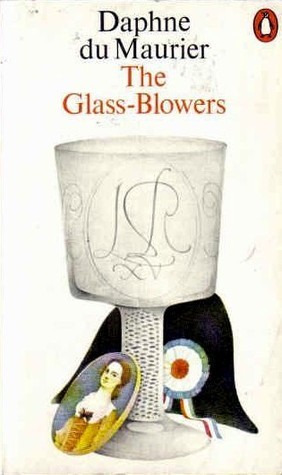

My review of Len Deighton’s ‘Berlin Game’

Berlin Game by Len Deighton

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

I first arrived in Berlin in 1991, having hitchhiked through East Germany in a series of old Trabants and the odd Mercedes. It was the day the telephone company was ripping out all the old GDR public phones and replacing them with Wessie ones, and as I crossed from the lights and noise of West Berlin into East Berlin, I realised I was going to have a hard time making a phone call. In the following years, I would work (and even have one notable flirtation) with East Germans as they struggled to adjust to life in a West that had swallowed their country.

So when I picked up Len Deighton’s Berlin Game, I hoped to revisit a little bit of that intangible sense of Cold War Germany – the clash of cultures and the deeper German culture that lay underneath; the fear and hatred of the Stasi; the casual bigotry of the Wessies against the Ossies; the dull tastelessness of Communism braced against the glitzy degeneracy of Capitalism.

To his credit, Deighton tries hard to fill the book with enough details to create that mood. But that is just the problem: he tries too hard. The details are too studied to feel credible. It contrasts well with the movie Goodbye Lenin, a beautiful and compelling sketch of East Germanness that draws from the artists’ resevoir of details with the natural ease of true natives.

The other major problem is with the book’s protagonist – whose name I have (tellingly) already forgotten two weeks after reading. Who is this man? Is he the pensive, understated and soft-spoken antihero the dialogue suggests? Or is he the scary hard man, prone to outbursts of violence, whom the narrator goes to great pains to describe? After reading the book, I still cannot really say and I’m sure Deighton had no real idea.

This points to a wider weakness in Deighton’s writing. His highly stylistic descriptions are used as a sticking plaster to cover over the shallowness of his characters. I paraphrase a sample here: “She flashed him the kind of smile that said she wanted to know more about his past, but was slightly afraid to ask the question.” There are dozens of these kinds of ‘smiles’ peppered throughout the text, and I’m sure if Deighton sat down with a police sketch artist he would be unable to create a drawing of a single one of them.

Of course, the book is ultimately a spy novel, and therefore should be judged by its compelling, racy plot. But here I have to give it only middling marks. In fact, very little happens, and although the ending is somewhat surprising, it achieves this ‘twist effect’ only by sacrificing the gritty realism that kept the action credible but slow the rest of the way through.

Ultimately the most interesting thing about Berlin Game has nothing to do with spies and little to do with the Cold War. It is what the story tells us about the very English author and his own country. Deighton, son of a working class man, struggled to find a place in a Britain that had faded from power. He wrote the book at the dawn of Thatcherism, at a time when his country had been humiliated by an IMF economic programme, shocked by race relations and bruised by the paramilitary consequences of Britain’s occupation of Northern Ireland.

The result is a well-wrought tale of bureaucratic London, pervaded by wry cynicism and divisions of social class, all washed down by copious glasses of neat gin. The details are sparse, but authentic. In this, we see that Deighton is truly writing what he knew.

View all my reviews

My review of Mark Twain’s “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer”

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

There are some rules to good writing that, if followed, tend to improve the reader’s experience and make the text seem more professional. Here are four examples that are often given to would-be writers in creative writing courses: (1) avoid adverbs, (2) avoid arbitrary changes to character point-of-view, (3) show-don’t-tell, (4) keep the ‘voice’ consistent.

Of course, rules are made to be broken. Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer isn’t just good writing, it’s great writing. And yet, it breaks all of these rules, liberally and willfully. Twain’s literary dance is freestyle, the joyous rhythm of pure storytelling, which casts his narrator’s gaze across an expanse of adverbs, ‘author-splaining’ and character points-of-view as wide as the Mississippi River; all in a literary voice that changes – practically mid-sentence – from the Southern soprano of a Missouri boy to the often ironic tenor of a Yankee intellectual.

Never do you get the sense that Twain takes these literary liberties out of amateurish necessity, as cover for having been a bad student in dance class. He shows you just enough flashes of clever convention to assure you he could, if he wanted, write the whole thing in the elegant ballroom waltz of his (very English and much admired) literary predecessors: Dickens and Thackery.

But Twain’s ambition is not just to tell great stories; it is to tell great American stories. This Americanness, fresh and unburdened by convention, makes The Adventures of Tom Sawyer such an interesting read. The style is raw, because it must be raw, if it is to tell of a country still in its adolescence.

So too the eponymous central character. Tom is a flawed hero, a shabby scholar, and an undisciplined and ofttimes ungrateful nephew to his long-suffering Aunt Polly. His boyish play at piracy or robbery makes no moral distinction between good and evil, and in that, he displays not badness, but the amorality of those who have not yet tasted forbidden fruit. Equally, though, he is bursting with vital energy, courage and shows us throughout the book’s pages glimpses of the American Smooth of goodness, which his manly future self will one day master.

Most of all, Sawyer is free. Free to fight with or befriend other boys, to smoke, to break out of his house at midnight and explore distant river islands, unconventional ideas or “h’anted houses”. He is the Lord of the Dance.

In all of these ways, Tom Sawyer is not a character at all. He is the personification of this juvenile America. His Adventures, set purposefully at the dawn of the civil war, are an allegory for the rise of the United States as it shuffles forward in an awkward, uncharted yet somehow inevitable dance towards greatness.

No wonder this book has entranced generations of American readers. When they read Tom Sawyer’s Adventures, they are not just being told a story, they are being told their own nation’s biography.

Tom’s flaws are their flaws; Tom’s accomplishments are theirs too. And while this ‘Nation-State Tom’ has long since grown up, and the Republic of his manhood long since turned into an Empire frail with decay, still there remains something of that unconquerable American spirit that makes this book important.

As the rock band Rush sang of Tom Sawyer, a 105 years later:

“What you say about his company, is what you say about society.”

View all my reviews

The Age of Post-outrage

Upon hearing the news that the French journalist Natacha Rey was cleared by a French court of defamation in her case against Brigitte Macron, I was prompted to consider the consequences. To be clear, Rey’s claims about France’s first lady are spectacular and scandalous: that ‘she’ is in fact a man, most likely ‘her’ own brother Jean-Michel Trogneux, and therefore that Emmanuel Macron has been duping the French public and the world for nigh on a lifetime.

To be even more clear, I am agnostic on the substance of these charges. If true, I’m not even sure I attach all that much significance to it – I have always held that public figures should be judged for their public actions, not their private ones.

But none of that is the point, because my views are not what matters. What matters is that, under normal circumstances, this should be the Scandal of the Century. After all, it appears that the French voters were lied to. It also raises important questions about issues of state – who has what kompromat behind this salacious truth? Every newspaper, every television, every corner of the Assemblée Nationale should be abuzz with the controversy. Rightly or wrongly, pressure should be mounting on Brigitte Macron to take whatever simple and obvious steps could be taken to dispel this ‘fake news’. (Of course, if that were possible, one must assume her legal team would already have presented that evidence to the Court, and the defamation case would have been won against Rey).

So the real question is not whether Brigitte Macron is the same person as Jean-Michel Trogneux. It is why, in the face of relatively strong evidence that this might well be the case, widespread public awareness is not triggering any political immune response. We appear to have moved beyond the point where the system is capable of focusing enough outrage over issues that in the past, would have constituted major scandals.

Brigitte-gate is not even the most egregious example of this. Take the issue of lab leak. Whatever one still thinks about the Covid ‘vaxxines’, there is now virtually no serious disagreement – neither in scientific circles nor in the public at large – over how this virus came to be: Taxpayer-funded research networks, most likely linked to bioweapons programmes, gave money to a lab in Wuhan China to carry out gain-of-function research on a bat coronavirus. Some variant escaped and became SARS-2, spread across the planet and killed millions of people.

At this stage everyone knows this is what happened. But once again, the outrage is missing. Not only have the authors of this human catastrophe not been held to account, they are in fact still receiving taxpayer funding to carry out more of the same kind of deadly research. When I wrote a fictional book about a 2020 virus, back in 2015, this is the thing I got most wrong. In The Hydra, the outrage is a key theme – it topples governments, it motivates vast public interest, it moves the plot along, in fact. But I wrote that book at a time and in a world where tectonic events caused political earthquakes.

Nor is Covid even the most egregious example. We now live in a world where, not only do we passively watch a genocide unfold using weapons we have paid for, but when the author of that genocide nominates his principle weapons supplier and financial backer for a Nobel Peace Prize, barely anyone blinks. We sit dumbly and shrug as that same weapons supplier flatly tells us that although Ghislaine Maxwell was guilty of five counts of sex trafficking, she trafficked those children to no one at all. Kash Patel’s team didn’t even bother to edit the time stamps for the missing minute in the surveillance video tape of when Jeffrey Epstein was murdered (something I could have done with Adobe After Effects and a few days of careful work).

This kind of political numbness is not new. We saw a similar relationship between demos and veritas among the citizenry of the Soviet Union. A sort of cynical acceptance of the complete disconnect between official narratives and the quietly understood reality of everyday people, best encapsulated in the quip: They pretend to pay us, we pretend to work.

It would be foolish to believe this is harmless. If nothing else, it speaks of a dangerous apathy among the masses that threatens the pluralist roots of our society, and breeds a culture of impunity among those in power. At its worst, it leaves us defenseless against corrosive influences. After all, biological creatures have immune responses for a reason – to warn us of when destructive pathogens have penetrated our systems, and then to mount a defense.

If we’re not careful, we might end up in a situation where one of the world’s nuclear powers is ruled by a man who, at age 39, sexually preyed on a 15 year old boy, while pretending to be a woman.