The pearl-clutching and hand-wringing over Trump’s tariff chaos is a thing to behold. The shock, particularly among Europeans, is almost as funny as it is silly: after all, Trump told us he was going to bring in tariffs during his election campaign. He led in the polls, duly won the election and is now following through on his campaign promises. It says much about how the transatlantic elites view political promises themselves, that they appear genuinely surprised to see Trump doing exactly what he promised his voters he would do.

What is even more hilarious are the post hoc condemnations of this transparent effort to redefine the architecture of 20th Century global trade. Suddenly, long-time critics of globalisation are rushing to its defence, using arguments so textbook that they could have been cut and pasted from a 1980s economics textbook: Prices will go up, growth will stall, the uncertainty will kill business, third worlders will suffer, retaliatory tariffs will hit America hard…

Economics 101: trade is good for everyone, dummy

To get behind this debate, it’s useful to go back to the basics of economics. Every student will remember the name David Ricardo, and the conclusions of his basic trade model that show that when two nations trade together, they both get better off. The intuition behind the Ricardian model is simple: the United States specialises in, say, computer engineering and trades the IT to Vietnam, which specialises in tailoring shirts. Because the US has a comparative advantage in computers and the Vietnamese a comparative advantage in making shirts, everyone is strictly better off from the trade.

“Let them eat cake from the Googleplex free buffet”

The problem is what happens to the American shirt makers who are put out of work. In Ricardo’s defence, this was less of a problem in the year 1800, because at the time, Britain’s industries were booming and the factories of Manchester, Sheffield and Stoke had a near insatiable demand for unskilled labour. Even so, free trade worked to depress their wages too, but this effect was invisible in the general rising tide of industrialisation. It would take decades before the horrific inequality and exploitation of unfettered capitalism gave rise to a countermovement, in the person of a handsomely bearded German-Jew named Karl.

In 21st Century America, the story is not quite the same. Voters from flyover states see with their own eyes the factories close down and the poverty set in. Barack Obama’s solution for the out-of-work shirt makers was that they must learn to code. I encourage you to watch the video clip, because the political moment proved to be weighty. In 2013 it took Obama and his out-of-touch DC advisors completely by surprise that this message would backfire so badly. They never imagined that it would help elect Donald Trump a few years later.

Looking at it through the lens of 2025, ‘Learn to Code’ seems absurd. A 50 year old forklift driver from small town North Carolina will not be able to start programming apps in California, when the crates of shirts he loads into trucks are outsourced to Vietnam. For despite what Obama claimed, ‘nearly anyone’ can not learn to code.

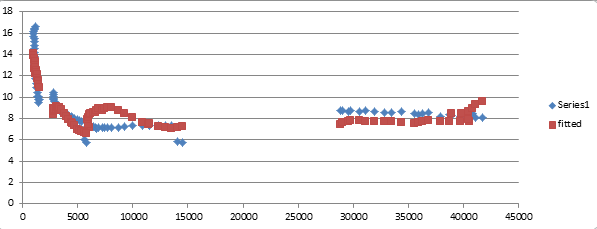

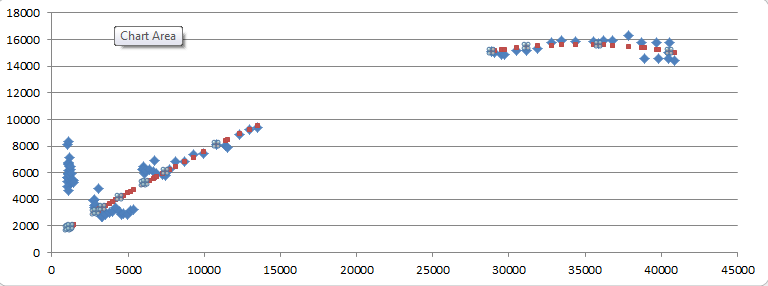

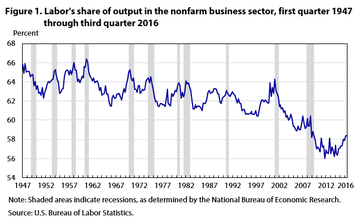

This is the essential point from the tariffs debate: because inequality is as high as it is, it is not only possible that market contraction and negative GDP growth be consistent with an improvement in the quality of life of the median American, it is almost axiomatic that this will be true. Because the real issue at stake is that as America shifts production into ever higher-valued added output, the labour share of income has been continuously shrinking. Don’t take my word for it, just look at the chart from the Bureau of Labor Statistics below.

The steady erosion in how much of the country’s income went to labour, as opposed to capital, began to markedly accelerate in the 2000s as the bipartisan trade liberalisation agenda was rolled out and China emerged as a supplier-superpower to replace US manufacturing. Yes, cheap imports kept prices low. Yes, rock-bottom interest rates meant impoverished workers could borrow cheaply. But with widening income inequality, they were always getting worse off, even as the country got richer in exactly the way Ricardo would have predicted.

Trump’s tariffs are his promise to the ‘Left-Behinds’ to turn this process on its head. And let’s be clear: there is every reason in economics to believe that tariffs – however haphazardly imposed – will succeed in increasing the labour share of income by reshoring labour intensive manufacturing. Some cost will be born by the consumer, but because prices are elastic on many consumer goods with global supply chains, most of the cost will be born out of the rents that accrue to capital. Money will flow inland from Connecticut to Ohio; and from California to Wyoming.

The three-headed hydra choking the American working class

Of course, trade is not the only factor driving a deterioration in labour’s share of income. It’s a hydra with two other heads: mass-migration and technology. Mass-migration is, in fact, perfectly analogous to production outsourcing through trade liberalisation, except that instead of having your blue collar job go to a third worlder overseas, the third worlder crosses the sea to take your blue collar job. He might take your house too.

I know, I know. Lot’s of reputable economists will vehemently argue against this, claiming that migrant labour is wage-augmenting etc. But it’s notable that none of those economists actually works in a factory. They have never been told that if they don’t want to work late shifts on a Saturday for no extra pay, there are twenty Mexicans who will be happy to take their place. Trump’s supporters, on the other hand, have been told this, which is why they gave their Orange Man a clear mandate to do something about it.

Then there’s technology. Here the economists are a little more attentive to the risks of labour displacement, perhaps because AI software does a better job at forecasting GDP than robots do at stitching together Ralph Lauren shirts. The principle is the same as with trade: every labour-saving innovation shifts more income to capital and away from labour.

And while Secretaries Besset and Noem have shown how they can take care of trade and migration pretty well, it’s not clear to me what, if anything, Trump is prepared to do about the dangers tech poses to the American working class. The President of Mars appears to have a veto over the President of the United States of America, and His Autistic-ness is all for loosening – not tightening – the noose on the Big Tech monopolies that are currently stealing our jobs and our souls.

Cuz man these god damn food stamps don’t buy … self respect

What of the opposition?

Back when Democrats still pretended to care about this problem, their solution was generally some form of fiscal transfer: essentially to tax some of the output gains from capital and give it to labour as welfare benefits. This would compensate them for their share loss in the open borders, trade liberalised, technology-pumped economy. Politically, it’s not hard to see the appeal – you create a system where voters are dependent on hand-outs from government to compensate them for their loss of income created by government policies.

But there are many problems. First, capitalists are insanely good at sneaking past that fourth space on the Monopoly board. This means that in practice, the welfare transfers will have a hard time keeping up with the loss in income share. More importantly, people do not just work in order to have food on the table. They work in order to be part of society, to have a feeling of accomplishment and achievement, something fiscal transfers can never provide. People don’t want hand-outs, they want economic sovereignty.

And to get it, they are prepared to elect an orange-faced egomaniac; they are prepared to see their country’s place in the world economic order decline; they are prepared to endure higher prices; all in order to restore the pride of knowing they are a meaningful part of the economy. They might buy fewer things, but the things they buy will be made by someone whose values they share.

Before you judge them as being short-sighted, do a few shifts in an American factory. If you can find one that is still open, that is.