Empires do not fade in a day. If you asked a British citizen when exactly their empire collapsed, they might point to the 1947 announcement of withdrawal from India, the British Empire’s crown jewel, as the landmark moment. But in reality, this merely formalised a shift that had been underway since the 1919 Government of India Act, the granting of home rule to the Irish Free State a few years later, and a whole host of other concessions the island rulers were forced into making as their economic and military power declined. By the end of World War II, the Empire had ceased to exist in all but its name, and in the collective consciousness of those old colonels living in a run-down seaside hotels, telling tourists about the time they hunted the Bengali tiger.

A hundred years later, the same might be said of that Empire known by euphemisms like – ‘the Western World’, the ‘liberal world order’, or my personal favourite: ‘the International Community’ – but is, in reality, better called the American Empire.

Not without some irony, Lingchi, the Chinese death by a thousand cuts, best describes what has been happening to this Empire. Cultural narratives like critical race theory and transactivism are tearing apart the Empire’s collective sense of self. As counterculture movements they are divisive by design. On the economic front, the steady offshoring of manufacturing capacity and the overeducation of a whole generation of unproductive soy-infused urbanites has left the Empire economically reliant on its favourable global terms of trade in order to maintain high standards of living among its ruling classes in the Coastal USA and in Europe. The legacy financial architecture, in the form of the petrodollar and the Bretton Woods institutions, grows shakier with every passing bank bailout. The ill-advised choice to politicise the SWIFT global payment system further erodes those financial foundations. At the same time, the self-hating ideology of climate activisim not only undermines the Empire’s own energy supply, but also heralds a steady attack on its productive capacity. Europe is about to ban combustion engine cars, a technology in which it maintains a historic advantage, in favour of battery-powered ones where it is forced to compete with China on more level terms, and where it is completely dependent on imported raw materials.

What, then, remains of the Empire and its ability to enforce its system of goverance on its global dependents? There is still some measure of political and cultural good will. While not entirely guiltless, this Empire has been more benevolent that many that have come before it, and American cultural exports like McDonald’s and Hollywood have made the Empire’s mass culture seem both accessible and aspirational. But I would argue that this good will has largely dissipated. Since Covid at the latest, the Empire is no longer a good ambassador of its own liberal values, if indeed it ever was. Hollywood has eaten itself, and Wokeism is a singularly unattractive cultural export for those in the far reaches of the Empire who feel neither guilt for American slavery, nor a desire to blur the gender divide between men and women.

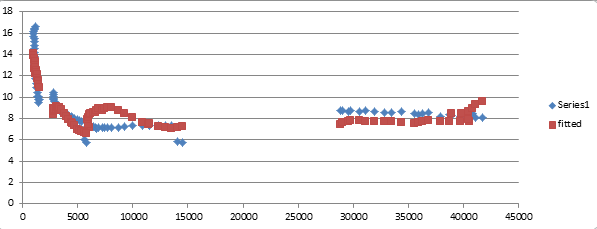

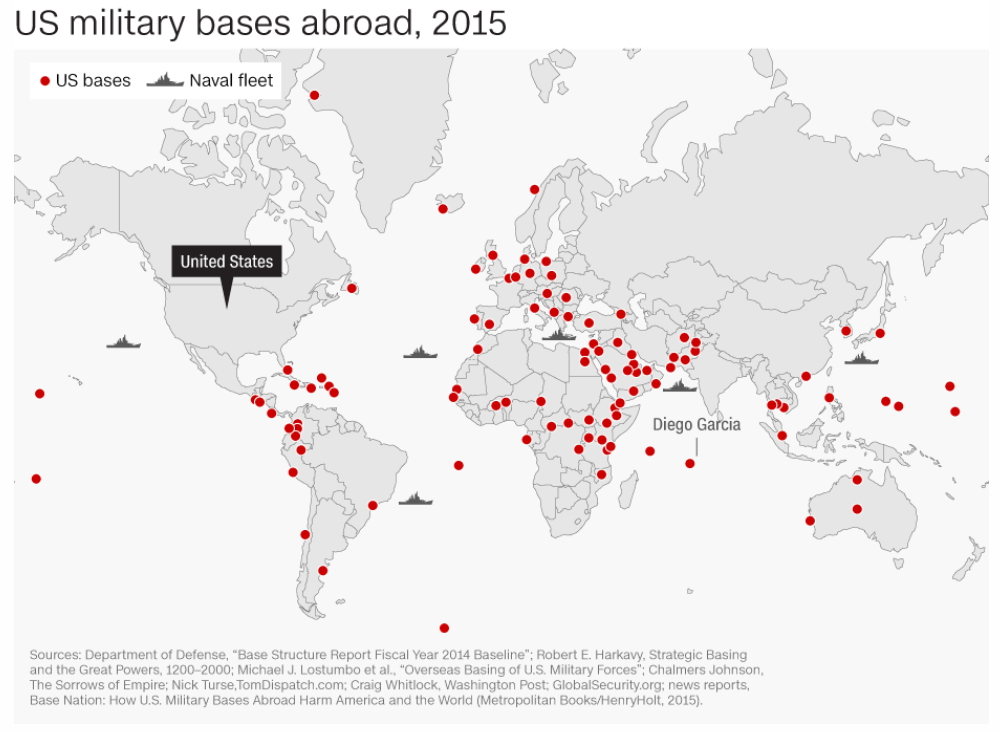

What the American Empire still has, of course, is the world’s mightiest military – effective control of international shipping lanes, satellite communication and a network of bases that neatly spans the globe. But the world is big, and as the map shows, there’s an important gap in the Empire’s coverage, right where it matters most. With the exception of volatile Pakistan, the withdrawal from Afghanistan has left the Empire with virtually no foothold on the biggest and most valuable continent: Asia.

In fact, on closer inspection the Empire’s military grip is tenuous. Sloth in the military industrial complex and avarice among the Empire’s European vassal states have hollowed out its real fighting capacity. For the most part, the Empire rests on its historical reputation and on the fact that its adversaries lack coordination. The fear of American power – rather than the reality of its execution – has, up until now, been enough to deter any meaningful resistance.

In this context, the breakthrough success of the Indian film RRR gains new significance. A smash commercial hit for Netflix, the three hour Tollywood blockbuster tale of friendship and revolution in 1920s occupied India enchanted audiences well outside of Hindustan. That the navel-gazing, ultra-woke Hollywood Insiders chose to shower Oscar recognition on it is less important than the fact that it was watched – and loved – by the Empire’s ordinary subjects, just as much as by the barbarians outside its borders.

Because RRR is not an Indian imitation of a Hollywood film. It is unwaveringly, unflinchingly and unashamedly not Western. With its cinematography, its over-the-top choreography and its Hindi-language in-jokes, this film makes no attempt to appeal to Western audiences. Its global success is the proof that today, that is not even a requirement.

Most shocking is the depiction of the Westerners. The British colonial occupiers in RRR are not just ‘bad guys’. They are depraved, morally bankrupt and palpably evil. The only redeeming Western character is Jenny (Olivia Morris), the white woman who falls in love with the dominant Indian protagonist, and who finishes as a happy bride, dancing in a sari and singing in Hindi, unphased by the brutal annihilation of her wicked family and loss of her Western way of life. The message is clear: we’ll take their women too.

Yet that is not the worst. Nor is it even exceptional – after all, unflattering depictions of the West have been common in Western media for decades. The truly shocking thing about the British villians in RRR is that they are weak. Physically, morally and intellectually weak. They recoil as cowards against the righteous outrage of the Hindi protagonists. They cannot shoot for beans and they lack the physical strength of Indian men.

Whether this is an historically accurate and fair depiction of the British Army during the Raj is entirely beside the point. What matters is that in a global blockbuster that out-eyeballed all but a handful of Western films last year, the Indian director feels empowered enough to depict the West as hopelessly weak. And barely anyone bats an eyelid. India’s foreign minister even used the representation as a barb, in conversation with the American Empire’s foremost disgraced lapdog, Tony Blair.

A few months later, the world witnessed the spectacle of Presidents Xi and Putin embracing each other during a state visit to Moscow with a display of friendship and complicity that left little doubt about their intentions with respect to the American Empire. Neutral spectators from Latin America to Africa, to the Indopacific are watching. And now, they are no longer sure the West can contain this new Asian Axis. With emergent Hindi nationalism as a tailwind, and given the subcontinent’s historic links to the USSR, there is no guarantee that India will heed the American Empire’s warnings not to slide too far into a Putin-Xi rebel alliance.

After all, as RRR has shown, the world may have less to fear from weak, evil Westerners than the US State Department would like them to believe.