‘You can never been overdressed or overeducated’

It is a widely held tenet of modern liberal thinking that there is a strictly positive relationship between the amount of education in a society, and the health of its politics and economy. When I say ‘widely held’, I mean to include my former self in that particular bubble of groupthink. I have a couple of masters degrees and a BA – achievements of which I have always been proud – and so perhaps it was out of pure ego that I always imagined that with more education, would come better public accountability for our representative democracies, greater labour productivity and a more effiicent use of public resources for the benefit of all. I must have thought: if more people were like me, how much better a world we would have!

Houston, we have a problem

Then along came SARS-2, wafting out of a wet market and certainly not the virology lab across the road (pay no attention to that bat lady behind the curtain!). In a flash of media madness, decades of established wisdom on public health was thrown out the window – on the efficacy of community masking to prevent respiratory virus transmission, on pandemic planning, and on the correct way to approve and make available novel pharmaceutical products. Basic facts that were immediately and publicly available were ignored and labelled misinformation or conspiracy-think – such as the fact that SARS-2 had an infection fatality rate of 0.3% (lower in age-adjusted terms), and was therefore not that deadly. Bizarre doctrines like Zero Covid emerged in the teeth of common sense and all available evidence. ‘Long Covid’ became an article of faith, a gospel reading in the Church of ‘The Science’.

Was it simply panic? Perhaps in the early weeks. But as the hysteria wore on and the masks literally muffled any dissenting voices, I noticed a strange pattern among the Covid Zealots I knew – they were, with few exceptions, those who had the most higher education. Whereas the received wisdom on the benefits of higher education suggested they should be most able to critically dissect what was happening and make sense of it, they in fact proved to be least able to do so.

Saving grandma and a nasty commute, both at the same time

Many critical thinkers I know attributed this to simple self-interest. The laptop class was, after all, able to comfortably telework throughout the lockdowns. Many even relished the reprieve from painful commutes into crowded office buildings. They were certainly not the waiters, shopkeepers or small business owners most immediately impacted by closures. To borrow a phrase – it’s hard to make a soy-infused Guardianista understand something, when continued enjoyment of they/their home office depends on them/they/they’re/their not understanding it.

But this doesn’t explain the more extreme manifestations of Covid Zealotry, such as the willingness to subject oneself and one’s own children to an experimental treatment with no obvious benefits and unknown risks. Data shows that higher education levels are correlated with higher ‘vaccine’ uptake. Likewise: mask wearing was nowhere as ubiquitous as in the ivy-clad enclaves of New England’s educational elites. There can be no doubt – the well-educated actually believed this worm-infested horse crap.

Some readers might shrug this off as an obvious conclusion. The fact that college-smarties lack common sense is nothing new to the working classes who fix their leaky roofs, service their cars and install their ergonomic workspaces.

I think I thought I saw you try…to think

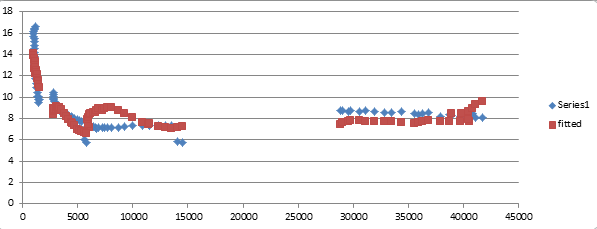

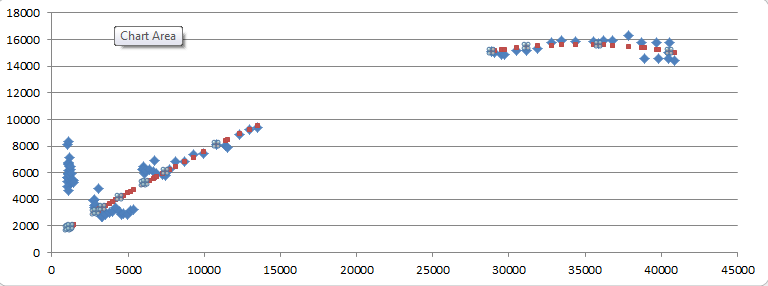

But perhaps there is a deeper point to be made about the nature of cognition and how it has changed in the age of mass higher education. In general, when we learn something new, we go through an inductive process of reasoning. A leads to B leads to C … which leads to a result. For example, if I want to learn how to fix the clogged drain in my bathroom sink, I need to understand how the u-bend works, what seals are there to stop leaks. Where the water will flow when I open the plumbing, etc. then I can figure out what to do first. I create a mindmap of understanding.

Now imagine I attempt to ‘learn’ something that is complex beyond my ability to construct the relevant mindmap. Imagine, for example, that I simply cannot follow all the threads of thought that allow for a complete understanding of the quantitative theory of money. Of imagine I am unable to prove from first principles the power rule in differential calculus. What becomes of me?

In a world where these respective tenets of economics and mathematics are kept as the preserve of a true intellectual elite, the answer would be: I am told by my professor that I don’t grasp the thing, I am handed a failing note and I go back to unclogging u-bends under bathroom sinks.

The democatisation of education ensures we get the graduates we deserve

But in the age of mass higher education, this is very much not what happens. The greater the number of intellectually average people admitted into the halls of knowledge, the more fails a professor would have to hand out, and that isn’t good for business. And so instead, a short cut solution is provided. I might not ‘get’ monetary theory, but I can accept as dogma that M x V = P x T. I might not ‘get’ calculus, but I can accept as dogma that f'(x) = r*x^(r-1) and dumbly apply this rule to enough problems on my term exam to get a passing grade.

The problem isn’t just that I graduate with no real understanding of maths or economics. It’s that by trying to educate myself beyond the limits of my own cognitive capacity, my brain becomes trained to accept a dogmatic link between premise and conclusion. The only thing I have really learned from four (or nine!) years of this charade is that there exists this sacred black box in which intellectual ‘things’ happen, and that is not to be questioned. Forever after, because my status as an educated person depends on the sanctity of that black box, I become a militant defender of whatever it might output. In other words, I become a zealous believer in ‘The Science’. Follow it. Follow it right off a cliff.

I have also reduced my ability to create even those mindmaps that would otherwise be within my cognitive scope. University trains me not only to stupidly absorb the conclusions of others’ learning, but to deny myself the ability to engage in any of my own. I would be much better served by puzzling over how to put up fenceposts for free range chickens, at which I would succeed with my own two hands; rather than puzzling over, and ultimately failing, to understand fluid dynamics or molecular biology.

Then when a novel problem comes along, I am lost, for there is no equation for me to follow. Intellectually lost, I take to Twitter in a confused play for answers from the hashtags of authority I trust and identify with. How easy it becomes for they/them who wield these hashtags to guide me towards whatever dogma serves their/they’re interests. How stupidly will I cling to this dogma, with all the strength of my ‘education’. How heavily will I beat down dissent, with all the heft of my bourgeois status.

We need to stop educating people beyond their intellectual limits.