Divided we tweet

It seems that the public debate is divisive as never before. Left versus right. Social Justice Warriors (whatever they are) versus the alt-right (whatever that is). Admittedly, this impression may simply be a result of our unhealthy addiction to social media, which through its Algorithms of Hate and its cloak of anonymity tends to radicalise latent tendencies. It drives us into tunnels with those who share our vision, while at the same time shielding us from the consequences of our push-button outrage.

Nonetheless, I would contend that the fabric of culture is indeed in the process of tearing. The seams of our civilisation – things like basic human dignity, kindness, respect, humanity and tradition – now seem incapable of holding us together against the pressure of our outrage. The space for reasoned debate seems to shrink with every passing tweet.

A change is as good as the rest

The trouble is that the two sides are not even consistent in their own viewpoints. In the United States, the Democrats – formally defenders of the economically disadvantaged – have somehow come to represent an uneasy alliance between middle- and upperclass privileged ‘Coastals’ and traditional urban ethnic minorities, while the Republicans draw support from the equally awkward bedfellows of the superrich and the underclass of rusting, undereducated, mostly white ‘Heartlanders’. Neither side consistently upholds the values of the left (i.e. a larger state, more redistribution, protection of workers rights) or the right (more free market, less regulation, lower taxes and a smaller state). Members of a group which formally advocated liberal values such as free speech now rally behind brutal authoritarian slogans like “punch a Nazi”, failing to appreciate the irony of their own intolerance.

In Europe, mainstream social democrats increasingly resemble historical anachronisms, while the (Christian democrat) centre-right, desperate to hold on to a collapsing middle, is being overtaken by populists. The CDU in Germany has through the open borders refugee politics of Angela Merkel betrayed many of its own base, while the centre-left’s failure to check the consequences of rising inequality and globalisation constitutes an equal betrayal in the eyes of the old working class faithful. In Britain, the single-issue of Brexit has torn apart both the Conservatives and Labour. In its place, it has forged an unlikely anti-EU alliance between post-industrial working class northerners and well-off village conservationists in the affluent Home Counties which surround the (anti-Brexit) London metropolis. Only yesterday, Italy joined in the fun by voting in populists and extremists and booting out the moderate centre-left. But nothing illustrates the collapse of the old left-right dichotomy as forcefully as the 2017 French presidential election, which saw Emmanuel Macron’s virgin movement sweep aside both the PS and the Gaullists in his ascent to the Elysée throne, although the real victor was Madame l’Absention, followed closely by Madame Le Pen.

New times call for new political structures

The problem is, the model of the old left-right divide has always been missing something important. It was only ever the particular circumstances created by industrialisation which allowed for this one-dimensional approach to work as a good approximation. The left-right split also had the added advantage of convenience, in that the institutions of representative democracy work best when competition for political power is limited to a few, slightly differentiated brands. Being able to position two, three or four parties on a single spectrum reduced the task of political choice to something the masses could participate in without much active engagement or intelligence. The accidental balance created by industrialisation permitted us to overlook the fact that the model we were using to think about society was fundamentally flawed. As the world evolves, that balance is increasingly disturbed. We need to develop a new framework. As the world becomes more complex, so too much our political framework.

But how to adapt the model? Ideas abound; a popular version adds another ‘ecology’ dimension to the old left-right divide. However, in practice, environmentalism is less a coherent ideology and more a loosely grouped set of specific policy challenges. Once you break it down, the solutions to environmental problems can be tackled by taking a position on the conventional left-right spectrum. For instance, if you’re a left-winger, pollution taxes which internalise the externality seem like a good idea; if you’re a right-winger, you might like tradable pollution permits which achieve the same result. Nor does the environment feature particularly strongly in the ideological divide that is tearing the Western world apart at present.

The Social Triangle

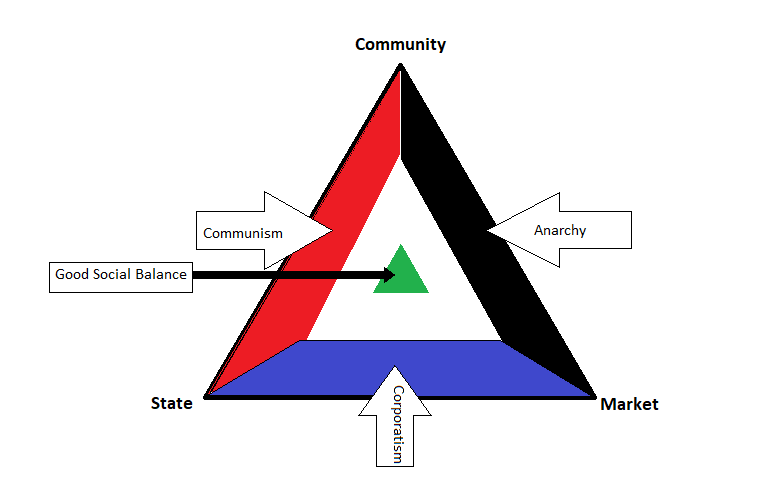

I propose instead a  model which takes into account the dimension I feel has been missing. As the diagramme illustrates, we can see society as consisting of three dimensions, the two which are conventionally understood in existing political analysis (the State and the market) and a third, that of community. Community can be understood as the voluntary organisation of people in groups without a specific transactional motivation (which is the market) and without the element of compulsion/threat of violence (which is the state). I argue that the absence of this dimension has, up to now, remained unobserved because we have in essence taken the role of community for granted. It is only as communities collapse – i.e. as society begins to drift ‘downwards’ towards the bottom side of the triangle – that we notice its absence. It is marked by a tendency towards the unholy alliance between the state and the market, in the form of corporatism.

model which takes into account the dimension I feel has been missing. As the diagramme illustrates, we can see society as consisting of three dimensions, the two which are conventionally understood in existing political analysis (the State and the market) and a third, that of community. Community can be understood as the voluntary organisation of people in groups without a specific transactional motivation (which is the market) and without the element of compulsion/threat of violence (which is the state). I argue that the absence of this dimension has, up to now, remained unobserved because we have in essence taken the role of community for granted. It is only as communities collapse – i.e. as society begins to drift ‘downwards’ towards the bottom side of the triangle – that we notice its absence. It is marked by a tendency towards the unholy alliance between the state and the market, in the form of corporatism.

Bowling alone

When looked at this way, society can be properly understood to be positioned somewhere within the above triangle. Societies that are more communistic can be placed within the red area of the triangle; those that are more anarchistic within the black area; and those that are more corporatist within the blue area. An ideally functioning society, like a three-legged table, balances all three dimensions and ends up somewhere in the green centre. Of course, in today’s world, we are observing a collapse of community – a massive drop-off in religious subscriptions, fewer bowling clubs, the death of the Boy Scouts, etc. and so we have drifted downwards, further towards corporatism. In such a world, the negative effects of the free market become more apparent as, for instance, the lack of community leads to an erosion of business ethics. But equally, a lack of community (for instance in the form of charities) heightens reliance on state-provided forms of welfare, revealing the innate corruption and incompetence of the state’s bureaucracy. Supporters of Donald Trump scream at supporters of Hillary Clinton and vice versa, but in the end, they are both suffering from the same affliction; a lack of community. The rise of populism is not a cry for more or less free market, nor is it a cry for a bigger or smaller role of the state. It is a cry for more community.

Which leads to the next question: What is leading to the erosion of community and how can we reverse this? That is perhaps the subject of another blogpost.