Dirty old classism

As I prepare to leave Dublin, I find myself reflecting on the things that make life in this city special. Many are splendid: the quick Dublin wit, the pleasant gift of the gab, the unique blend of international culture and local identity. But some are less worthy of celebration, and in this category I would place social class. I have travelled much in my life, and made it my business to understand a place as well as I could, but nowhere have I observed a social class structure quite like Dublin’s. For an issue that barely gets mentioned, class is everywhere on the streets of the Fair City. The fault lines are so visible that you can determine a Dubliner’s social class by their dress style, by their manner of walking, by the very first syllable of the first word that comes out of their mouths; even by the complexion of their skin. Not to mention the neighbourhood they live in: Even the city’s postcodes are euphemisms for the class of its residents.

By way of example: If you’re 25 and you grew up in Clontarf or Clonskeagh (postcodes 3 and 14, respectively), you went to college – probably either UCD or Trinity. If you grew up in Clonsilla or Clondalkin (15 and 22), you did not. The former ‘Clons’ are non-smokers, they support Leinster rugby, go on holidays to the South of France, shop in Dundrum or Powerscourt and work as accountants or barristers; while the latter Clons smoke, support Celtic or Manchester United soccer teams, go on holidays to Spain, shop in Blanchardstown or Liffey Valley and work as builders, shop assistants or else simply draw the dole.

Inequality of opportunity

That wouldn’t be so bad, if it were simply a case of hard work and merit allowing those who earned it to rise a little higher than others. But the truth is, your postcode has little to do with hard work and merit, and much more to do with who your parents were. You need only look at a Dublin child of 10 for a few short seconds and you will be able to project the course of their future prosperity, to a shocking degree. The ones with poor skin, screaming at the top of their lungs in public, and with their feet up on the opposing seat of the Luas Red Line train which they ride late at night without either a ticket or parental supervision, will not command decent salaries in 20 years’ time. The truth is, they have zero chance of advancing up the social hierarchy. Conversely the 10 year olds you meet in the Luas Green Line train, en route from their fee-paying private school in Milltown to their violin lessons in Ranelagh are almost certain to succeed, economically and socially. No matter how lazy they are in school or how badly the bow screeches across the strings, come 2036 they will probably be doing just fine.

Of course, I am deliberately picking extreme cases, in order to make my point. In reality there is a spectrum of privilege and disadvantage. Class is a fluid concept. But the observation is more than just anecdotal. A recent study shows that Ireland stands out among its European peers as having the highest intergenerational persistence of low educational attainment and the highest wage penalty for having a father with low educational attainment. In other words: if your dad didn’t finish secondary school, you won’t either. And you probably won’t earn very much money. This is a bit true everywhere, but it’s especially true in Ireland, and – though I haven’t got data – I’d be willing to bet it’s even more true in Dublin.

Does social class really matter?

I’ve sometimes been accused by those who know me well of over-focusing on this issue. After all, can’t we just let class be class? Some people read The Sun, others read The Guardian. Some people spend their leisure time in betting shops, others in art galleries. If that’s what makes people happy, why is it a big deal?

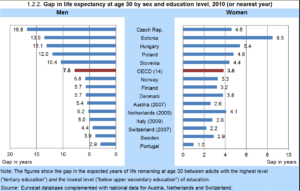

Unfortunately, class is more than just a preference in culture and clothing. It determines the quality and length of life, not only for yourself, but for your children and their children. The OECD indicator below shows this Class Mortality Gap in brutally stark terms:

While there is a wide variation across countries, what the chart reveals is that being middle class (i.e. you went to college) adds about 4 – 8 years to your life, depending on whether you are a man or a woman. This makes the Class Mortality Gap almost as bad as the Gender Mortality Gap. Having the misfortune to be born to socially disadvantaged parents is almost as bad for your health as being born with a penis.

De bleedin’ elephant in de roo-um

What makes the social class phenomenon in Dublin all the more eerie is the absence of meaningful discussion of it as an issue. The liberal commentariat are hardly silent on women’s rights, traveller’s rights, abortion rights, gay rights and just about any other social issue you can think of. Rightly so, you may well say. But on social class, their silence is deafening. It’s the last taboo subject in polite Irish politics. Worse: There’s a myth of classlessness in Irish society that seems to be perpetuated whenever you bring the subject up. Class, so the narrative often goes, is something that happens in England. And even then, the Irish of rank and privilege are most comfortable with it when it appears in BBC period dramas. Best to keep the Irish Sea and a hundred years of history between ourselves and the whole messy business!

Myself and my equally middle class partner recently went to see a show at a pop-up theatre in one of Dublin’s more middle class gated parks: Merrion Square. In the queue for pre-show food (wraps, don’t you know – one had one’s choice between halloumi and falafel) we conversed politely with our fellow show-goers, using rounded vowels and fully enunciated consonants. Then it was time to filter in to our seats. The show was called “Riot”, an eclectic mix of acrobatics, music and political commentary, featuring Ireland’s most famous drag queen, Panti, who since the Marriage Equality Referendum last year has become something of a national treasure. The politics played very much to the crowd. In between slapstick gymnastic routines and sing-songs, there were frequent called to “Abolish the 8th”, a reference to Ireland’s constitutional prohibition on abortion-on-demand.

But the showstopper was a young artist named Emmet Kirwan. He hails from a working class Dublin area known as Tallaght – a suburb built in the 1970s and 1980s to cope with the overflow from crowded inner city neighbourhoods. Kirwan’s unique blend of the Dublin working class vernacular and hip hop was as electrifying as anything I had seen on stage. With such an overtly political tone to the production, his indisputable talent and the obvious power of the medium to convey just such a message, this was surely the perfect opportunity for Kirwan to cast some home truths into the sea of class privilege upon which he gazed. I was waiting for the lyric: “A boy of three / undernourished and weak / Can’t afford to eat / Cause his ma’ don’t take home in a week / what youz are after spendin’ to sit in dah’ fuckin’ seat”

That lyric never came. Kirwan was happy to bang on about poverty, but he kept the teeth of social disadvantage well away from the manicured hands that were feeding him. The audience took it all in politely, letting out a dutiful cheer whenever the politics of the left-leaning middle class were voiced (pro-choice, anti-Catholic church) But nowhere was there an honest recognition of the dissonance between the culture on the stage which they were happy to expropriate, and the social reality of that culture’s roots, which they and their parents not only avoided at all costs, but in fact were the ultimate authors of.

Choose your parents carefully

If class is so present, such a problem, and yet Dubliners are so unwilling to talk about it, can anything be done? Is there anything more concrete we can offer to young people who’ve already made the mistake of not selecting rich parents before they were born? Or is it just too late? I, for one, think there’s quite a lot that could be done. We could start by looking at how (and in which neighbourhoods) social housing quotas are being filled; taking a hard and honest look at how the State is subsidising fee-paying private schools; looking at thresholds for inheritance and gift tax.

But before we get to concrete policies, the discussion has to start by acknowledging de bleedin’ elephant in de roo-um. Here’s my lyrical contribution:

Dublin is a class-riven city,

And the cost of that is shitty.

We bury are heads in de sand

Makin’ like it was all grand.

Wha’ a bleedin’ pity!